Life in a Chinese treaty port: Eurasian traces great-grandparents’ journey from London slum to Hong Kong and beyond

Ian Gill hadn’t even heard of Chefoo (now Yantai) until he started tracing his family’s roots and found out his great-grandparents had lived an enviable life there in the 19th century

My wife and I travelled to Yantai, formerly known as Chefoo, in October, to explore a family mystery. We had asked a local historian if we could meet him, but had no idea what to expect. To our surprise, our four-day visit to Shandong province turned out to be revelatory, attitude-changing and deeply moving.

A few months earlier, I must confess, I had not heard of Chefoo. Then I made the astonishing discovery that my English great-grandparents had moved from Hong Kong to northern China in 1873, during a period when many Chinese were flocking south to the fledgling British colony. Following the Treaty of Tientsin (1858), Chefoo had opened as a treaty port in 1861, presenting opportunities for the intrepid. But my forebears were neither colonial administrators, nor merchants, nor missionaries. They had no organisation to bail them out if things went wrong. So why had they risked their future, and that of their children, with such a move?

An investigation of this historical puzzle led to encounters as enthralling as the stories of Edward and Mary Ann Newman that would slowly emerge. It included finding two elderly cousins with whom I shared great-grandparents and meeting them on opposite sides of the world.

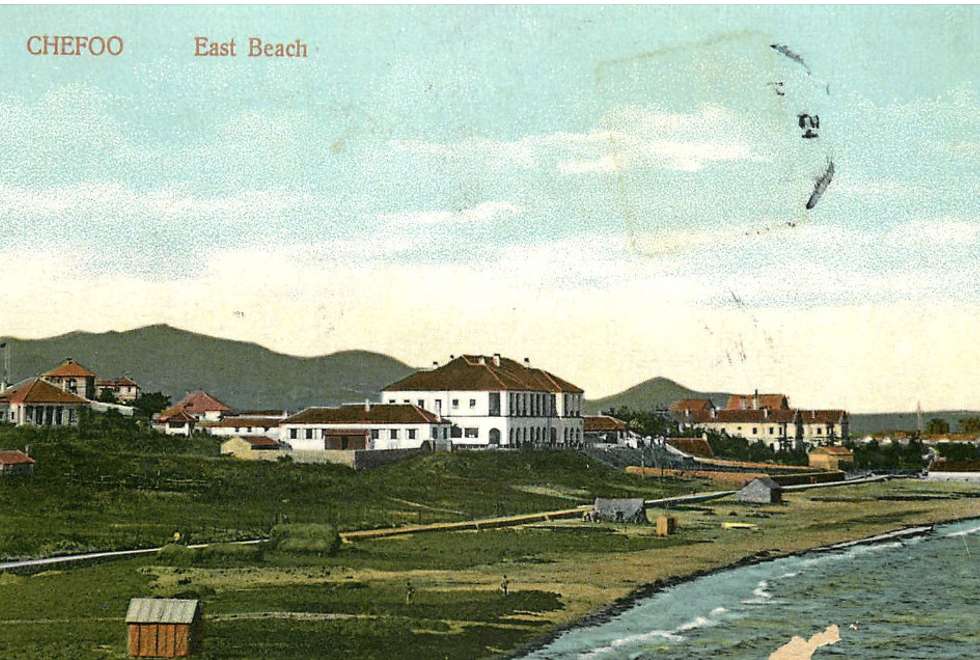

During our taxi ride from Yantai airport, it was hard to imagine that the bustling, modern city of seven million that unfolded before us could have grown out of the walled town of 10,000, plus a few dozen foreign residents, that had greeted the Newmans a century and a half earlier. But, when we alighted in the seaside district of Chefoo (Chifu), we found ourselves in the old foreign quarter, where many colonial-era buildings have been preserved or restored.

