David Henry Hwang talks hate, sex, yellow face and faith

On a recent visit to Hong Kong, and nine months after he survived being stabbed in the head near his New York home, the award-winning American dramatist reflected on his life and work

ON A LATE NOVEMBER night in 2015, David Henry Hwang, the playwright probably best known for his 1988 Tony Award-winning M. Butterfly, nipped out to get some groceries. He and his family had just come back from a Thanksgiving trip and the fridge needed restocking. They live in Fort Greene, in the New York borough of Brooklyn. The neighbourhood has a website, fortgreenefocus.com, and if you search it you can find a closed-circuit television photo taken that evening a few seconds before what happened at about 9pm.

The setting: a street corner by a leafy park. Enter two men. One, slightly hunched, is carrying a white shopping bag in his right hand: that’s Hwang. The other is younger, taller, wearing shorts and a backpack: that’s the man who stabbed him in the head.

In the ensuing scene, immediate dialogue is confined to a yelled expletive from Hwang. The young man exits at speed, not pursued by Hwang, who decides to keep heading for home. Considerable loss of blood makes him wobbly: he sidles into a wall and a parked car. Still, he’s remarkably clear-headed. He leaves the shopping inside his front door, calls out to his family that he’s been attacked and continues tottering on, to the hospital. (In the piece he wrote about it for The New York Times in January he concedes, “I realise that dropping off the groceries was a bit over the top.”)

His daughter, Eva, 15, and his wife, Kathryn Layng, run after him. Layng, the actress who played Nurse Mary Margaret “Curly” Spaulding in Doogie Howser, MD, calls out to medical staff at the hospital entrance. They take him into the building. A real-life medical drama ensues.

Hwang, 58, was lucky to survive. His vertebral artery had been severed, and the injury was so close to the skull he had to be taken by ambulance to another hospital for surgery. The police came to interview him several times but his assailant has never been caught. In the Times article, he speculates about hate crime. He mentions a 16-year-old Chinese exchange student, slashed in the face on her way to school in Queens two weeks after his attack. He has learned, he writes, that “Asians are seen as easy targets because of perceived language barriers and a reluctance to report crimes”.

Eight months on, does he still think it might have been a hate crime?

“I don’t feel there’s a whole lot of evidence towards that,” he says, calmly, in a room at the Asia Society. He’s in Hong Kong to take part in one of the society’s “evening conversations” the following night. It will be moderated by Ken Smith, Asian-performing-arts critic for the Financial Times, who’s also in the room, along with two Asia Society staff members.

In May, it transpired that the 16-year-old Chinese student who’d been attacked was wrongly targeted: another Chinese girl, aged 14, who’d been involved in an affairwith a man, was the intended victim.

“Two guys were indicted, one was Chinese, one was white,” Hwang says. Which one had the girl had the affair with? “I didn’t follow which was which.” (According to The New York Times, both men have been charged with assault but one of them, Wilson Lai, has been additionally charged with rape and criminal sexual acts.)

Given the context, it’s odd that Hwang didn’t make the distinction between the two.

“I guess it’s a little strange,” he agrees, smiling. “The affair, the underage sex, the wrong person slashed – that’s the interesting part of the story to me.”

You can see why it would appeal, and not just because Hwang is currently writing and producing episodes for television series The Affair. He’s made a brilliant career out of shifting perceptions. Now his own take on an event, as set out in The New York Times, has already taken on a separate life, requiring mental revision, reassessment. He wrote that initial account a couple of weeks after the attack; but, as he says several times, he’s not yet finished with this personal episode.

When asked to show the scar, he readily turns his head and pushes his left ear lobe forward to expose a red weal, about 5cm long – “very subtle”, as he says, although that vulnerable location between cranium and flesh is enough to make the onlooker wince. He was extraordinarily lucky. Even before the victim was identified, fortgreenefocus.com had run a story (“Blood-Stained Sidewalk At South Portland and Lafayette Startles Residents”) tracing the mysterious gory splatters all the way to the hospital.

“I don’t feel particularly traumatised,” he says. “It’s a little weird. In another six months? Maybe.”

This is the second time we’ve met. The first was in December 1997, in Singapore. Hwang’s play Golden Child was due to open there, at the Victoria Theatre, in early January and then transfer to Broadway; it was the first time in Broadway’s theatre history that a play, complete with its Broadway cast, was making its international debut at an Asian venue before heading for New York.

Hwang had flown in from New York for 24 hours to attend a press conference and do a few interviews. He’d arrived at 2am. He’d then sat, jet-lagged, in his hotel room rewriting some of the script.

“I’ve never gone through a process this long on a play,” he’d said at the time. “I still feel there’s work to be done.”

