Liu Xiaobo memorial a litmus test of protest fatigue in Hong Kong, where democracy movement is divided and disillusioned

A generation aroused by Tiananmen incident to fight for democracy locally and in mainland China no longer connects with young people focused on Hong Kong’s fate, and failure of Occupy Central sit-ins has dulled appetite for activism

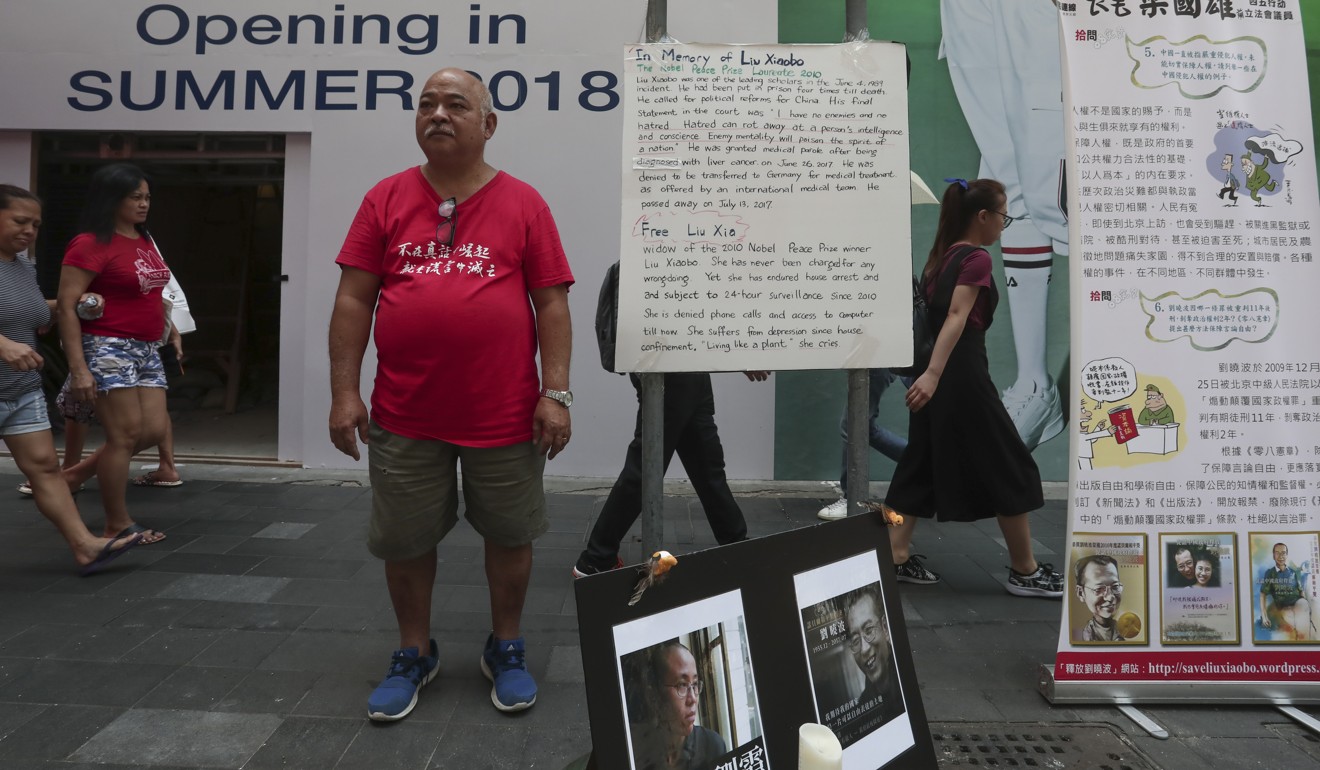

On a busy pedestrian street, one recent afternoon in Hong Kong’s Causeway Bay shopping district, sprightly Vivian – dressed in a black T-shirt, colourful shorts and bright yellow trainers – scans the crowd for anyone who might lend an ear. The 61-year-old smiles and waves amiably to shoppers. Behind her, fellow demonstrators man a street stand framed by banners announcing their cause.