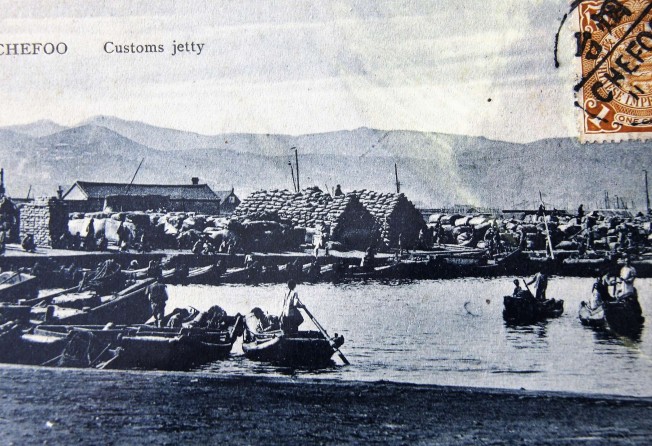

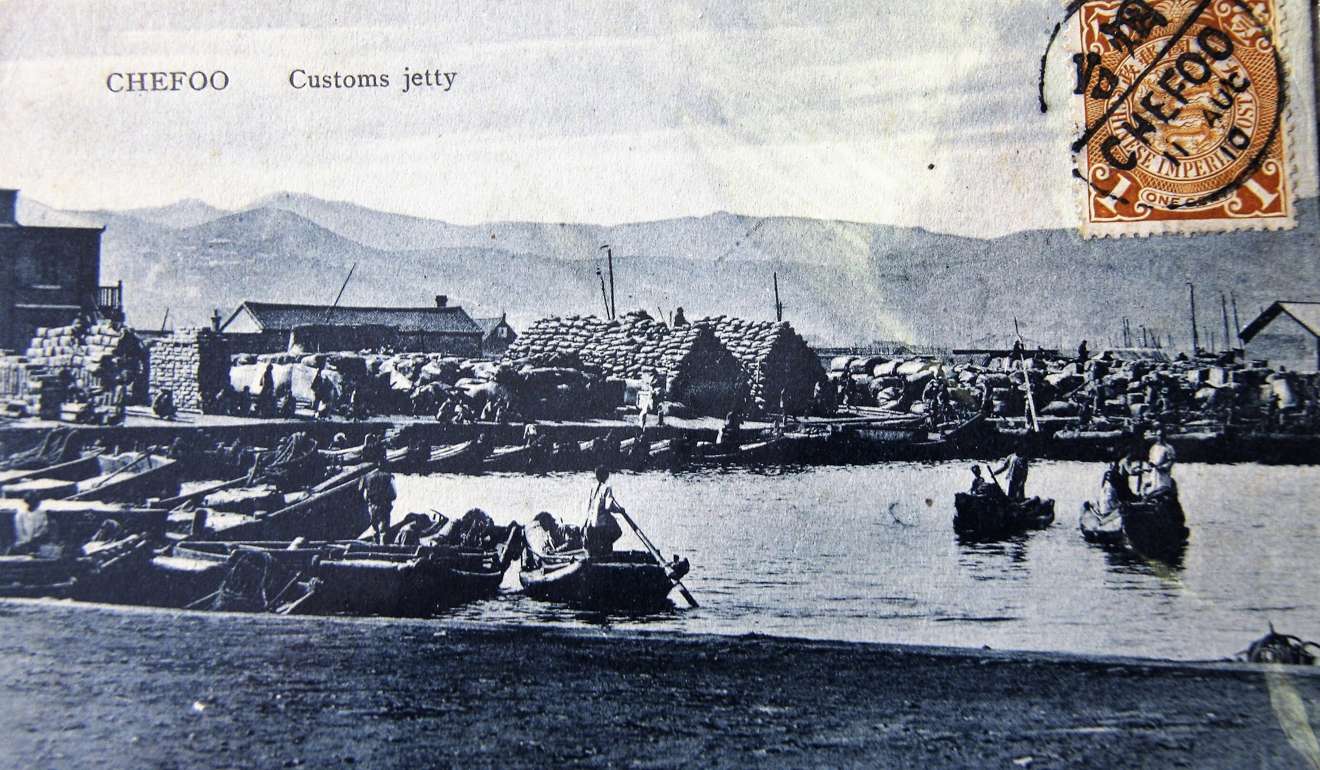

Black-and-white photographs of the former settlement lined the walls of our hotel, which stood on the site of a former French convent. That evening, we met Victor Wei Chunyang, a tall, dark-haired Yantai historian. He took us to the greystone customs house, with a roof of curving tiles, and the wharf where the Newmans had disembarked from a lighter after a three-day journey by steamer from Hong Kong. We supped at the former premises of a British merchant on the old Beach Road the Newmans would have taken, their wooden trunks borne by pigtailed coolies.

