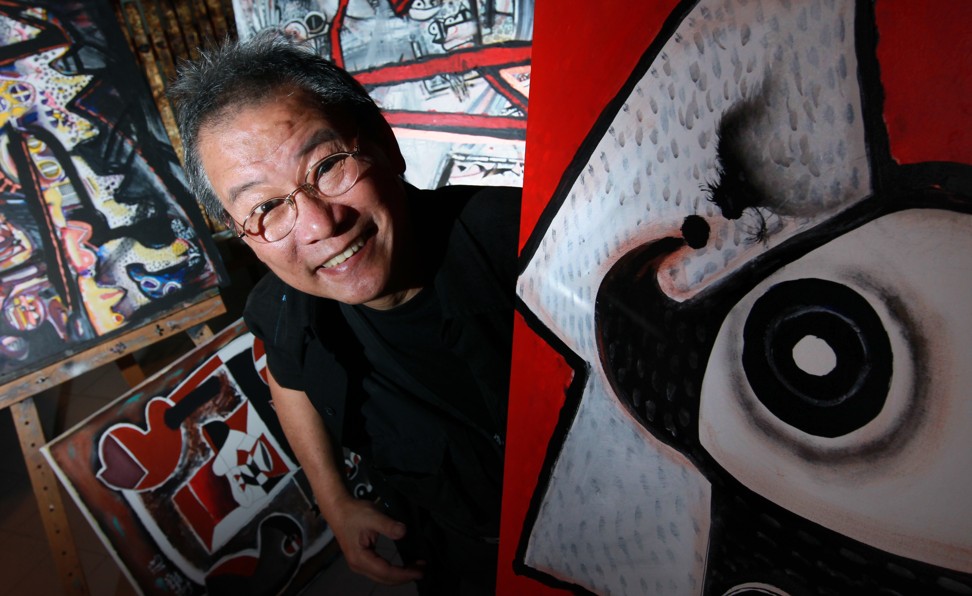

Hong Kong’s eccentric Frog King stays one jump ahead of the art-scene pack with madcap desire to spread happiness

From his jungle lair in Yuen Long, in the city’s New Territories, the eccentric force of nature and living work of art – who is now possibly 70 years old, possibly not – continues to create and surprise

The performance artist known as Frog King lives up the sort of tangled, overgrown path that makes you think less about frogs and more about snakes (although the greater immediate hazard is probably the mosquitoes). Here, he hunkers down alone, working day and night.

All available space – including an abandoned chicken farm and an old pig pen – is crammed either with his creations or encroaching nature.

While researching this article, I’d read an essay by Benny Chia Chun-heng, founder of Hong Kong’s Fringe Club, who curated Frog King’s show at the 2011 Venice Biennale and said that the artist had wanted to take over the Hong Kong pavilion with a forest of installation pieces, “just like the trees at Angkor Wat”. Budgetary constraints curtailed that dream, but it appears to be coming true on the outskirts of Yuen Long.

Given the location, I wasn’t entirely sure beforehand which avatar would present itself: Frog King or Kwok Mang-ho, the man behind the amphibian and a presence on the Hong Kong art scene since the 1960s.

In recent years, Kwok seems to have been swallowed up by Frog King, but I thought he might use the opportunity to re-emerge from the undergrowth.

Amid the banana trees, bamboo and bougainvillea at the far end of the lane, however, a glittering figure appears at the appointed hour, swaying from side to side like a sorcerer revving up for a ritual. In the ’70s, Kwok created his own Chinese term for an art happening – hark bun lum, which phonetically sounds like “arrival of the guest”. For Frog King, it’s a form of artistic noblesse oblige: a happening starts with the entrance of the audience, no matter how small.

Still, he’s not entirely averse to breaking the fourth wall, and there is a brief consultation with the photographer (should he switch the light attached to his hat on or off?) before he plucks a pair of Froggy sunglasses from a row hanging over his desk, drapes a piece of Froggy-carved wood round his neck and picks up a toilet-roll holder to wave as a sceptre.

While Frog King poses outside, I help myself to the mosquito repellent he keeps on his desk, and sift through a batch of recent photos he has had printed. Later, when asked what he does with his money, he’ll show me the receipt: HK$943. He’s also just spent HK$1,900 making photocopies of his froggy works, which he flings around, confetti-style, at his performances. His mission is to make audiences happy, and I’m sure Yuen Long’s print shops are cheered, too.

