Tackling slavery in the Thai fishing industry, one victim at a time

The Thai government claims it is regulating the fishing industry more tightly, yet slavery persists. One man, duped into the trade and whose nightmare ended a few years ago, is determined to pursue justice for fellow victims

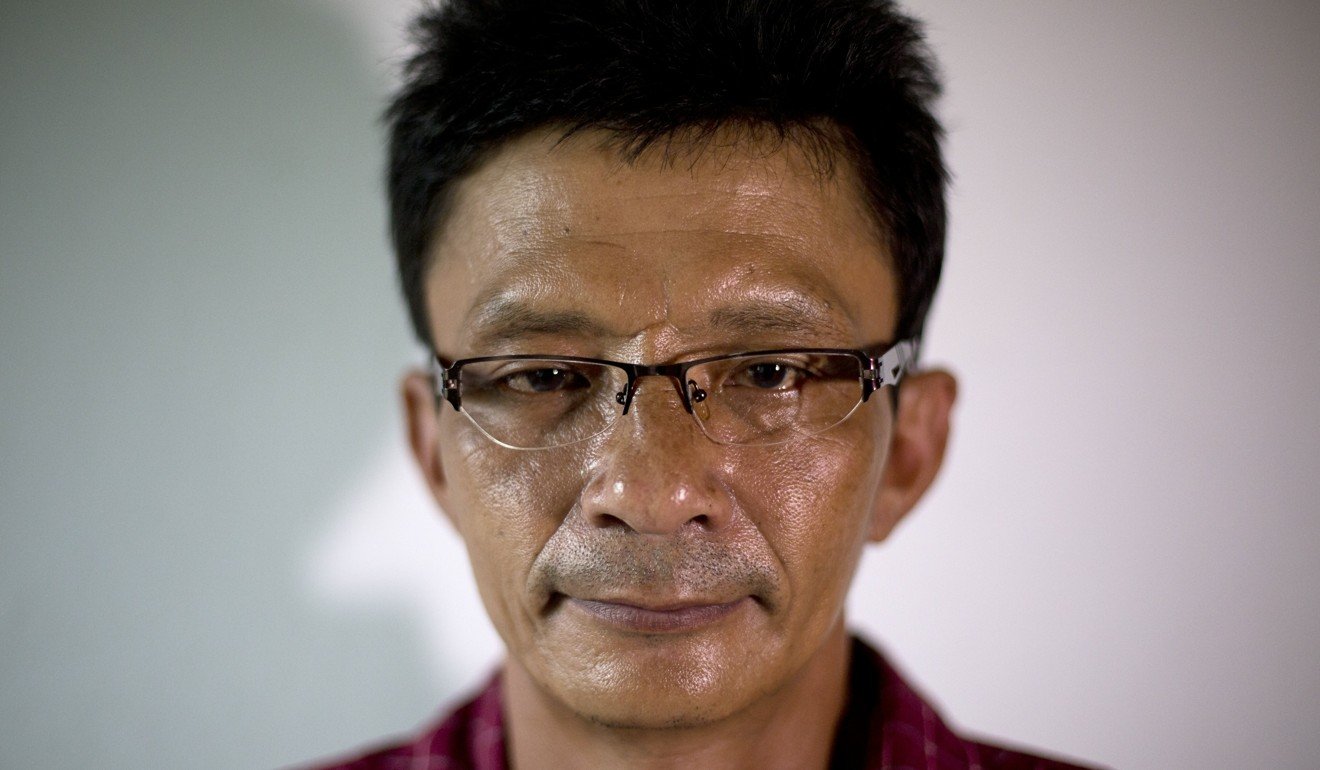

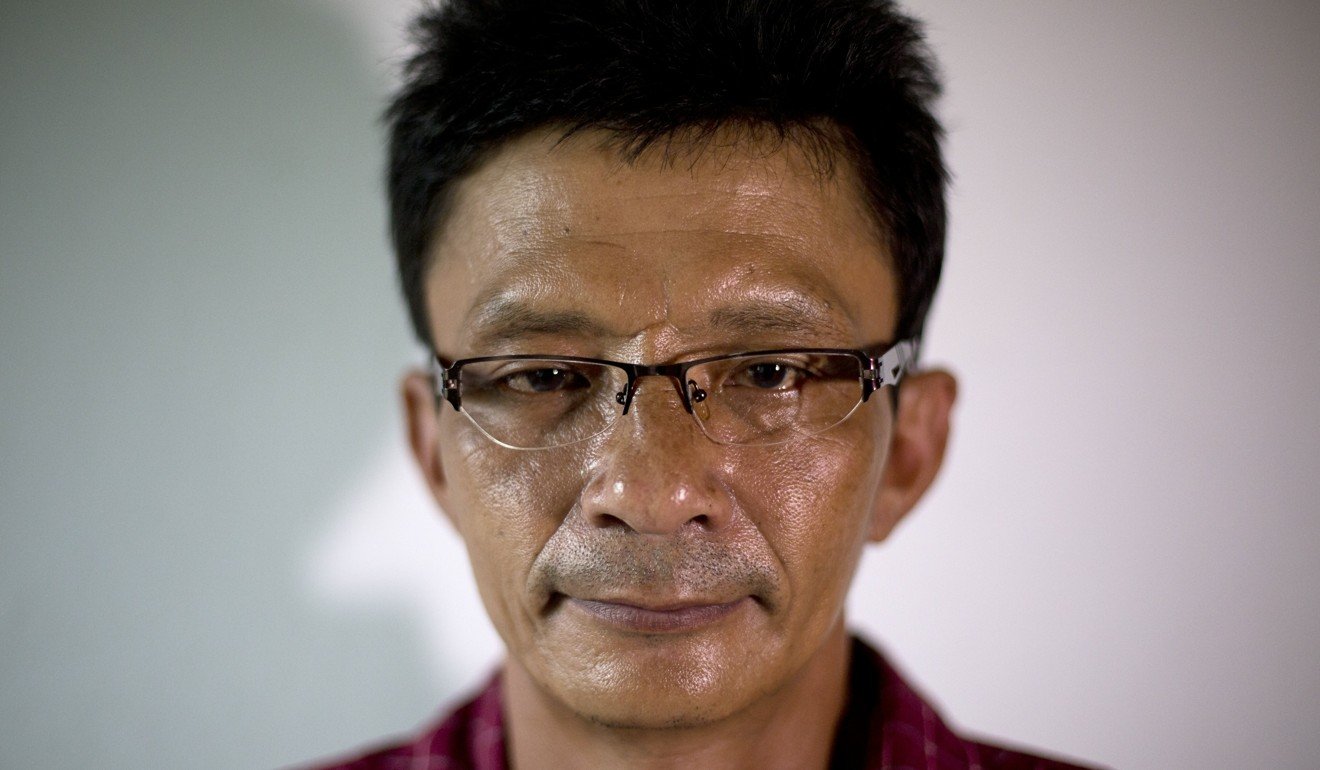

In 2009, as the financial crisis swept the world, Samart Senasuk, now 44, lost his job as a security guard in Bangkok. Unable to find work, he was preparing to return to his hometown, in Isaan, an impoverished region in the northeast of Thailand, when a friendly man invited him for a drink, to talk about a job on a fishing vessel.

Samart turned down the job but, after a few sips of his drink, he says, he passed out. When he woke, he was on a boat off Singapore – how he got there remains a mystery – and would soon be sent into Indonesian waters, where he would remain trapped for seven years.

Slave labour has been rife on the vessels that sustain the seafood industry in Thailand. The country is the world’s fourth-largest exporter of seafood, after China, Norway and Vietnam, according to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation, and Thai government figures show that Hong Kong is the industry’s fifth largest import market. Vulnerable migrant workers, mainly from Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos, but also impoverished Thais, have for years been lured onto fishing vessels with promises of well-paid jobs, although most never receive salaries. Others, like Samart, are drugged and kidnapped when they refuse to join a crew.

The issue is beginning to be addressed – the latest positive step coming this week, when Thai Union, one of the world’s largest seafood conglomerates, said it would overhaul its operations to protect against labour abuses and other bad practices - but it is difficult to establish how many people remain trapped at sea. The American State Department’s most recent Trafficking in Persons Report, issued at the end of last month, maintained the country’s ranking – which also takes into account those trafficked into prostitution and domestic work – at “Tier 2 Watch List” (the same level as Hong Kong), which is applied to countries and territories that do not fully comply with the minimum standards of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act but are making efforts to do so.