From the still-existing Chefoo Club on the seafront, we gazed at the same long, curving bay the Newmans had seen, only in their day there would not have been tall buildings standing back from the sea, but bare fields undulating towards shallow hills. On the distant shoreline, they would have seen a white speck – the single-storey structure that was to be their home. Holding back her dark hair against the sea breeze, Mary Ann must have wondered how she would bring up her infants in such a hinterland.

My mother had tried hard to learn about her father’s parents, but had met only heartbreaking frustration. Through American descendants of her father’s younger sister, Aunt Ellen, she had heard various stories: that Edward hailed from Ireland, that he and Mary Ann had joined the London-based China Inland Mission; that they had later owned the Astor Hotel in Shanghai.

Alas, like Chinese whispers, each of these tales turned to be distorted echoes of the truth. When Mum died in 2006, she knew little about the grandparents who had helped to shape her fate.

By the time I took up her search a decade later, the internet had radically changed research, bringing hitherto unknown archives to the computer screen and historians, researchers and librarians within easy reach.

Henry Ching, son of former South China Morning Post editor Harry Ching, tipped me off about Carl Thurman Smith, who provided my first big break. Smith was an overweight, obsessive American missionary who, in the decades until his death, in 2008, haunted Hong Kong libraries and records offices, unearthing personal details about the colony’s early residents and typing them up on tens of thousands of file cards.

“He lived in this flat in Mei Foo [housing estate] and his walls were lined with filing drawers,” recalls Vaudine England, a Hong Kong journalist and historian for whom Smith was a family friend through her father, also a churchman. “He was a bit of a social recluse but to me he was adorable,” she says.

What made Smith different was that he focused on ordinary people, of all races, not just British governors, officials and businessmen, as earlier historians had done.

“He was the father of modern Hong Kong history,” says England.

Smith’s 140,000 cards are kept in the Public Records Office of Hong Kong and, when I saw his cards on Edward Newman, I knew I was getting the first solid information about him. In 19 lines, packed with abbreviations, Smith presented a snapshot of Edward from the time he married Mary Ann Sait at St John’s Cathedral, in Central, on March 18, 1869. The cards also recorded his career along with details of their children. When daughter Anne Elizabeth Victoria was born, on September 29, 1870, for example, Edward was a steward with the prestigious Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) and living at 11 Old Bailey Road. When his son, Frank, arrived, on January 30, 1873, Edward had become a clerk with P&O. Later that year, when he was put on a jury list, he had been promoted to the position of assistant.

The cards include two more entries, decades apart. On January 1, 1863, Edward was administrative partner with Margesson & Co, a trading company founded by Henry Margesson, a long-standing resident of Macau. The other item was the stunner: on January 3, 1893, the Family Hotel in Chefoo was offered for sale as part of the estate of Edward Newman. Chefoo? While researching the place, I contacted Hong Kong-based historian Robert Nield, author of two books on the treaty ports. He and his friend Nicholas Kitto, a photographer, had been to Chefoo many times and sent me an abundance of materials. But it was one startling question Nield posed that changed everything.

A resurgence of historical interest, among the Chinese as well as Westerners, has led to changing attitudes towards the colonial era

“Do you know Duncan Clark?” he asked. “He is the grandson of another Duncan Clark who was a tidewaiter with the Customs in Chefoo.”

