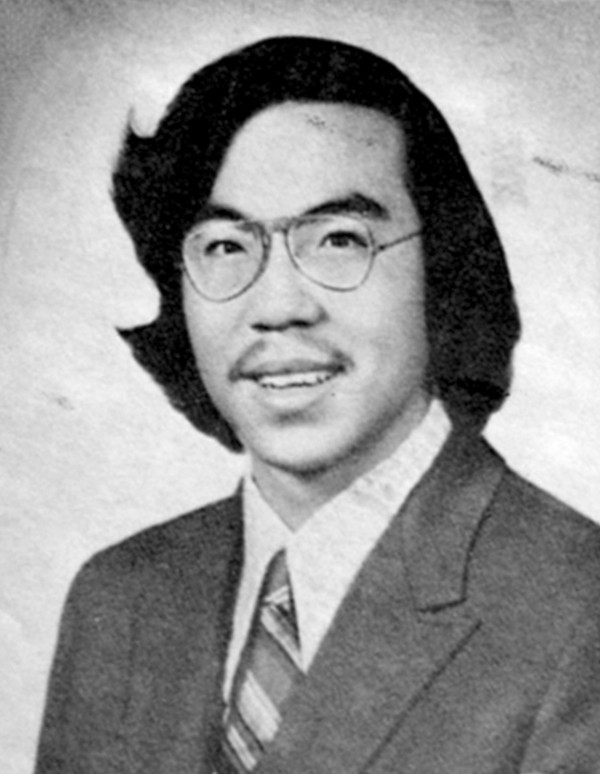

Stewart Kwoh, lawyer fighting for Asian American rights, on what drives him

The founder of the Los Angeles-based civil rights group Asian Americans Advancing Justice, talks about his Hollywood actress mother Beulah Quo and the Vincent Chin murder case

MADE IN CHINA My parents were both Christian. My father was from Shanghai and his family owned a printing company, called Commercial Press, that printed Bibles. He went to the seminary at Princeton University for his undergraduate degree and earned a PhD in education from Columbia University. He met my mom at a graduate Chinese Christian association. Her family was originally from a village in Guangzhou and she was born in Stockton, California. She went to the University of California, Berkeley and then to the University of Chicago. My parents went to China to help rebuild the country and taught at Ginling University (in Nanjing) – that’s where I was born, in 1948.

IMMIGRATION NATION When I was two months old they moved back to the US and we lived in northern California for two years and then in Los Angeles, where I’ve lived ever since. Los Angeles is a diverse city and our neighbours were Mexican American, African American, Middle Eastern, white and Asian. The 1965 immigration law that was fully implemented in 1968 ended years of exclusion and allowed Chinese to come to the US. I observed a lot more Asians coming in from the 1970s – every decade there was a doubling of the Asian-American population.

HOLLYWOOD MOTHER My mother was a professor but she became a Hollywood actress. Her stage name was Beulah Quo. A family friend who was an actor made the introductions and she got a job on Love is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955) – she played the aunt of Jennifer Jones – and that led to more than 100 films.

Her best friend was George Takei, who played Mr Sulu in Star Trek, and she was friends with Gregory Peck – they would come to the house. She received an Emmy nomination in 1978 for her performance as Cixi, dowager empress of China, in an episode of Steve Allen’s Meeting of Minds TV series and she played Kublai Khan’s empress in the NBC miniseries Marco Polo (1982-83). She was a regular on ABC TV’s General Hospital, where she played Olin, a maid, for six years. She was a Phi Beta Kappa from UC Berkeley with a master’s degree, but she constantly played maids.

She was one of the busiest Asian-American actresses in Hollywood in the 70s and 80s. She was also a judge at the Miss Universe contest for two or three years. I never got to go. I think my father went once. My mother loved to help other Asian-American actors because minorities didn’t have much of a chance in Hollywood.

My mother was a professor but she became a Hollywood actress. Her stage name was Beulah Quo ... She was a Phi Beta Kappa from UC Berkeley with a master’s degree, but she constantly played maids

THE GOOD FIGHT I went to public schools and eventually to the University of California, Los Angeles for my undergrad as a pre-med major. As a student I was active in setting up the Asian American Studies programme and was president of the Asian American Student Association during the anti-[Vietnam] war demonstrations. The National Guard arrested some of our members and I was busy getting them bailed out of jail. Instead of applying for medical school I decided to apply for law school at UCLA – it seemed more relevant at the time.

As a college student I started a youth programme in Chinatown. Most of the low-income people I was working with spoke Cantonese, so immediately after my undergrad I came to Hong Kong on a six-month Yale programme to learn the language. I won’t tell you what grade I got, but I learned some Cantonese and went back to LA. It was then that I met the woman who would become my wife – she was a volunteer on the programme I had started.

She was born in Guangzhou, moved to Hong Kong in the early 50s, when she was five years old and, when she was 14, moved to the US. She was very bright and a computer science major at UCLA. We dated, then married and we’ve been together for more than 41 years. We have two sons – one is a psychiatrist and the other is an industrial engineer.

In 1983, after doing some private community work, I set up what was then called the Asian Pacific American Legal Centre and is now called Asian Americans Advancing Justice. The first big case we took on was that of Vincent Chin, who was killed by two white autoworkers in 1982. They thought he was Japanese and cursed him using racial epithets and beat him to death with a baseball bat. The following year the killers pled guilty but were sentenced to only three years’ probation and a US$3,000 fine. I called Vincent’s mother (Lily Chin) in Detroit, Michigan, and asked if I could help.

QUEST FOR JUSTICE I helped devise a plan to get the federal government to file a federal civil rights case against the killers. We were campaigning in a packed Chinatown restaurant and Mrs Chin fainted. Later that day – she was staying at my home – I asked her if she was OK. She said, “Stewart, there’s nothing I can do to bring Vincent back, but I don’t want another mother to go through what I’ve gone through.”

Sadly, our quest for justice failed and Mrs Chin went back to Guangzhou in 1987. I brought my family to see her in 1995. She was smiling, but behind the eyes I could tell she had lost everything. Her husband died six months before Vincent, her only son, was killed, so she had no more family.

LEGAL EAGLES The justice system in the US had failed and I decided I would try to build the strongest civil rights legal group for Asian Americans in the US. Today, we have 100 staff and more than 800 volunteers. We do legal services, civil rights services, research, education and advocacy. We work with a lot of women on domestic violence cases and help thousands of immigrants to become US citizens. We are trying to protect some of the undocumented youth in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals programme, which President Donald Trumpsaid he would end.

We are by far the biggest Asian-American non-profit legal organisation in the US.

SLAVE LABOUR Mrs Chin was our inspiration to fight for justice. My mother did a play about that story – she played Mrs Chin. We have had other big cases. In 1995, a neighbour asked for help on a labour investigation. We found 80 Thai workers – mostly women, just four men – locked up and forced to work. It was a slave shop, not even a sweatshop where they could come and go. Some had been locked in there for seven years sewing clothes.

It became an international case and we worked on it for five years. We won a major settlement and the workers were able to stay in the US and we helped them become US citizens.

A LIFE’S WORK The 1970 census had 1.4 million Asian Americans in the whole country and today there are more than 21 million Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. We’ve helped almost 300,000 people with immigration, domestic violence and other kinds of cases. My work has always been helping the vulnerable, the underserved – that’s where I get the greatest satisfaction.

Stewart Kwoh was in Hong Kong to present the findings of a study conducted by the Global Chinese Philanthropy Initiative, at the Asia Society, in Admiralty.