The first Chinese-built railway, the enthusiast trying to save it and his hero, the ‘father of China’s railroad’

As China forges ahead with a high-speed rail network few can rival, it seems hard to imagine it took 21 years for suspicious Qing dynasty officials to approve its first domestically built railway. An enthusiast tells of his fight to preserve it

It’s a little after 6am when the sun rises over Changping, a nondescript district in the northwest of the expansive Chinese capital. Flanked by the Mangshan hills, which form a natural limit to Beijing’s urban sprawl, Changping North railway station is small and devoid of distractions. With no cafeteria or convenience store in which to kill time, I settle myself in the spartan waiting room and stare at the clock. Most of my fellow travellers are asleep or fiddling with their smartphones.

Eventually, a green train with a yellow stripe along its flank – No 1458, from Changping North to Zhangjiakou South – slides into the station. I board, find my third-class seat and wait for the engine to shudder back to life. We depart at 6.46am, navigating the last tumbledown extremities of the city before concrete is replaced by jagged hills and steep ravines.

As the red East Wind locomotive hauls the train towards the Badaling section of the Great Wall, we pass old stations – many no longer in use, and all crumbling testimony to the longevity of this particular line. It’s impressive to be on a train negotiating such dramatic topography. Knowing that the line was completed in 1909, and that it was the first of its kind, designed and built solely by Chinese hands, makes the journey extra special.

After reversing the direction of travel twice – a technique known as zigzagging, and employed to negotiate steep gradients – the track eventually leaves the mountains for a vast plain that is coloured 50 shades of brown. This is a land of pig farms, of grazing goats and horses and of single-storey brick compounds with gardens littered with plastic rubbish. On this side of the Great Wall, the “Chinese dream” is largely an abstract concept.

Some young railway enthusiasts are busy photographing and filming, stirring the elegant woman seated across from me into accosting the ticket inspector. “If this is the last time this train will ever run,” she asks, “how will I get home in the future?”

“Take another vehicle,” the railwayman replies gruffly.

The sight of heavy industry – no longer permitted in the capital – announces our arrival in Hebei province, and we pass beneath pillars that will support the Beijing-Zhangjiakou railway when it is completed two years from now. The new line will connect the two cities in about 50 minutes, making the Qing-dynasty hunting grounds more easily accessible for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. (The district of Chongli, directly to the north of Zhangjiakou, is renowned for its snowboarding.)

Essentially, this relatively poor region is now looking ahead to future prosperity. I can’t help but look back down the line, however, to the men and the events that forged China’s first home-grown railway.

The story of the Jingzhang railway begins in 1872 – and not in northern China, but in North America, to where 120 Chinese boys, with an average age of 12, were sent by reform-minded officials to be educated in Western ways and ideas. This remarkable (if ultimately frustrated) initiative, aimed at re-firing the furnaces of the moribund Qing empire, produced an alumnus of talent, many of whom, as Liel Leibovitz and Matthew Miller write in their non-fiction book Fortunate Sons (2011), ultimately “led China during the final days of its empire and attempted to shepherd it through ambitious reforms”.

After crossing the Pacific by steamship, and while passing through California en route to school in New England, the youngsters were exposed to many modern technological marvels, including multi-storey buildings and electric lights. But, as Leibovitz and Miller note, “What interested them most during their brief visit to San Francisco was the railroad station […] For the boys, the story of the railroad’s creation could have contained many lessons about the contrasting outlooks of imperial China and the young American republic.”

It may be hard to believe today, with China’s high-speed network stretching 25,000km, but the country was a late convert to the virtues of rail. The Qing court was wholly unimpressed with “barbarian inventions” from overseas, which they feared would disturb ancestors sleeping in their graves.

Though Chinese toil helped build America’s transcontinental railway (completed in 1869), as well as Russia’s enormous Trans-Siberian railway (ready in 1916), the Germans, Americans, British, French, Russians and Japanese were largely responsible for – and chief beneficiaries of – China’s stunted rail network.

Following a humiliating defeat in the first Sino-Japanese war, in 1895, it dawned on China’s rulers that their conceited world view had rendered the Celestial Empire impotent when confronted by steam-powered nations. The foreign railways snaking through China were a clear sign of the country’s weakness and the state of semi-colonialism that aroused resentment in the provinces, culminating in the Railway Protection Movement, which called for the domestic development of railways.