I recalled my mother telling me that her aunt Annie, her father’s elder sister, had married a Duncan Clark. A few weeks later, I was sitting in the living room of my new-found cousin in Coventry, England. An octogenarian in robust health as well as a meticulous family historian, the younger Duncan Clark gave me family photographs and related anecdotes handed down from his father. He also told me that Edward had married the widow of a close friend, Edwin Sait.

An online search unearthed strong links between Edward, Edwin and Mary Ann. The all-important connection was P&O, the British company that pioneered the use of steamships to carry government mail, troops and passengers, first to the Iberian Peninsula and later to the Orient, reaching India by 1842 and Hong Kong in 1845.

Southampton, where P&O set up a headquarters in 1840, was another nexus. Edwin Charles Sait, a chief cook for P&O in the 1860s, probably joined the company in Southampton as he grew up in nearby West Sussex. Born in 1834, Sait was the second son of an agricultural labourer.

Mary Ann Warner was working in Southampton as an assistant manager at the Docks Hotel, part of the P&O complex near the waterfront, according to an 1861 census. The third of eight children, Mary Ann was born in 1835 and grew up on 80 hectares of farmland owned by her father in Worcestershire. She married Sait at Malvern Link, Worcestershire, on November 1, 1864.

Edward was city reared. His precise origins proved frustratingly elusive for a long time. A Newman family Bible recorded that he was born in London in 1831, but several Edward Newmans were born around that period. Just as I was despairing of ever finding a link between Edward Newman of Chefoo and his London family, an internet friend found a death notice in the October 17, 1883 issue of the Southampton-based Hampshire Advertiser. This reported the demise of Edward Newman, late of the P&O Company’s service, in Chefoo, North China, and added the illuminating words: Newman was “the fourth son of the late John Newman, of Bloomsbury, London.”

This sounded rather grand; Bloomsbury was a fashionable quarter of mansions and garden squares. England’s 1841 census shows that Edward was the sixth of John and Ann Newman’s eight children. His father was a brass worker and two older brothers were apprentices in the same trade.

But it was their address, in Plumtree Street, that revealed the truth. The Newman family of 10 lived in a part of Bloomsbury that included the most notorious slum in central London. Known as The Rookery, it was described in one report as “remarkable for poverty and depravity, being the general resort of Irish, and where they first colonized at an early period”. Even the police were leery of entering this crowded, squalid area of pickpockets, prostitutes and beggars.

Little wonder Edward sought to flee as soon as he could. It isn’t clear when he joined P&O but, once he did, Southampton would have been a main port of call.

According to Duncan Clark, Edward had taken part in General Sir Robert Napier’s 1868 expedition to Abyssinia, to rescue a handful of missionaries and British government representatives held hostage by Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia. This sounded fantastic – until I found out that P&O vessels carried many of the troops and supplies, mainly from India, to the eastern shores of Africa for the huge and costly adventure. It’s not known if Sait was also involved in the Abyssinian expedition. In any case, he was struck down by heart and liver disease later that year and died on August 26, 1868, at his home, a short distance from the Docks Hotel.

Devastating though his death might have been for his family, it also opened up possibilities. Edward was approaching 40. After a career at sea, interspersed with sojourns in Hong Kong, where eligible women were virtually non-existent for a lower-class man, he was still a bachelor. Mary Ann was a handsome widow at 33, with one son.

When Edward proposed marriage, Mary Ann would no doubt have weighed the security provided by her large family against the risk of sailing to the other side of the world with a bachelor likely set in his ways. There was also a matter of propriety, as Victorian England required a mourning period of two years for a widow. However, practicality won over decorum and, not long after her husband’s death, Mary Ann embarked on a three-month voyage to Hong Kong, which also involved an arduous overland stretch as it was undertaken a few months before the opening of the Suez Canal.

The couple’s wedding at St John’s Cathedral and the subsequent newspaper announcements of their children’s births reflected Edward’s pride in his new status as family man. He also became a fully fledged Freemason at the Zetland Lodge in May 1872. With a young family, steady job and good connections, Edward appeared finally to have secured a foothold of respectability in socially conscious Hong Kong.

