The threat to free speech, in Hong Kong and elsewhere, and 10 ways to safeguard it, according to historian Timothy Garton Ash

The British historian’s research shows an erosion of freedom around the world; on a recent visit to the city, he talked about the global conversation on freedom he initiated and ideas it has yielded

Timothy Garton Ash has arguably lived a far more exciting life than your average Oxford University don. The British historian, author and commentator was a student in Berlin when political magazine The Spectator asked him to cover what turned out to be the fall of communism in Germany. And despite having the sharp, critical intellect that makes him a perfect fit for academia, he has always kept a foot in the real world, writing newspaper columns and travelling widely.

Since his most recent book, Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World, was released last summer, he has passed through the United States, Canada, Germany, India, Poland, Austria, Hungary and several other European countries.

“It’s been a very intense time-lapse photography of the state of free speech around the world,” says Garton Ash, who spoke recently at a Hong Kong International Literary Festival event and to students at the University of Hong Kong.

Book tours are nothing new to Garton Ash – he has penned 10 works of political writing, including In Europe’s Name (1993), The File: A Personal History (1997) and Facts are Subversive (2009). But this one is different.

Britain has a certain responsibility for what happens in Hong Kong, but I’m afraid ... that post-Brexit, Britain is not very visibly standing up for human rights and free speech

“It’s not like another book where, in the Chaucer phrase, you say ‘Go little book and your fate will be what your fate will be’ and maybe I talk about it for three months at festivals, because this is an ongoing process,” says Garton Ash.

Free Speech is the result of 10 years of research and is part of a wider project that it spawned, the multilingual freespeechdebate.com website, which Garton Ash launched in 2012.

“The project in essence is John Stuart Mill meets the smartphone,” he says, referring to one of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and explaining that mass migration and the internet are leading us all to become “neighbours”.

“Anyone with a smartphone can theoretically communicate with half of humankind. But that also brings major risks and threats – cyberbullying, harassment and, of course, surveillance,” he says.

The project set out to provide a platform for debate about free speech and, to ensure that it is culturally diverse, it operates in 13 languages, including Chinese. One of the chief aims of this global conversation was to come up with a set of rules of engagement for free speech. After years of discussion and intense debate, 10 principles (see below) have been hammered out, although they’re not set in stone; Garton Ash is still open to suggestions.

“I have no illusions that the whole world will suddenly adopt them but, as a set which says how things should ideally be if we want to live together well in a world where we are all becoming neighbours but still remain free, I think they are pretty good,” says Garton Ash.

These essential principles, he believes, are the key to beginning a transcultural discussion about freedom of expression and freedom of information, a starting point for asking questions of governments and private superpowers such as Facebook and Twitter.

Garton Ash was determined that the discussion not be one seen only through the prism of Western thought, and having a transcultural conversation led to some interesting insights. For example, in the Western tradition, free speech is all about the speaking, but in the Indian tradition, there is as much emphasis on the listener and how to be a good one.

“Emperor Ashoka has a Sanskrit term that means the perfect listener. For a good conversation you need the good listener as well as the good speaker and this goes all the way through to Gandhi, who said in a lecture in London in 1931, ‘We need to open ears,’” says Garton Ash.

The Chinese model of ... information sovereignty ... is quite attractive to countries like India and Brazil

Chinese tradition also enlightened the debate. In his book, Garton Ash points to a group of leading Confucians who wrote to the highest authorities in Beijing to protest that the Southern Weekly newspaper’s 2013 New Year editorial had been rewritten to remove all references to constitutionalism. The letter drew on the history of Chinese political thought to make the case for free speech.

He also quotes the rebuke of the ninth-century-BC Duke Zhao to King Li of Zhou: “The repression indeed blocked the people from voicing their opinions. However, the consequences of muzzling them are more dangerous than damming the flow of a river. When an obstructed river bursts its banks, it will surely hurt a great number of people. People are like this, too. For this reason, those who regulate rivers dredge them and lead the flood; those who regulate people dredge [channels] and let them talk […]”

In 2012, when Garton Ash launched the website, he travelled around the world to talk about it, visiting Turkey, India, Egypt, China, Hungary, Russia, Hong Kong and other places.