Among the boys sent from China to New England was 12-year-old Zhan Tianyou (also known by his Cantonese name, Jeme Tien-yow, or simply as Jimmy). Born in Guangdong, Zhan would prove to be one of the most brilliant students in his class, particularly in mathematics.

On returning to China in 1881, however, Zhan and his Westernised classmates were mistrusted by Qing officials, and many were posted to remote locations. Zhan was sent to the coastal port city of Foochow (now Fuzhou, in Fujian province) to work for the imperial navy.

Having been inspired in the United States, he eventually realised his dream of becoming a railway engineer in 1888, at the age of 27, when he was enlisted to work on the line running between Peking and Mukden (Beijing and Shenyang, respectively).

As a result of the Railway Protection Movement, provincial governors were permitted to build railways. Some functioned well, but others soaked up funds and went bankrupt, causing the imperial government to nationalise the network. The move provoked civil unrest that fed into the 1911 revolution, which ultimately toppled the Qing dynasty.

When the child emperor Puyi abdicated, in 1912, the curtain was brought down on more than 2,000 years of imperial rule, in part because of China’s awkward relationship with the railway.

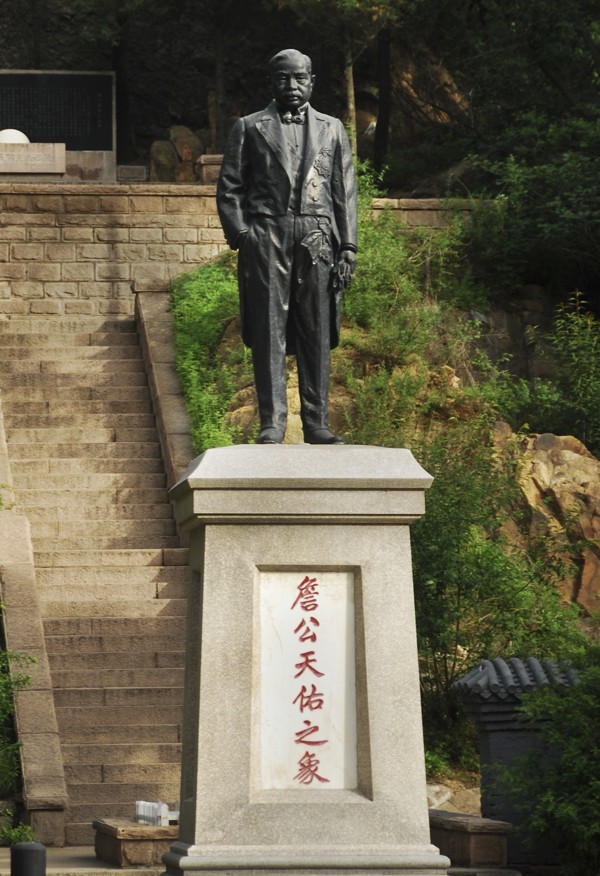

Zhan continued to engineer railways during the Republic of China’s early years, including the Szechwan-Hankow-Canton (Sichuan-Hankou-Guangzhou) Railway, from 1912 to 1918. His skills earned him the posthumous title “father of China’s railroad”.

Zhan Tianyou is my hero. He did things most of us will never manage to do. Of course, selecting a hero is a personal choice, but these kids that idolise singers or entertainers … to my mind, they’re quite pitiful

Roll forward to the 21st century: the world’s second largest economy is a leader in railway technology, which it aims to use in expanding its influence abroad via the “Belt and Road Initiative”. Recent headline-grabbing developments have included a goods train that travelled from Yiwu (in Zhejiang province) to London in January last year; a high-speed “Silk Road” railway linking Baoji, a city in Shaanxi province, with Lanzhou, the capital of neighbouring Gansu province, opened in July; and a high-speed railway that has connected Xian, Shaanxi’s capital, with Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, since December. The route punches through terrain that Tang-dynasty poet Li Bai described in the eighth century as “harder than the road to heaven”.