Then, in 1873, he gave it all up.

It was another new-found cousin, Graeme Clark, 73, a retired Australian army officer living in Queensland, who provided insight into the characters of Edward and Mary Ann Newman during this critical period. After piecing together our family intersections on the phone, I visited him when his health took a turn for the worse.

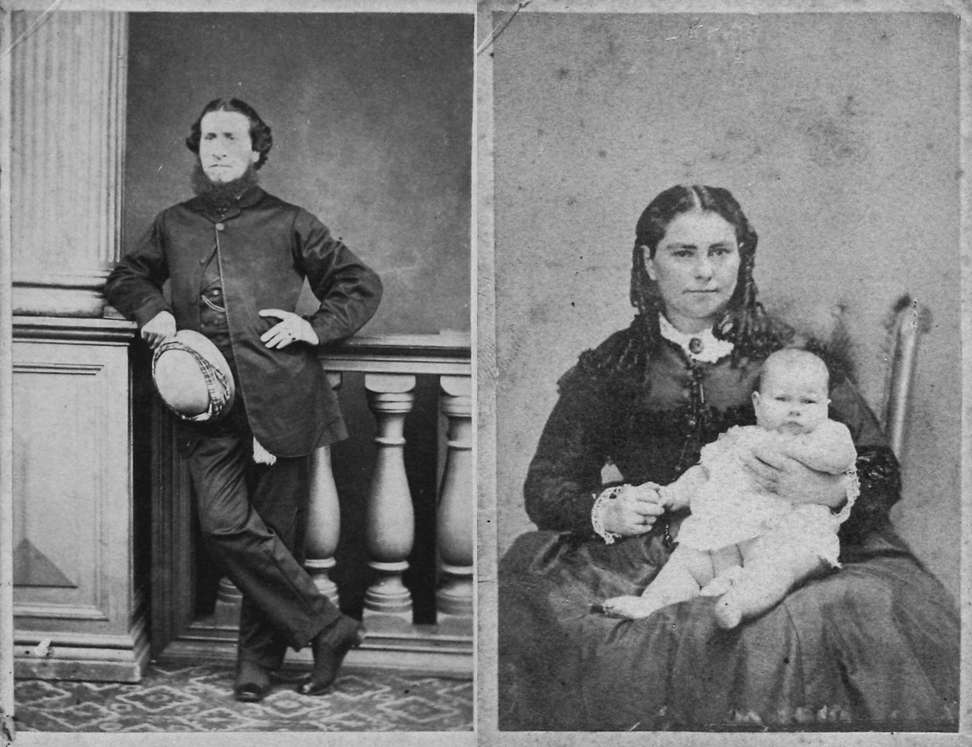

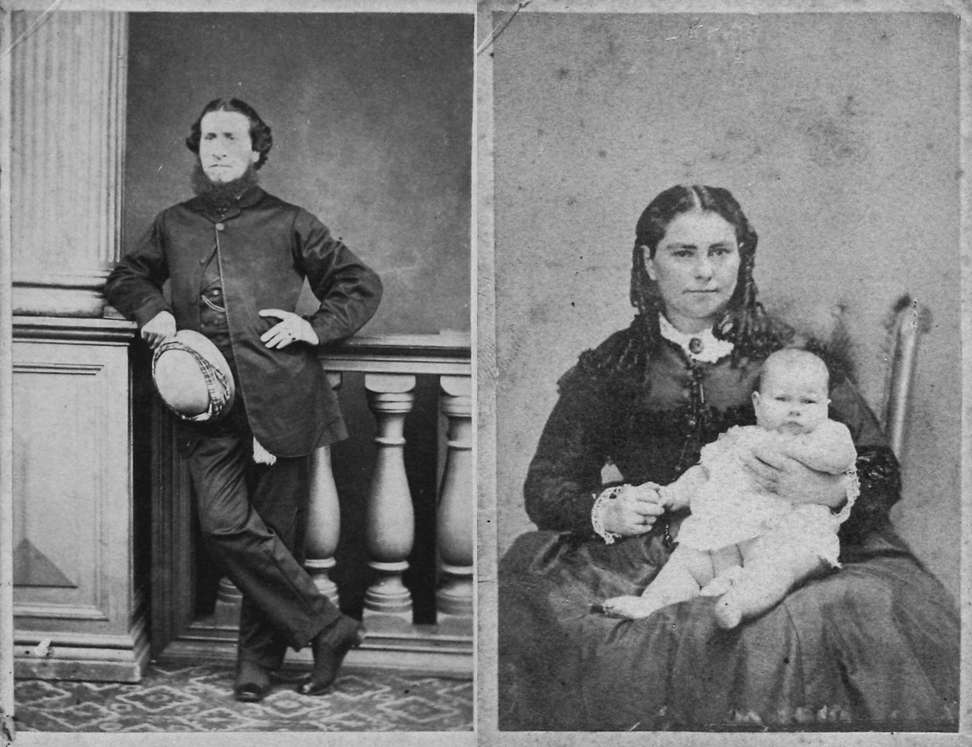

I was turning over the pages of his family albums when I came across what I had not dared hope for: the faces of the Newmans staring out at me. The black-and-white studio photographs, which Clark had forgotten about, had been taken in Hong Kong in 1871. One shows Mary Ann seated, with baby Annie on her lap, while another depicts Edward, standing beside a pillar.

Edward has a full head of hair and his formal attire is belied by a jaunty stance, with a hand on his hip and one leg crossed casually over the other. Furthermore, he is holding, with insouciance, a light-coloured hat that looks like a boater or a hat worn by a woman. To me, it suggests Edward was his own man who did not much care what others thought of him.

Mary Ann has a strong, round face and dark curls falling to her shoulders. She exudes calm and solidity as she clasps Annie with one hand while tweaking her baby’s finger with the other.

Yet she was supportive of her husband’s madcap venture, which must have seemed especially dangerous after the Tientsin massacre, in 1870, when an angry Chinese mob killed the French consul and some 60 Christians, including French nuns and priests, sending shock waves through China’s foreign communities.

Mary Ann may also have worried about Hong Kong’s unhealthy climate and high crime rate. On Old Bailey Street, the Newmans lived directly opposite Victoria Prison and they had only to walk outside to see Sikh policemen parading Chinese offenders in wooden stocks along Hollywood Road.