A few years ago, industry secrets began to leak out as reports in the media and by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) documented the working conditions on Thai fishing vessels and in the nation’s seafood-processing plants.

One of those media reports ended Samart’s nightmare, and now he devotes his energies to helping others who have suffered at the hands of Thai fishing captains.

“Being on a fishing boat is like having your life hang by a thread,” says Samart. “Nobody should experience this.”

Fishermen are overworked and physically abused, according to the stories told to Post Magazine by Samart and ex-fishermen he is assisting at the Thai and Migrant Fishers Union Group (TMFG), which is based in Mahachai, about 45km southwest of central Bangkok. Food is scarce and their passports and other documents are withheld.

“Some of them have to live with physical disability,” says Patima Tungpuchayakul, founder of the Labour Rights Promotion Network Foundation (LPN), an NGO that has been advocating for migrant workers’ rights in Thailand since 2004. “Some of their friends are killed.”

For Samart, the physical abuse began as soon as he came around.

“I shouted loudly when I realised I had been drugged and taken to the boat. And I was beaten,” he recalls.

His day on the trawler typically began at 7am, he says, when he would begin unfolding nets.

“The work was exhausting but we were not allowed to stop,” he recalls. He would labour until midnight, pausing only to wolf down the two or three meals the crew were fed each day – depending on how much work there was to do.

“Our lucky day was when we could catch very few fish. We could sleep early that day. If we caught a lot of fish, we couldn’t sleep that day and until the afternoon on the next day,” he says.

The crew slept on the deck floor, about 10 to a small cabin. When they finished fishing, they would prepare the nets for the following day. By the time they got to sleep it could be 3am or 4am; only a few hours before the start of the next exhausting shift.

In March 2015, news agency Associated Press (AP) found that fishermen were being held in captivity on remote Benjina, one of the 180 or so small islands that make up the Indonesian Aru archipelago, south of West Papua. Compelled to act on the report, Indonesian government officials visited Benjina and offered to send the men home.

“At first the men filtered in by twos and threes, hearing whispers of a possible rescue,” read a follow-up report by AP. “Then, as the news rippled around the island, hundreds of weathered former and current slaves with long, greasy hair and tattoos streamed from their trawlers, down the hills, even out of the jungle, running towards what they had only dreamed of for years: freedom.”

I want to be a volunteer because I have experienced the tough conditions on the boats

Officials found similar conditions on Ambon, an island 730km northwest of Benjina, where Samart and the rest of the 32-man crew, along with the boat they had worked aboard, had been abandoned by their captain. He had heard the authorities, who would bring in a moratorium on foreign-crewed trawlers in Indonesian waters, were inspecting fishing vessels. Samart says that he survived by doing odd jobs for islanders in return for food.

Samart’s luck then took a turn for the better; the LPN helped him with the complicated paperwork associated with rescued fishing slaves and he was able to leave Ambon not long after being abandoned. Some of those who were stranded with him would remain on the island for weeks or months longer. Instead of going home, Samart joined the organisation that had saved him.

With LPN’s assistance, Samart, and five other former fishermen, founded the TMFG, which aims to help victims of slavery in the fishing industry obtain compensation and reintegrate into society.

“I want to be a volunteer because I have experienced the tough conditions on the boats,” he says.

As I watch him work, Samart reads from a long questionnaire that Akharadet Silu, recently repatriated from Ambon, patiently answers.

“How long did you spend in the boat?” “Seven years.”

“How many hours a day could you sleep?” “Five or six.”

“What kind of job were you doing?” “I was catching fish.”

“Did you receive any salary?” “Never.”

Samart is working to build Akharadet’s case so he can take it to court and get compensation.

“I want to buy a house and start over,” says Akharadet.

Khon Sat, 33, who has come to Mahachai to discuss his case with Samart, had also been stranded in Ambon when Indonesian authorities began their inspections. He joined his crew willingly, he says, but he was not warned about the working conditions.

“It was too hard, we could barely rest,” he says. “We never knew when we would be able to eat. We could not stop until all the work was finished.”

Since September, TMFG has helped more than 60 victims rescued from Thai vessels operating in Indonesian waters. Khon is now among them.