Reminded of this scenario 19 years later, Hwang, who’s still in possession of a lively thicket of now-greying hair, raises his eyebrows in polite doubt. “That seems intense, even for me,” he says. And yet, after Golden Child’s 1998 opening night his itch to keep working on it evidently wasn’t quelled. The play – based on the life of his maternal great-grandfather, who had three wives, a situation that became problematic when he converted to fundamentalist Christianity – is book-ended by a narrator. Hwang wasn’t happy with that framing sequence. When New York’s Signature Theatre held a season of his works in 2012, he revised both beginning and end.

Something else altered in the intervening years. In the 1950s, when his mother, Dorothy, relocated to San Francisco from the Philippines (where her family had moved to from Amoy, now Xiamen), she’d met his father, Henry, originally from Shanghai. Before a marriage could take place, Henry had to convert to Christianity, and their three children were raised in a strongly religious environment. Or as Hwang has put it, “I grew up with a lot of pastors.”

At 19, as a student at Stanford University, he’d rejected these beliefs. In Singapore, he’d said how being an ex-fundamentalist was like being an ex-Catholic (“You think you’re going to hell”) and he’d recalled how his mother had then taken him to a faith healer. “He said, ‘Do you think this has anything to do with sex?’ and I thought, ‘That’s the least of it.’ Then later on, someone said to me that all my plays have this kinky sex in them and my answer was, ‘You can define a lot of things through sex.’ So maybe the faith healer was right.”

It was therefore rather a surprise, when preparing for this interview, to find an eight-minute clip of Hwang on YouTube discussing, with an earnestly probing young woman (“Did you feel you were missing some of the grace and mercy?”) his return to Christianity. Once again, he looks a little startled at the reference; he eventually dates it to the summer of 2011, when his play Chinglish, a comedy based on Sino-American misunderstandings, was being premiered in Chicago.

“Let me put it in this context,” he says. “The faith healer happened when I was 21. By the time I was in Chicago, I’d worked through a lot of anger about religion.”

I’m comfortable with mainstream denominations – for example, the Episcopalians. But I can’t say I’m religiously observant.

The process had begun with Eva’s enrolment at a Brooklyn pre-school that was connected to a church. Kathryn and he had liked the pastor. “

“I’m comfortable with mainstream denominations – for example, the Episcopalians,” he says. “But I can’t say I’m religiously observant.”

At which point, Smith (who is formidably well connected, organised Hwang’s first professional trip to China in 2005, from which the seeds of Chinglish sprouted, and, with his wife, Joanna Lee, has been involved in China-related Hwang projects ever since) makes an interjection: “But you did go to church in Chicago, a Lutheran one.”

Hwang pauses for a perfectly timed millisecond, looks round at Smith with an Et-tu-Brute? grin, and turns back. Yes, he concedes, he did indeed attend a Lutheran church: the pastor was a supporter of his plays so he went along. And yes, these days he no longer carries the hostility that, for example, characterised such early works as Family Devotions (1981) and Rich Relations (1986), which was “not a very good play”.

Chinglish, incidentally, was also much revised. (Of the early drafts, Smith remarks in an e-mail, “For someone who barely speaks the language, DHH was brilliantly insightful of the greater dynamics involved but his details were quite sketchy.”) After it travelled on to Broadway in 2011, and was nominated for three Drama Desk Awards, Hwang rewrote the ending for a 2015 production in Los Angeles. He wanted to reflect the complex shift in US-China relations in the intervening four years. As Tim Dang, the artistic director of that production, observed, “It is rare that any changes are made after a play has received a Broadway run and has been published.”

Such tweaking and shape-shifting suggests a restless perfectionism; also, perhaps, a desire to be all things to all people. Episode nine of The Affair’s second season told the story from four points of view; it seems appropriate that Hwang wrote two of them.

“It’s a show about a Rashomon [multi-perspective] way of looking at the world, and that suits my sensibility well,” he says. “I do tend to be a bit of a pleaser. I’m trying to work on being less of one.”

Why? “As an artist it’s important to have a point of view. But theatre and television, being collaborative arts, mean that flexibility and a willingness to take input are important. However ... it’s all very well to listen. But most of the time it’s not that helpful. It’s important not to take people’s advice.”

Why now? “It’s a part of growing up.”

He once told an interviewer, in 1988, that aesthetic criticism is “nothing compared with being told that you’ve set the Asian-American back 10 years”. When I read this out to him, he says, “Twenty, actually. I think I said it was 20 years.” (It was 10 but maybe the intervening years have lengthened the impact.) Asian-Americans, he says, wanted the work to speak of their own experience. “And it’s not possible because these communities are heterogeneous.”