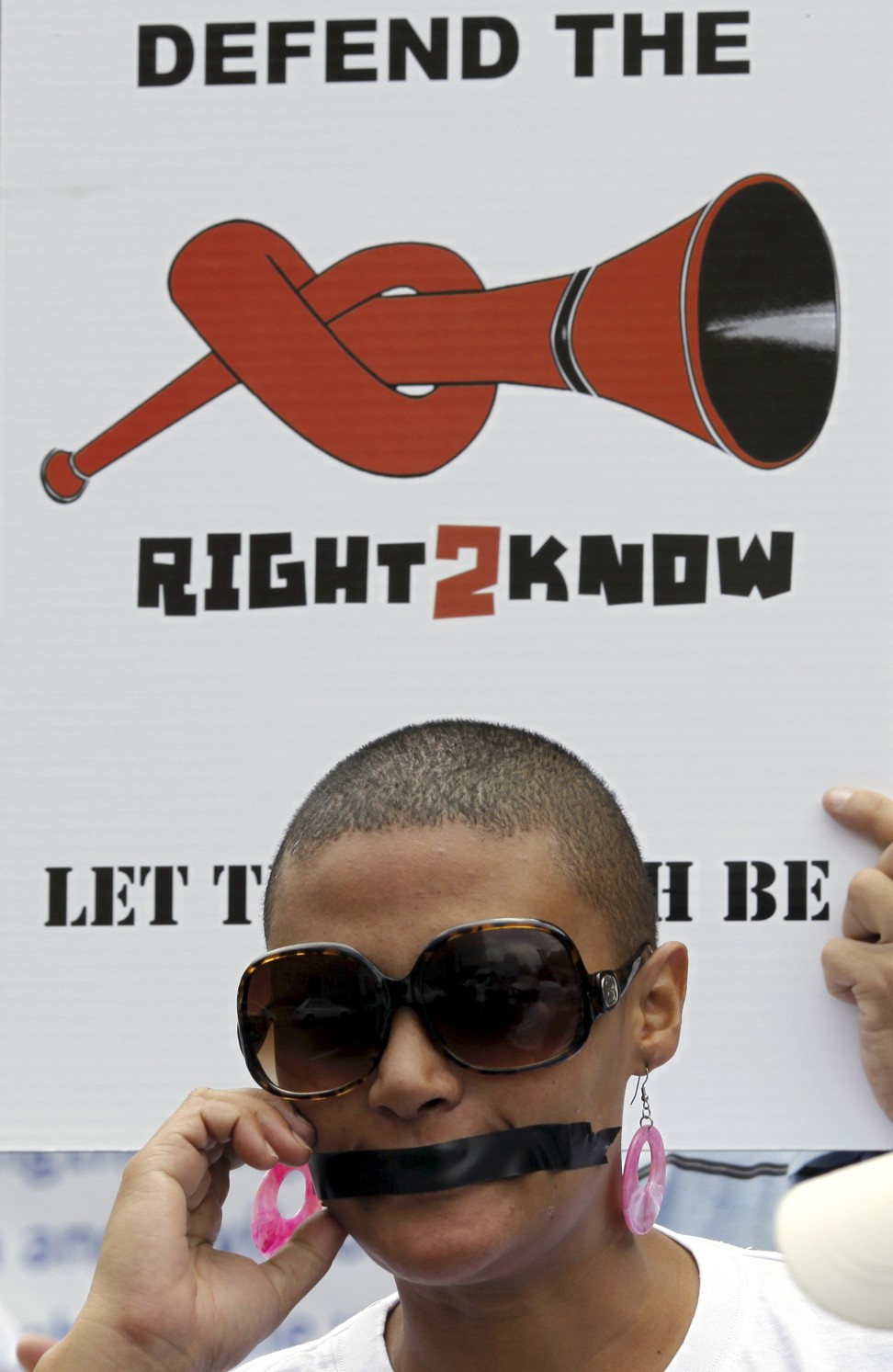

Now, “I’m going around the world talking about it again and in every single one of those places free speech is under attack and has retreated more,” he says. “That’s striking and depressing.”

What he has also noticed is that in all of those places, despite the issues being very different in each case, the tactics of those trying to suppress free speech are similar.

“It’s as if there are only so many tricks in the book and everyone is using the same ones,” says Garton Ash.

An increasingly familiar method of stifling free speech is to invoke a very broad definition of national security, such as that seen in Turkey, Egypt, Hungary and, to some extent, the US. Another common strategy is to control through ownership.

“Control through ownership, one of the key issues here in Hong Kong, is not direct pressure by the state, but indirect pressure exercised on owners who have other business interests,” he says.

While Garton Ash admits that Hong Kong has infinitely more freedoms than China, he is concerned about the pressures he sees building in the city – the abductions of five booksellers in 2015, the erosion of press freedom and perhaps of academic freedom as well.

