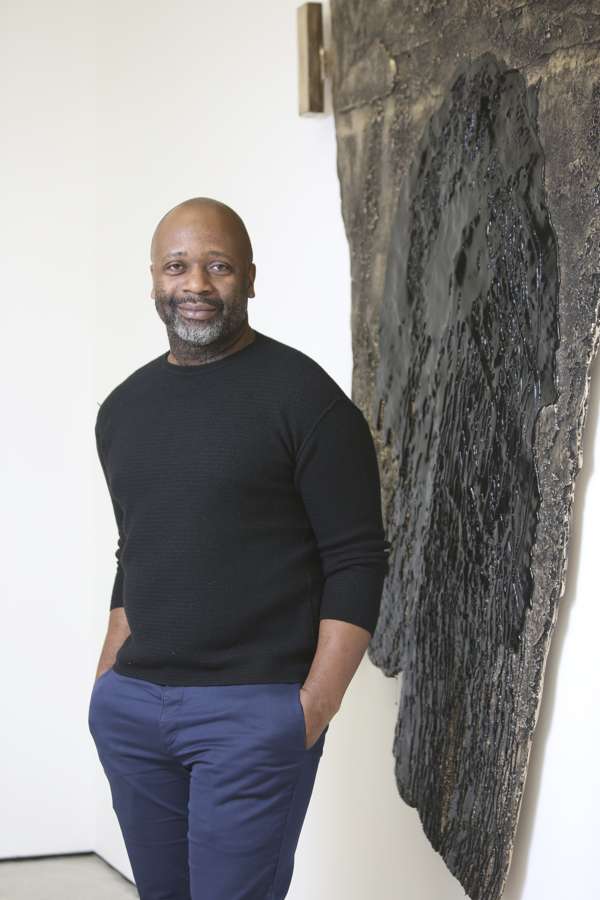

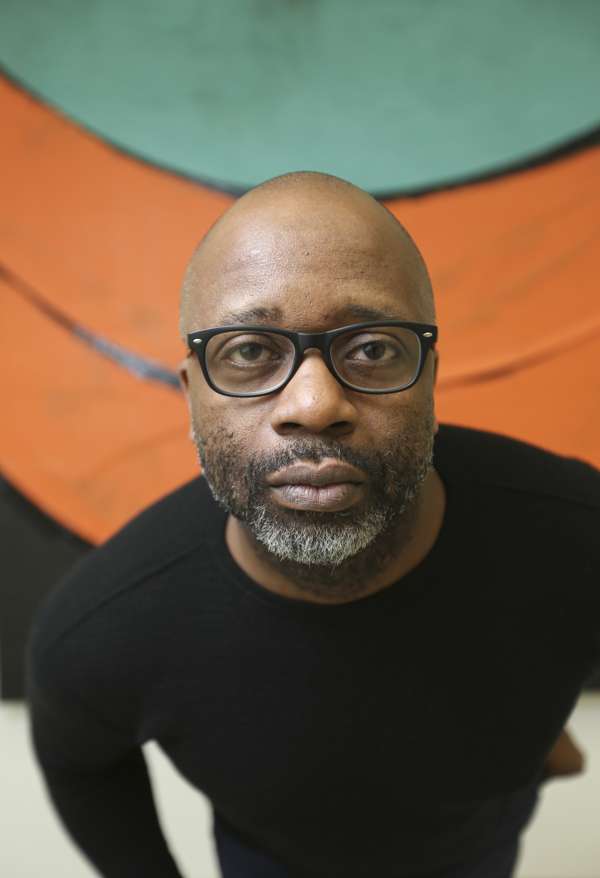

Theaster Gates, artist who’s doing it for himself – or is he?

The American, in Hong Kong for his second exhibition, sees hope in his latest work, but ‘not the world’s hope’; making art ‘is a selfish act’, he says. Yet in Chicago he’s opened, at his expense, a ‘repository for black American culture’

If you visit Theaster Gates’ new show, which opened on Tuesday at Hong Kong’s White Cube gallery, you’ll see a large work hanging opposite the Connaught Road entrance. It’s made of bronze. The top half has a muted golden sheen but the bottom half has been so thickly covered with tar, it’s as if it’s been glazed, and therefore it has its own – separate – reflective quality. You’ll probably think (because the outline seems convincingly approximate, right down to Florida’s panhandle), “That is a map of divided America, 2017”.