By contrast, the Newmans would have heard of Chefoo’s reputation as having the healthiest climate among the treaty ports, neither too hot in summer nor too cold in winter and free of tropical vapours.

But Chefoo’s main enticement for the Newmans was revealed when Wei took us to the site of the former Family Hotel. In 1874, according to a Chefoo directory, Edward and Mary Ann became proprietors of the hotel, taking over from Mr Bielfield, a German. So that was their siren call – the chance to be free from wage slavery and become masters of their destiny.

One more aspect puzzled me. Why had they bought a hotel that was a mile from the foreign quarter?

The answer came as we stood at the Haibinlou (Peace) Hotel, successor to the Family Hotel, and looked down at the bay’s only sandy beach in an otherwise bunded shoreline.

“This is still the No 1 beach in Yantai,” said Wei.

The Newmans found a small international community that included consular officials, missionaries and agents representing dozens of mercantile, shipping, insurance and banking enterprises. Some obligatory features of a treaty port were already in place: an Imperial Maritime Customs office, the Chefoo Club and the Chefoo Race Club, which held horse races every May on the beach.

But Chefoo’s anticipated commercial boom did not arrive and the Newmans must have wondered if they had made a disastrous mistake. For many years, Chefoo was isolated from its hinterland by dirt tracks that could accommodate only mules, horses and donkeys, not even carts. Thus, the port remained more of a landing stage than a trading centre.

There were other issues. The Chinese didn’t take to imports such as British cotton goods, preferring their own. Also, inadequate steamer services prevented foreigners from exporting as much beancake as they would have liked.

The British recognised the restrictions of Chefoo’s potential and never established a formal foreign settlement, with defined boundaries and a proper municipal council.