It’s all very well to listen. But most of the time it’s not that helpful. It’s important not to take people’s advice

Naturally, his own experience was particular: he didn’t speak Chinese at home, Chinese culture wasn’t celebrated (he didn’t, for instance, know the dates of lunar new years) and his father was a larger-than-life character who founded a bank called Far East National but fixed his gaze firmly westward. When Hwang wrote his first play, FOB, which premiered in 1980, and Joseph Papp, the great American theatrical producer and director, had dinner with his parents in Los Angeles, Henry Hwang chose a French restaurant.

“There was the son holding on to tradition and the father very westernised,” Papp said later. “David was looking for his past.”

The initials FOB stand for “fresh off the boat”; the play was about a cultural stand-off with three, earlier established letters of the alphabet – ABC, or American-born Chinese. When it was originally performed in Hwang’s Stanford dorm, his parents came and Henry Hwang, who’d been perplexed by his son’s literary ambition, was moved to tears. David, however, wanted to step out publicly on his own. For his next play, he edited his own name, dropping the “Henry” part – a gesture his fellow dramatist Sophocles, author of Oedipus Rex, might have understood. The new work was Rich Relations. It was clearly based on his family, except the characters weren’t Asian. After it flopped, he re-revised his name.

These days, the term fresh off the boat – clearly spelt out, no relation to FOB – refers to a successful American television comedy series, spun off from chef Eddie Huang’s memoir. It’s the first Asian-American sitcom in the US since Margaret Cho’s generally panned 1994 series All-American Girl.

“I like Fresh Off the Boat, I liked the book and I like Eddie Huang, who’s denounced the show,” Hwang says. (Huang has made it abundantly clear he feels the show doesn’t reflect the memoir.)

Hwang, by contrast, has been looking into the sacred depths of Qing Chinese literature. He’s just co-written – with composer Bright Sheng – the libretto for Dream of the Red Chamber, which will premiere at San Francisco Opera in September. When Sheng initially asked him to do it, he’d refused. “But Bright’s will is stronger than mine because he grew up during the Cultural Revolution and I only grew up in LA.”

As Hwang can’t read Chinese, he had to work from an English version. The book is famously dense – twice the length of War and Peace with at least 500 characters. What did he make of it?

“I assume it loses something in translation,” he says, with another grin.

The droll Smith can be heard remarking there are those who think it loses something in the original. The conversation, briefly, moves on to Chinese erotica. Smith describes the plot of the Qing work, The Carnal Prayer Mat, which involves an interspecies penile transplant and inspired the 1991 Hong Kong film Sex and Zen. Hwang, as that faith healer of almost 40 years ago might have been gratified to see, is gripped.

“You could do that in China?”

He has written libretti before, including those for Elton John and Tim Rice’s Aida and Disney’s Tarzan. In the end, he enjoyed distilling the Dream down to a slender two acts and eight characters. Thoroughly editing a work, after all, is what he loves. “But with opera I wish there were more opportunities to rewrite once you get into rehearsal. If you do a Broadway show, a big Disney one, you have four weeks, with eight shows a week, before opening. In a play, there’s less money, so less time, but it’s still seven to 10 days before opening. In opera, there aren’t that many performances to begin with.”

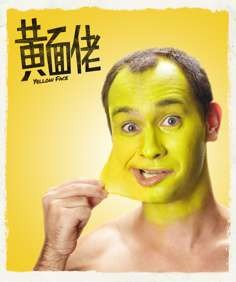

For years, he’s been involved with The Lark, which describes itself as a “theatre laboratory” in New York. He used the facilities there while developing Yellow Face (2007) and Chinglish. In 2013, he partnered with The Lark again to develop a Playwright Exchange & Translation Residency programme that hosted four Chinese writers, including Hong Kong’s Candace Chong Mui-ngam; their work was performed at the Signature Theatre. He’s hoping that a reciprocal event with young American playwrights in China can soon be arranged.

“I’m a theatre person and this is the way the theatre can increase understanding between the US and China,” he says.

At this point, Kathryn, Eva and his son, Noah, 20, enter the room and wait, pleasantly, in the wings. The Hwang family is planning to fly to Japan after the Asia Society event; taking a proper holiday is a direct result of the stabbing incident. He’s now working (he says) at being better at vacations. At the following evening’s talk, he’ll be good-tempered, generous and, apparently, relaxed; the only trauma he’ll refer to is the fact that his dog once bit the Asia Society’s Hong Kong executive director, Alice Mong.

Would he be pleased if his children became playwrights?

“Yeah, if they wanted,” he says. “I’ve managed quite a nice life from it.”

As it turns out, however, Noah is into football.

“Placekicker,” pronounces his father, genially. “That’s a surprise. I feel like we come from a long line of men who don’t do what their fathers want them to do.” ■