The resemblance, however, is a coincidence. “No,” states Gates, flatly, in one of White Cube’s back rooms when I ask if he’d planned it. “It’s a section of a roof.”

It’s the Saturday before the show opens and labourers are still hanging works; a forklift truck downstairs testifies to the weight – literal, if not metaphoric – of that bronze, one of three in the exhibition.

The fragments came from a Catholic church called St Laurence, which was demolished in 2014. It was in Chicago, where Gates, 43, grew up and where his father tarred roofs for a living, with occasional help from his only son (one of nine children). By casting discarded pieces in bronze, Gates Jnr has preserved them as artwork; he’s made something lasting out of obliterated, anonymous labour.

At the edges, he’s deliberately retained the supports that were part of “the gating system”, the technical term for a structure that controls the passage of molten metal into a mould. The pun on his own name would seem to be another coincidence; the point is that unseen toil should be made visual.

The show’s title is “Tarry Skies and Psalms for Now”.

“I wanted the show to deal with something both abstract and representational,” he says.

When I remark that the term “tarry skies” seems a deliberate echo of Starry, Starry Night (singer Don McLean’s 1971 homage to Vincent van Gogh), Gates nods, cleaning his glasses thoughtfully. After a while he says, “The tar work has been a kind of conceptual work, equating vernacular labour with high art. I wanted to move past that and let the tar be art, be itself, be part of artistic vocabulary.”

Unprompted, he starts to mention his hopes. Thanks to Shepard Fairey’s poster, the very word Hope – especially in the context of a socially engaged black artist based in South Side Chicago – inevitably brings to mind the rise of the young senator for Illinois who became US president, whose presidential library (Gates was on the advisory panel to choose the architects) will be about 10 blocks from where the church of St Laurence once stood, and who’s now gone. But Gates doesn’t want to talk global politics or assess Barack Obama’s hopey-changey thing.

“I think the show is about the hope I have in my art,” he says. “It’s not a grand gesture of hope. It’s the hope that needs to live in a private place, that’s private and personal, that compels a person to continue to take action. It’s not the world’s hope.”

For a while he sits in silence, contemplating the books on the White Cube shelves. When I eventually ask about the weighty burden of expectation created around him, he replies, politely, “I’ll answer questions about art but I’m going to resist any grand leaps. The show is about painting, and painting requires hope.”

This is our second interview. The first, in September 2013, was also at White Cube Hong Kong, where he was opening a show called “My Back, My Wheel and My Will” that was simultaneously running at White Cube Sao Paulo. Then, I hadn’t heard of him. Although he’d entered ArtReview’s Power 100 list the previous year at No 56, he wasn’t widely known outside the United States but he was certainly on the move. A month afterwards, in October 2013, the next ArtReview Power 100 list came out and he’d ascended to No 40. (He’s currently at No 16, six places below Ai Weiwei and 14 places above Jeff Koons.)

I’m really stepping away from this idea there’s something I can do for others. It’s just not true. I can make a platform because I want to make a platform and it can make space for others if they choose but ... Making art is a selfish act

Gates didn’t have the usual artist’s CV – his background was in urban planning and he spent five years overseeing art installations for the Chicago Transit Authority. He’d then been employed as an arts administrator by the University of Chicago and, in 2006, he bought a former sweet shop so he could live in Dorchester Avenue, an area that was dodgy but cheap and close to the university. A couple of years later, after the financial crash, he bought the place next door for US$16,000.

That was the beginning of the Dorchester Projects; the title cleverly suggested both a community aspect (“projects” being the American term for “public housing estates”) and an ongoing artistic endeavour. Since then, he’s bought other vacant buildings, had them renovated and created cultural centres – and work – in a neighbourhood where half the residents live below the poverty line. In artspeak, the buildings were “found objects”.