“At least in theory Britain has a certain responsibility for what happens in Hong Kong, but I’m afraid – and this fills me with great sadness – that post-Brexit, Britain is not very visibly standing up for human rights and free speech. It’s trying to make deals and make trade arrangements and boost the economy.”

Nevertheless, he spoke very freely in Hong Kong – something he isn’t able to do in China. To begin with, he can’t show the Free Speech Debate website, as it was shut down there almost as soon as it was launched.

“Obviously, you can’t go in and give a lecture simply about free speech. But there are ways of talking about related issues that necessarily bring up the question of free speech. I will give lectures about Europe, about populism, the new media and so on. I think it’s really important to keep talking, to keep open the conversation and not to get into megaphone diplomacy.”

But the challenges of speaking freely in the mainland don’t dampen his enthusiasm for visiting, which he has been doing regularly for a decade, to give lectures at universities and meet think tanks and intellectuals.

He describes China as politically the most interesting nation on Earth, being the first to have what he calls “Leninist capitalism”. When he visited around the time of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, it seemed the state was working out a peaceful and pragmatic way of embracing a free market, a civil society and people’s aspirations, but he now sees a regression, with direction coming from the top.

“This year is the 100th anniversary of the Russian revolution so we have 100 years’ experience of Leninists of one kind or another in power and it doesn’t usually end very well,” he says. “And I say that with worry and concern because I actually think we should all be interested in a peaceful evolution of China.”

President Xi Jinping has overseen a return to what Garton Ash calls the “Leninist gamble”, the conviction that a single party under great leadership can manage the development of a complex society. He sees this as greatly diminishing the chances of a peaceful evolution.

A key aspect of the Chinese political system is the control of speech, the media and the guidance of public opinion. Party leaders would argue, says Garton Ash, that this model is not only working, but is proving attractive in other parts of the world.

“The Chinese model of what they call information sovereignty – saying the state will control the circulation of information, ideas and their frontiers – is quite attractive to countries like India and Brazil, which have a very strong post-colonial influence on sovereignty,” he says. “Also remember that China has invested very heavily in the media in Africa and Latin America, so I think Chinese soft power in that sense is growing.”

The demand for freedom of speech is not just about what the states should do, it’s also about what these private superpowers [Facebook, Google and Twitter] should do

He refers to India, Brazil and South Africa as “swing states”, places that may be decisive in swaying the global argument about freedom of expression and information one way or the other. In the wake of Edward Snowden’s revelations about states’ surveillance of their citizens, these swing states don’t like the idea of the US’ National Security Agency accessing their data or taking it from Google and Facebook, so they are exploring ways of controlling that data.

But it’s not just governments that are attempting to control freedom of speech – Facebook, Google and Twitter are just as powerful in this respect. What you see – or don’t see – on Facebook is the result of editorial decisions made behind closed doors by people who are not accountable.

“The demand for freedom of speech is not just about what the states should do, it’s also about what these private superpowers should do,” he says.

Bouncing around the world speaking about free speech, Garton Ash is all too aware that attempts to control information are a global phenomenon. So why is this happening now?

Garton Ash rolls the clock back to 1989, which saw a string of significant events that helped spread not only freedom and democracy, but also globalisation: the Tiananmen Square crackdown, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the fatwa on Salman Rushdie and the invention of the World Wide Web.

“Any historian would expect that if you have one great wave of movement in history, at some point there comes a counter wave, and this is, in many ways, a counter wave.

“It’s not just a pushback against liberalism – it is conscious anti-liberalism,” he says.

Ten years into his mammoth project, free speech is something Garton Ash is unlikely to ever tire of talking about. As he sees it, this is one of the key issues of our time.

John Stuart Mill meets the smartphone: 10 principles for engaging in free speech

1 Lifeblood We – all human beings – must be free and able to express ourselves, and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas, regardless of frontiers.

2 Violence We neither make threats of violence nor accept violent intimidation.

3 Knowledge We allow no taboos against, and seize every chance for, the spread of knowledge.

4 Journalism We require uncensored, diverse, trustworthy media so we can make well-informed decisions and participate fully in political life.

5 Diversity We express ourselves openly and with robust civility about all kinds of human difference.

6 Religion We respect the believer but not necessarily the content of the belief.

7 Privacy We must be able to protect our privacy and to counter slurs on our reputations, but not prevent scrutiny that is in the public interest.

8 Secrecy We must be empowered to challenge all limits to freedom of information justified on such grounds as national security.

9 Icebergs We defend the internet and other systems of communication against illegitimate encroachments by both public and private powers.

10 Courage We decide for ourselves and face the consequences.