Tsuchiya had photographed the ’80s art scene on the Big Apple’s Lower East Side and was one of the founders of the underground Rivington School movement. These tributes, which he sent to Tsuchiya’s daughter, consist of inked statements – Toyo A True Underground Eye and East Village Art History and Roar, Art Jungle – and reference a vivid time in Kwok’s past.

“Toyo is a very kind person, diligent and concerned about everybody,” says Frog King, sadly, once the photographer has left. Every time he says anything particularly personal, his voice grows quieter, as if Kwok is speaking from somewhere inside, behind the layers of Frog King.

When he tells me that his third wife, an artist called Cho Hyun-jae, is recovering from illness in Korea, I can hardly hear him.

Soon, he makes some tea and begins pulling out slides and old catalogues. Although a cold weather warning is imminent, a furred air-conditioner is pumping away to offset the damp. There is a strong whiff of dog from numerically named Yat and Yee, who came with the house. Frog King tells me that rats have been using the ceiling as a racetrack, and several large ants run over my notebook while I am scribbling.

I feel mildly anguished that such vital evidence of Hong Kong’s art history might end up like the mouldy rubbish Kwok enjoyed working with earlier in his career. “Don’t worry!” he says. “They’re already printed out by Asia Art Archive.”

When Kwokarrived in New York in 1980, he was already well-established in Hong Kong, and his nascent frog instincts surely recognised it was a shallow pond. He’d held his first one-man show in 1967, at Grantham College of Education (now folded into the Hong Kong Institute of Education), when he was either 19 or 20; the arithmetic shifts because, although he’s adamant he was born in 1947, his Hong Kong ID card and his US passport both state 1948.

Weiwei called me when he cannot get out of the country. He said, ‘Soon the world will know Frog King.’ But I believe my energy is small. I do the small job. I do what I can do. His job is big

By 1975, he’d won an award for a sculpture of burnt piping at the Hong Kong Museum of Art’s contemporary show. Later that year, he performed an unscheduled happening at the museum called Splashing Cow Bone Action; the bovine bones he scattered on the floor were also burnt.

A fascination with fire runs deep, it seems. At the age of five and living in Causeway Bay, Kwok was holding a firecracker, just to see what would happen, when it exploded. He was taken to hospital.

“My 10 fingers were bleeding!” he cries. “I find a high feeling and I forgot the pain!”

His fingers survived, though today it’s rather hard to be sure – as Frog King, he is wearing a black, be-ringed glove on one hand, and a fingerless one on the other, and both arms are thickly encrusted with bracelets.

And adulthood doesn’t seem to have brought caution. In the ’70s, he was teaching at the Heung Yee Kuk Secondary School in Yuen Long, where he encouraged his students to ignite rags and a carpet for an open-day event that also featured toilet bowls, live chicks, bed springs and pencil sharpenings.

“It looked as if a cyclone had hit the school,” reported the South China Morning Post. (That he now lives in Yuen Long isn’t a coincidence. He clearly wasn’t the sort of teacher you forget, and one of his former students suggested his family’s old place when Kwok was looking for somewhere spacious to live last year.)

Other snaps show him at the Summer Palace and in front of Mao Zedong’s portrait in Tiananmen Square, waving his inflated “air sculptures” without evident political intent; the weightiest aspect could well be his ’70s moustache and hair.

Perhaps such apparent blitheness is why he’s not better known internationally, unlike, say, Cai Guoqiang, who is famed for his pyrotechnic marvels, or, to mention a more obvious example, Ai Weiwei, who, as a Kwok contemporary in New York, sold portraits on the streets to make money.

“Weiwei called me when he cannot get out of the country,” Frog King says at one point. “He said, ‘Soon the world will know Frog King.’ But I believe my energy is small. I do the small job. I do what I can do. His job is big.”

Kwok seems to have decided that the most important job is to stimulate people’s happiness. As we look through the photos, I can see the ones that give him the most pleasure are of an audience, of any size, beaming and waving their hands in front of him.

In the summer of 2013, he was invited to Papa Westray (population 90) in Orkney, Scotland, and he looks at the images of grinning islanders with something close to tenderness.

In the 2011 Venice Biennale catalogue, there’s a telling dialogue between Frog King and his three curators during which Chia expresses curiosity about why the artist chooses such words as “love”, “world peace”, “fun” and “harmony” to describe his work, and adds: “These sloganised values are antithetic to the very premise of contemporary art.”