But while China’s impressive network frequently attracts superlative after superlative, one young Beijinger is gazing back to what he nostalgically calls “railway culture”, which he believes is fast fading.

Wang Wei and I first meet in Zhejiang, in the amber-hued autumn of 2017, while attending the Lishui Photography Festival (November 15-19). On day two of the gathering, art critic and curator Bao Kun accosts me over the hotel breakfast buffet, asking, “You’re always riding around China on trains, right? Well, why don’t you check out Wang Wei’s exhibition?”

Having long been a fan of veteran photographer Wang Fuchun’s series of images of Chinese passengers on trains, taken over the final three decades of the 20th century, as well as Shanghai-based Wang Lu’s beguiling railway landscapes, I head off to find yet another Wang who is training his lens on … well, trains.

Wang Wei’s exhibition, titled “My Jingzhang Railway”, is housed in a repurposed Mao-era oil pumping station. A tall twenty-something sporting a Chinese train driver’s hat and who speaks Mandarin with a deep voice and a strong Beijing accent, Wang’s pictures take me on a journey through China’s railways, past and present.

If I can get people to look at railways in a different way, that’s enough for me

“I was raised near Xizhimen,” Wang explains, describing the area where Beijing’s ancient West Gate once stood. “There was a railway station there that was still active in those days. So you could say I was raised by the iron road.” He shows me a picture of himself as an infant, standing on railway tracks. “I consider it a great privilege to have grown up there.”

Wang’s primary school was also next to the railway.

“Sometimes we walked home on the tracks,” he says. “Then I went to Beijing No 19 Middle School, which, coincidentally, was where Zhan Tianyou was buried before he was exhumed and moved to Qinglongqiao railway station in 1982.”