At sea, any breach of the rules is punished and, despite many crew members being undernourished, stealing fish to eat is considered a serious offence.

“The captain jailed me [in a cage, in December 2014] because, he said, I allowed someone else to steal fish,” says 38-year-old Chairat Ratchpaksi.

Chairat was to spend four months in a cell with 17 others on Benjina before the LPN became aware of their plight and alerted the authorities.

Death can await crew members who cross their captains. A 2009 survey by the United Nations Inter-Agency Project on Human Trafficking found that 59 per cent of migrants trafficked aboard Thai fishing boats who were interviewed reported witnessing the murder of a fellow crew member. And accidents, some serious or even fatal, are frequent among the weary crews.

“We panicked every time a big wave crashed against the boat,” says Samart, who permanently lost the mobility in two of his fingers when they became trapped in a net. “I had deep wounds but there were no first-aid kits on the boat. I had to cover the wounds with clothes.”

Tun Lin, who was trapped on Benjina and now works at the TMFG, lost four fingers of his right hand – they were chopped off when he was handling a net. He, too, could find nothing on board with which to treat his wounds.

Samart’s boat would stay at sea for seven or eight months at a time, where it was supplied by smaller vessels, which would transport the catch to shore.

Transshipment at sea – the shipment from big craft to smaller ones – has become a common practice in international fisheries, allowing the larger vessels to stay operational for months or even years without returning to port,and beyond the reach of inspectors. Transshipment, activists say, allows the laundering of catches made illegally, such as those that exceed quotas established in an attempt to conserve fish stocks.

“[Transshipment] should be banned because it is a huge loophole in the regulations governing what happens at sea,” says Anchalee Pipattanawattanakul, ocean campaigner for Greenpeace Southeast Asia.

The practice has also turned the fishing vessels into floating jails, and Ambon and Benjina became crucial to their operation. Ports on the islands were remote enough to avoid unwanted inspection and officials there were willing to look the other way.

Whenever Samart’s boat headed to port on Ambon for maintenance, he would rack his brains for an escape plan.

“I could not fall asleep, thinking of how I could escape,” he says. In port, the crew could leave the boat but were kept on a short leash by the captain and the local authorities. He tried to run on more than one occasion, he says, “but I was always returned by the port authorities”.

Tinnakorn Naonan worked “every day all day, even when it was raining” on a smaller boat, which unloaded its catch in Ambon once every two months. In port, fishermen were allowed two days of rest, he says, which they would spend on the island. They were not questioned by officials who should have been checking that unregulated fishing and human trafficking wasn’t going on under their noses.

Tinnakorn had visited Mahachai from his hometown in western Thailand hoping to find work on one of the small fishing boats that remain close to shore and return to port regularly. He was offered a position classifying catches as they arrived in port. He boarded one boat and would not step off again for seven years.

“We could never sleep more than six hours a day,” he says. “Normally five hours at night and one more hour during the day.” He had been promised a salary of 3,000 baht (HK$685, US$88) a month, he says, but has not received any payment.

Many fishermen are deceived or kidnapped by brokers, who sell them to Thai captains. They typically pay between US$500 and US$1,000 per slave, an amount workers are required to pay back from their wages, real or imagined.

Samart was told that he could not leave his vessel until his debt had been settled.

“I had never borrowed money from anyone,” he says. In seven years, Samart received no salary. “We were only receiving some money when we were on the island,” he recalls. He had no way of knowing whether his “debt” had been repaid because he did not know how much he was supposed to be earning.

Penniless and, in many cases, physically damaged, long years of abuse also leave victims bearing scars of a different nature. Samart still suffers from nightmares and anxiety, he says, but “some of the fishermen I help even suffer from hallucinations”.

“Some have been away from home for more than 10 years,” says Patima. “All the workers cry to me. They cry for help to return home.”

The nature of the trauma suffered by fishermen on the boats is complex, says Katherine Welch, a doctor based in Bangkok who specialises in treating victims of human trafficking.

“Victims often commit crimes [such as theft and drug abuse] in the course of being trafficked. This can create legal problems for them as well as overloading their sense of guilt and shame and impacting their healing,” explains Welch.