Frog King replies: “I use these easily acceptable slogans to encourage the audience to participate and communicate.”

I am curious to know how he afforded his New York life, and he says his mother and his first wife, a teacher called Frances Fung, sent him money. He would work all night, as a cleaner in a restaurant and bar, before going to morning class at the Art Students League.

After his student visa expired, he stayed on illegally. There were moments of deep self-doubt. One distressed day, according to an essay written by Cho, he saw a frog leap, many times its length, into a pond. Out of that moment, an artistic icon was born.

The beauty of a frog logo is its simplicity and its ability to symbolise whatever you choose: a boat, a bra, a mountain, a pair of watchful eyes … Such flexibility, as Pepe the Frog’s appropriation by the American far-right recently showed, is also its downfall. I ask Frog King if he knows about this adoption, but he says no, which is probably just as well.

Back in his New York, his frog symbolised a bridge between East and West. He loved the amphibious ideal of being able to sail between cultures.

While I am peering at a tiny version of one of these in a collage, he says, helpfully, “David Bowie.” I look closer. It is, indeed, the Thin White Duke, wearing the king’s glasses.

In 1995, he returned to Hong Kong. His mother, then 80, had fallen and broken her hip in two places. “I saw her,” he says. “I felt it was my time to come back.” She recovered and lived to be 98.

In a book that Frog King published in 1999, called Kwok-Art – Life For 30 Years 1967-1997, there’s a photo of him doing her washing as Mang-ho, the filial son, not the outrageous magician, yet still, somehow, acting out a role. It was part of a selection he’d labelled “Daily Life as Performance ’90s HK”.

Today, I didn’t want to wear this outfit. But I know the newspaper needs it to attract people to look at what I do. It is my responsibility to put it on

Every night after his Hong Kong return, he went out into the streets and picked up discarded furniture with which he filled the 400 sq ft flat. That’s what he does with any space, as if he can’t bear physical emptiness, not even within a plastic bag. His unit at the Cattle Depot Artist Village, in Ma Tau Kok, is equally packed.

“Craziness!” he says now, looking around his Yuen Long residence. “I like clutter.” But I notice that his actual work area, though crammed, is highly ordered.

Can Frog King create art at 2am when he’s not actually dressed as Frog King? “Frog King creates 24 hours, non-stop,” he says. “He continues creating in his sleep.”

The isolation in this setting, in the depths of the rustling night, must be considerable. “The ghosts think I’m a shaman,” he says. “They’re afraid of me. The dogs bark for no reason … The ancestors are walking around.”

Luckily, although he says he’s not interested in money and spends it very quickly (I believe him on both counts), he’s represented by 10 Chancery Lane, a gallery that can channel the results of spooky working hours into usefully solid profit. In honour of his 70th birthday, on February 28, 2017, it arranged a series of Frog King performances.

“He liberates people and that is his gift,” says the gallery’s founder, Katie de Tilly. “People arrive expecting some kind of show, as if he’s there to entertain them, but he’s there to bring something out of you.”

Of course, according to Hong Kong officialdom, Frog King will turn 70 on February 28, 2018, which could provide more celebration. For Art Basel Hong Kong, at the end of March, the gallery is going to recreate the Kwok Calligraphy Shop, first shown in 1992 at the New Museum, in New York. There, Frog King will do his calligraphy and people will be able to take part in the Froggy Sunglasses Project.

At the beginning of our conversation, immediately after the photo shoot, I urged him to change his clothes but he refused. Towards the end of our afternoon together, he says, “Today, I didn’t want to wear this outfit. But I know the newspaper needs it to attract people to look at what I do. It is my responsibility to put it on.”

When I leave, he says, he’ll take it off and hang it in “its right place”.

I hoped to see the moment of transition, but the truth is that after several hours together, I’ve almost forgotten he is wearing it. It is only after we’ve walked down the path (Frog King gazing longingly at an utterly decrepit house nearby, which he’d like to fill with more creations) and into a quiet street that I remember how he might appear to the outside world.

Two men pass with swift sidelong glances. Looking but not looking, Frog King calls this visual ripple of the eyes. At the stop, he courteously waits – a patient figure from an opera or a fairy tale – until the minibus arrives. As I get on, heads of passengers turn to watch him walk away, back into his glade.

It isn’t exactly a happening, but it is definitely a moment.

An exhibition of Frog King’s recent works will on display at 10 Chancery Lane until January 11.