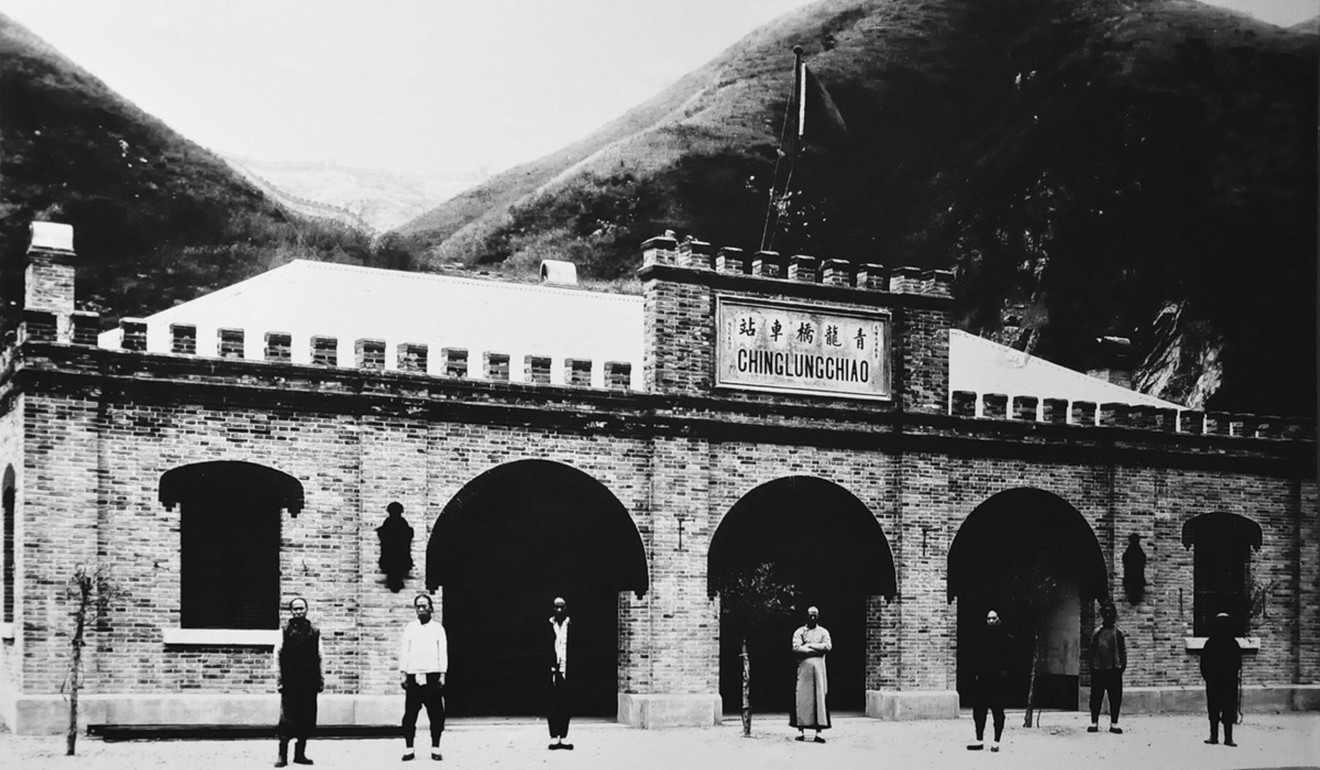

Today, that station, which nestles close to the Great Wall, is also a museum dedicated to the Jingzhang line.

Progressing to studying multimedia arts at university in Beijing, Wang says he “wasn’t very interested in the classes; the most important thing I learned was how to use Photoshop. However, I do recall one photography teacher, called Mr Xu, who told me I should photograph things that are disappearing. This inspired me to pursue railway-heritage photography more seriously.”

Wang had, in fact, been shooting the railway since the age of 11, with his family’s camera. “I was interested in the old stations, tracks and water towers that were immediately around me,” he says, adding that by the age of 16, magazines and newspapers were already buying his pictures. Aged 17, Wang started travelling further afield. “I went to Inner Mongolia, Qinghai, Yunnan and elsewhere, just to ride and photograph the railway. I never fly.”

After graduating in 2011, Wang took a job photographing property developments and financial institutions. He lasted two months.

People around me said that any endeavour that couldn’t be converted into money was useless, but I think money is no measure of the value of something

“I felt the work was utterly meaningless,” he says. “It was, I suppose, part of the process of moving from student to adult life, where circumstances are totally different. After that experience, I decided I would not go to any place to work. I’m not suited to the back seat. I need to drive my own destiny.

“People around me said that any endeavour that couldn’t be converted into money was useless,” he recalls. “But I think money is no measure of the value of something. Many of my old classmates would say things like, ‘If you don’t have a danwei [work unit], how will you support yourself when you’re older? These people aren’t even old, but they’re already dying. What a joke: to turn 20 and begin thinking about retirement.”

Wang documented railway culture as an independent photojournalist for three years, travelling all over China. His efforts paid off in 2013, when the China Railway Publishing House asked him to produce a book.

“Initially, I wrote one, My Jingzhang Railway, but then I found I hadn’t said all that needed to be said,” says Wang, who penned two more books over a four-year period. “The money wasn’t much, but if I can get people to look at railways in a different way, that’s enough for me.”

The young Beijinger’s enthusiasm is infectious, his achievements impressive, and I wonder aloud who has inspired him the most. “Zhan Tianyou is my hero,” Wang declares immediately. “He did things most of us will never manage to do. Of course, selecting a hero is a personal choice, but these kids that idolise singers or entertainers … to my mind, they’re quite pitiful.”

Wang and I catch up again a month later, a Siberian wind prompting the mercury in Beijing to nosedive into minus figures.

“I’ve found something interesting,” he tells me via WeChat. “Would you like to come and explore with me?”

And so we ride the subway together to Shijingshan district, on the western edge of the capital, and then hop on a public bus. Soon we are navigating ancient hutongs on foot, surrounded by crumbling tenements inhabited by low-paid migrant workers, many of whom are being evicted as part of Beijing’s efforts to cap its population at 20 million.

Eventually we find ourselves at Xihuangcun station, a lovely, single-storey, red-brick structure sandwiched between the old railway and a new high-rise community.

“I believe this was built during the Nationalist era and the facade was added during the Mao era,” Wang says, examining the rail-side lamps and old signage, even the gravel beneath the tracks.

Suddenly, a platform guard emerges and starts waving flags and blowing a whistle, as a gorgeous, blue-hued East Wind locomotive heaves into view ahead of several freight cars. Wang fires off salvoes from his Sony camera until the train is out of sight. “I hope I can get this station protected,” he says.