Furthermore, “after slavery, there is an increased vulnerability to be victimised again. Victims were ‘used’ so they can think that they are not good for anything and get used over and over”, she says.

Most never receive professional mental-health care, but talking to other victims can help them avoid falling victim again.

They assume that, if you are an employer, you can punish your worker. For them, this is not abuse.

“I try to relieve their trauma. I talk to them because I know what they have been through and I can understand them,” says Samart. “When I left the boat, I needed the same.”

Following the reports in the media, and a warning from the European Union that if Thailand didn’t clean up its act, member countries would stop importing Thai seafood, Bangkok embarked on a programme of reforms focused on combating illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU), with a new regulatory framework approved in November 2015.

“Our fisheries law was obsolete. It was about 60 years old,” says Adisorn Promthep, head of the Thai Department of Fisheries. “It was not suitable for the [current] situation.”

Political instability, says Adisorn, has been the main reason for delays in approving new regulations. Since 1932, when absolute monarchy was overthrown, Thailand has endured 12 successful coups d’état. The latest, in May 2014, brought to power the military junta that is now overseeing reforms.

Most of the changes focus on licensing requirements and monitoring systems, but some improvements have been made to the legal framework that allows victims to obtain compensation. A special court on human trafficking was established and cases are now dealt with more speedily.

“Before, it could take four or five years to finish the case. Now it is only six months,” says Papop Siamhan, coordinator of the Anti Human Trafficking in Labour Project at the Human Rights and Development Foundation, an organisation providing free legal assistance to migrant workers.

Nevertheless, the judicial system adopts change only slowly, activists say.

“There isn’t a clear definition of forced labour [ìn Thai legislation] and judges tend to think that it is the same as human trafficking,” says Papop.

Akharadet’s case is a straightforward one, since he was, like Samart, drugged and kidnapped. For Khon, who willingly joined his crew, the process will be more complicated, despite the abuse he claims he suffered.

“They assume that, if you are an employer, you can punish your worker,” explains lawyer Chonticha Tangworamongkon. “For them, this is not abuse.”

The government says the new regulations will ensure that the rights of fishermen are respected and that they will no longer be forced to work on vessels against their will.

“Now we check that every worker that goes out [on a vessel] has a work permit [...] And we don’t allow [anybody] to work without a written contract,” says Adisorn.

In theory, every commercial vessel entering or leaving a Thai port is now inspected – the so-called Port In/Port Out system – and commercial vessels are required to install GPS systems so their activities can be monitored.

In response, the US State Department last summer changed its Trafficking in Persons ranking for Thailand from Tier 3, the worst, to Tier 2 Watch List. However, activists say, that does not mean the Thai fishing industry is slave-free.

“The upgrade represents a recognition that Thailand has started to take action on this issue [...] It doesn’t necessarily mean that the problem has been solved or real progress has been made,” says Daniel Murphy, an independent researcher specialising in the fishing industry.

According to Murphy, the government has focused on Thai waters while the distant fleet, where abuses are more common, “has not been subjected to the same standards” in the enforcement of the law.

Greenpeace published a report in December accusing Thai fishing vessels of moving to more distant waters, out of range of the Thai authorities. However, the environmental group described last week’s Thai Union announcement, which also claimed the conglomerate would allow independent observers and tracking devices on boats, with Greenpeace monitoring implementation, as “huge progress”. It is hoped that others in the industry will follow Thai union’s example.

Corruption, though, plays a major role in perpetuating human trafficking onto the boats.

“This is part of a larger problem of extortion of migrant workers by police that has been a consistent problem but which no government has really been willing to touch,” says Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division.

And what of Benjina and Ambon? “The moratorium on foreign vessels operating in Indonesian waters that forced the vessels to stations like Benjina and allowed for the rescue of those fishermen was lifted some time ago,” says an officialat the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). “We have no specific information about the Benjina facility reopening at this time.

“That said, the [Indonesian] government has taken deliberate action to protect the rights of men working in the fisheries and IOM is working with them to enhance the ability of front-line responders at sea, including the navy, coast guard, water police and others, to identify possible victims of trafficking and render assistance.”

Meanwhile, Samart continues to receive victims as they are processed from Ambon and Benjina. He waits for them at Bangkok’s airports, showing a friendly face when they arrive and trying to convince them that their nightmare is over.