He’d had two other standout moments. One was his first show, in 2007, called – he’s good with titles – “Plate Convergence”. Gates, who studied ceramics as a student, spent four months in Tokoname, Japan, working as a potter. The exhibition was supposed to be the work of a man, Shoji Yamaguchi, with a vivid back story (Hiroshima survivor, husband of Mississippi black activist, leader of commune, killed in car crash). His son attended the opening, and Gates served “Japanese soul food” on the crafted dishes.

Not a word of this was true. There was no Yamaguchi and the “son” was an actor. Gates had created a risky collision, and his fledgling career could well have imploded, but he’d read his audience well: people loved the work, then they loved the deception. What I particularly liked about the tale was that the clue it might be theatre was already hidden in his name. (And a man called Gates, who’s made a career out of access to buildings, is surely exhibiting a form of what psychologists like to call nominative determinism.)

The other memorable work was “12 Ballads for Huguenot House”, which he’d shown at Documenta – the art show that takes place every five years in Kassel, Germany – in 2012. He’d removed the decayed innards from a house on Dorchester Avenue, across the street from where he lived, and transplanted them into a derelict house in Kassel that had once belonged to a Huguenot family – Protestant refugees from Catholic France. He’d said he wanted to “conflate a German past with a black present”.

The demolition crew in Dorchester Avenue had been Hispanic and some of Gates’ neighbours had wondered aloud why he didn’t use black workers. Gates is a pragmatist – the Hispanic crew had the proper equipment and permits – but he asked them to train some locals; and so five men, recently released from prison, helped to dismantle the house while saving its vital trimmings, its wood, its flooring, its windows. The project became a double rescue, of people and place.

The Documenta catalogue included a sort of thought diary Gates kept while he was doing the installation in Kassel. He was brought up in the strict Baptist tradition and, when he chooses, he can write, speak and sing in the thrilling cadences of a preacher who listens to Kanye through his headphones: “This building deserves to re-live, to have the power of resurrection move through its beams and belly and mortared joints [...] This is no longer a joke or a question. This project must feed me and others; it is no longer just an artistic gesture [...] My spirit is no longer my own [...] This building is our great hope. It is everlasting and fleeting [...]”

After that, he seemed to pop up everywhere, with long profiles in prestigious publications. When we met in 2013, he’d just bought the Stony Island Trust & Savings Bank building, erected in 1923, from the City of Chicago for US$1. He’d been assisted in this transaction by the mayor (and Obama’s former chief of staff) Rahm Emanuel; the deal was to create something that would benefit the community, using money from loans, the sale of Gates’ art and fund-raising.

Sometimes being an artist is not about making art, it’s the ability to know when art is happening

The Stony Island Arts Bank opened in October 2015. He has described it as a repository for African-American culture; among other things, it has 4,000 objects of “negrobilia” – i.e. vintage racist objects. As of last autumn, it also has the Cleveland park gazebo in which Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old black boy, was shot dead by police in November 2014. The boy’s mother, Samaria Rice, signed an agreement with Gates to lend it to him for a future exhibition.

“When I asked her if there was anything I could do to help remember Tamir,” he says, in White Cube’s back room, “she actually had an entire exhibition already in her head. ‘I want this to happen like this, I want his life to be talked about.’ Sometimes being an artist is not about making art, it’s the ability to know when art is happening.”

The Arts Bank also has the archive of Ebony magazine, founded in 1945 for an African-American readership. Some of those magazines – placed in a library like a round tower – feature in his new show that opened this month at the National Gallery of Art, in Washington. The exhibition is called “The Minor Arts”, but Gates is no longer a minor artist.

There’s always been a sense of spiritual heritage in what Gates does. (“Theaster”, which is also his father’s name, means “star of God”.) Some of the hard-working St Laurence wreckage – bell, roof tiles, statue – featured in “Gone Are the Days of Shelter and Martyr” at the 2015 Venice Biennale. That exhibit also included a video of Gates singing with his music ensemble, The Black Monks of Mississippi.

In 2014, his first public commission in Britain, Sanctum, was set within the ruins of a Bristol church; a space was created, also out of salvaged material, where a public performance lasted 24 hours a day for 24 days and nights.

As the second half of the White Cube show’s title – “Psalms for Now” – hints at current need, I’m curious about how that spiritual happening might resonate these days.