They didn’t have to build this. They just wanted to. High-speed trains are no fun. They’re not pretty and there’s no pleasure riding them

Even with the government’s appetite for demolition and development, Wang’s goal is not as crazy as it might sound: his interest in disappearing railway culture has made him a vocal advocate for conservation, with many successes under his belt.

“The first thing I got protected was the water tower in Xizhimen when I was 15 years old,” he says. “It was built in 1918 and was going to be pulled down. As I was a middle-school student, I felt I had no power to prevent it. Then, I had the epiphany to contact the media, so I got in touch with the Beijing Youth Daily.

They reported on it and some people from the China Railway Museum saw the story. It’s now conserved in [Beijing gallery district] 798.”

Five railway buildings have been saved by Wang, the largest being Beijing’s Qinghe station, which is now a registered cultural relic.

“I found it in 2015 and acted on the advice of a journalist friend, who told me that under Chinese law, anybody can make a request for a building to be protected. I submitted the forms to the Haidian district government and, in 2017, I heard it would not be torn down, which is great, though time will tell as to how they treat the building.”

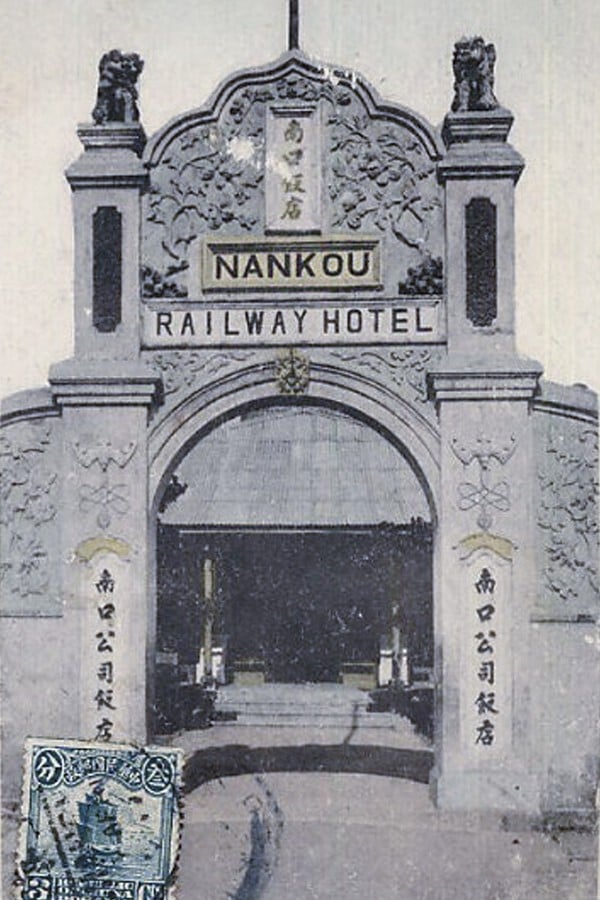

After Lunar New Year, Wang and I embark on several adventures together. We kick around the backstreets of Xikou, an old railway town turned suburb of Beijing, visiting neglected Qing- and Nationalist-era stations, and a railway hotel that was damaged during the Cultural Revolution, but which is now protected. We pay homage to Zhan, whose statue stands outside Qinglongqiao station, where some of the artefacts in the museum were donated by Wang himself.

It was Wang who recommended that I ride the final Jingzhang service, jumping aboard at Changping station last month. It is also springtime when Wang and I visit Qinghe station and find a massive new facility under construction nearby. It will serve the high-speed rail line between the capital and Zhangjiakou.

“They didn’t have to build this. They just wanted to,” Wang complains. “High-speed trains are no fun. They’re not pretty and there’s no pleasure riding them.”

Eventually, after much clambering up trees and hopping over fences, we reach the Qinghe station house, which is boarded off by a fence. Wang climbs onto some construction materials to get a better camera angle and soon bemoans some superficial damage to the station.

“Chinese relic protection is dreadful,” he grumbles. “It’s so inferior to developed countries. Sometimes, I lose all hope.”

I ask him if he’ll document the new railway station once it has been completed?

“No. I like old railways,” he says. “I’ll only photograph it when they pull it apart.”