Meanwhile, the Newmans settled down to their new life. Unusually for Victorian wives, Mary Ann used her previous hotel experience as Edward’s partner in business while continuing to increase her family. On March 30, 1874, Edward signed the book at the British consulate to register their second daughter, Ellen, born the previous month. Another son, George James Thomas, arrived on October 4, 1875. Two years later, at the age of 42, Mary Ann delivered Amy Dorothy Edith, on August 31, 1877, but the infant died at three months. Between their family, staff and hotel guests, the Newmans led an eventful and largely self-contained life, avoiding the boredom that plagued so much of treaty port life.

Chefoo, fortunately, prospered through other ways beside trade. Warships of all flags were frequent visitors, keeping watch as China tried to create a modern fleet in the north. Above all, Chefoo’s European climate was a big hit with convalescents and retirees, as well as holidaymakers and officials seeking respite from the heat of Peking. All this was a boon for the Family Hotel.

In 1879, the Newmans benefited from a fantastic stroke of luck. James Hudson Taylor, the British founder of the China Inland Mission, had become seriously ill on a voyage back to China and was recuperating in Chefoo. One day, he was walking along East Beach with fellow missionary Charles Judd when a farmer approached them and asked if they wanted to buy his bean field. This encounter led to the development of a large China Inland Mission compound that would include prestigious schools for boys and girls.

The mission’s first building was a sanatorium on the other side of San Lane from the Family Hotel. Part of the hospital was used as a preparatory school, which opened in 1880 with three of Judd’s sons as its only pupils. In January 1881, they were joined by Frank Newman, eight years old, and his brother George, aged five. Later, the Newmans’ daughters, Annie and Ellen, attended the girls’ school.

Modelled on the British public school system, Chefoo School would acquire a reputation as the finest school east of Suez.

In anticipation of a boom, the Newmans added a second floor to the hotel. Not only was their gamble paying off, but their children were getting a better education than they would have had in Britain.

Then, on August 13, 1883, at the height of the summer season, Edward rose to cope with a typical day. But it turned out to be far from business as usual. Sometime that morning, he experienced a sharp pain, collapsed and died.

A death notice in the North China Herald, published in Shanghai, read: “At Chefoo Family Hotel, on the morning of the 13th of August, of Apoplexy, Mr. Edward Newman, to the great grief of his widow and family.”

On our final day in Chefoo, Wei drove us to Temple Hill, where Edward, and later Mary Ann, had been interred in the Settlement cemetery. Their tombstones no longer exist as the cemetery was razed in a wave of anti-foreign sentiment during the Korean war. However, I have photographs of their graves, courtesy of Duncan Clark. Edward’s bore the simple inscription: “Memory of Edward Newman, of the Family Hotel, who departed this life August 13, 1883.”

A resurgence of historical interest, among the Chinese as well as Westerners, has led to changing attitudes towards the colonial era. At the Yantai Museum, an exposition of life during that period, the official narrative, as expounded in the text accompanying photographs and artefacts, is that humiliation and suffering were imposed on the people of Yantai. Yet, as one of Wei’s friends, journalist Yang Jang, told us, his newspaper, the Yantai Evening News, had recently run a series of articles on the influence of the foreign era upon Yantai and had been largely positive. It was true that the foreigners had forced unequal treaties at the barrel of a gun. But they had also brought trade, hospitals and schools, street lamps and paved roads. Western-styled fruit-growing and wine cultivation were introduced in Yantai and both are major industries today.

This altering perception of the past was demonstrated in the way we were warmly received by Wei and his history-minded friends. Lin Weibin, a government official and collector of historical postcards, allowed me to photograph rare postcards of the Family Hotel. Hao Youlin, a former district official and editor of a cultural magazine, gave me a Chinese copy of a book, Glimpses of Chefoo, also featuring the Family Hotel. At our last lunch, our hosts toasted us repeatedly, saying it was an honour to meet a descendant of a family that had been a fixture of Chefoo for two generations.

I was touched. Our visit felt like a homecoming.