“Oh man,” sighs Gates. He’s taping the interview, which suggests a rather less blithe attitude to the media than last time. “Yeah.” After some thought, he says, “Antonio Negri talks about beauty being born out of a kind of multitude – a by-product of collective will. I didn’t do anything in Bristol. Bristol did Bristol.” (I had to look up Negri afterwards; Wikipedia describes him as “an Italian Marxist sociologist and political philosopher”.)

“I’m really stepping away from this idea there’s something I can do for others,” Gates says. “It’s just not true. I can make a platform because I want to make a platform and it can make space for others if they choose but ... Making art is a selfish act.”

Well, I say, art also gives.

“It gives,” he agrees. “But it has to be born inside a person, a will, an ego ... hopefully it goes from me to we really fast. But it has to start with an individual goal, an individual hope – a desire to see colour in darkness.” He must like this line because he says it again to himself, very quietly, “The ability to see colour in darkness.”

“You know, if we’re talking about a conservative right and the Trump presidency, those things only change life for the already upwardly mobile, the already aspiring middle class. Many of the challenges poor people faced, they’ve faced in the last 70, 80 years ... It’s probably those at the very bottom who’ve needed to see colour. It is the survival mechanism.”

In a press release about the White Cube show, he asks a question: “Could what my dad taught me trump established artistic practices?” When I first read that, I thought there might be some underlying wordplay but when I recite it back to him and ask what the answer is, there’s a longish interval and then he says, “Yes. What he trained me to do is as legitimate as anything else I’ve ever learned.”

In this exhibition, along with the bronzes, Gates is using roofing tar to paint on a canvas of Naugahyde, a synthetic leather. The Naugahyde came as a job lot with an upholstery shop he purchased; after a year of sitting with it unused, he recognised its potential. It’s clearly a more personal form of art. These new works are big (that forklift truck) but they’re still inside the gallery. Now, you feel, he’s looking at his own life, not necessarily the nation’s.

“I like that the material is a signifier of a particular time, like my mom replacing her own seat covers in the kitchen. It functions as a baton from the past to the present. It would have been in my dad’s Chevrolet Caprice 83.”

His father, he says, worries about him: “He wants me to sleep more and go to church.”

What does he want?

“I’m happy,” he says, solemnly. After a pause he adds, “But I’m not content.” (His crossed feet are waggling under the table.) Asked what would make him content, he says, “I want to understand more about the material and immaterial world. We understand the eternal through things on Earth. And we understand people on Earth through emotion and empathy, invisible things. Those things matter more and more to me.”

Is that age?

“No. It’s time.”

Roofing has put painting into his head; and painting has given him the desire for more quiet time, especially to read. At the moment, he’s working his way through M.M. Bakhtin’s The Dialogic Imagination (1975; “It’s essays on the idea of time in literature”) and researching Minotaure, a Surrealist journal, edited by André Breton, that was published in Paris between 1933 and 1939. Minotaurs are much on his mind as he prepares for an exhibition at the Kunstmuseum, in Basel, Switzerland, next summer.

“I’m thinking of the beast as a metaphor for the perversions that grow when God and man fail to keep their contract – the monstrosities that are born or that show themselves. I’m also thinking about the prison-industrial complex in the United States.”

Why?

“Because a lot of black men are in jail, and I think in some ways jail functions as a labyrinth. People say they’d rather be inside, that the rest of the world no longer makes sense. With the minotaur, you imprison him or you slay him. There is no empathy with the beast.”

He says he’s been thinking about this for four years. When I tell him that he doesn’t seem quite as happy as he was four years ago, he gives a sudden, transforming grin. Within a few minutes, he’ll be theatrically mugging for the photographer, singing snatches of Sting (“Roxanne! You don’t have to put on the red light ...” ), discussing last night’s foot massage, planning a tailor’s fitting. Just for these last few seconds, however, on the threshold, he’s still in serious interview mode.

“This is not my jovial self. These conversations really matter. I don’t feel happy – I feel clear.”

“Tarry Skies and Psalms for Now” continues at White Cube, 50 Connaught Road Central, until May 20.