“In Memory of Liu Xiaobo,” their message proclaims in large Chinese characters. “Set Liu Xia free now!”

Near the stand is a bronze statue of Liu Xiaobo, relaxing in an armchair. The late dissident and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who spent his adult life advocating for freedom of speech and democratic reform in China, died on July 13 last year, seven years into an 11-year jail sentence for co-authoring Charter 08, a manifesto calling for broad changes in China’s political system. Liu, too, was 61.

On this summer’s afternoon in early July, Liu’s widow, poet and artist Liu Xia, remains under guard in Beijing. She has endured eight years under house arrest without being charged with any crime.

With their home-made signs and placards, the motley band of volunteer activists, mostly middle-aged or older, stands out, incongruous among the shiny facades of nearby Michael Kors, H&M and DKNY boutiques. The group has been setting up shop in Causeway Bay every day since the end of May.

A few passers-by offer words of encouragement, some even donating money, or modest gifts intended for Liu Xia. But most ignore the activists. And, among those who do donate, some are unwilling to add their names to a petition calling for her release. Vivian understands their caution. For this article, the retired insurance adviser asks that her full name not be revealed.

A small minority of passers-by are hostile. On one occasion, rotten fruit was dumped outside the stand. On another, a can of milk coffee was poured over the statue’s head. Vivian and her friends have been accused of instigating on the behalf of foreign governments. One taxi driver shouted from his cab window, “Only Communist China can make Hong Kong strong.” He then got out of his car to repeat his angry words at closer proximity.

Vivian is not especially political herself, she says, but she believes the late Chinese activist should not be forgotten. “Liu sacrificed himself for his country,” she says. “This deserves discussion. We must talk about that.”

But does Hong Kong want to talk about Liu Xiaobo?

Is the fact that it is left to groups like this disparate collection of volunteers to keep the legacy of Liu Xiaobo alive telling of a mood of political futility, even burnout, among Hong Kong’s liberal-minded residents? And does the pro-democracy camp speak with a clear voice, or is it fatally fractured along generational lines, and between those who insist on peaceful protest and those who have expressed openness to a more radical approach?

For most passers-by, the stand in Causeway Bay barely registers. Vivian, who travels for half an hour by minibus each day from her home in Stanley, on the other side of Hong Kong Island, says she has meaningful conversations with perhaps a dozen people each shift. “Every day, I see many blank faces as people walk by,” she says. “But I do not believe this is the real story of Hong Kong. I believe justice is still in the heart of the people.”

Now in its 22nd year as a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong is often described as a tiny corner of freedom in a vast, authoritarian nation. But, with Beijing’s influence over the city rising, experts and activists claim support for the democratic cause is waning.

Four years ago, much of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy camp appeared united. The world watched as civil disobedience erupted across the normally passive territory, paralysing large swathes of the metropolis for more than two months.

The Occupy Central protests – also known as the “umbrella movement”, in a nod to the umbrellas protesters use to shield themselves from police pepper spray – began in September 2014 as a reaction to the decision by Beijing and the local government not to permit universal suffrage in Hong Kong’s 2017 chief executive and 2022 Legislative Council elections. Hundreds of thousands of people, from tram drivers and schoolteachers to pinstriped corporate lawyers, took to the streets.

Vivian, who had previously kept faith with China’s government, expecting the mainland to liberalise with its rising presence on the world stage, was among them.

By mid-December, however, the vast majority of protesters had left their encampments, the movement having elicited no concessions from China.

“After the Occupy movement, all street mobilisations in Hong Kong have suffered,” says Ivan Choy Chi-keung, a senior lecturer at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who specialises in local politics. “People have a sense of not being able to change anything.”

In university student unions, traditionally hotbeds of pro-democracy activism in Hong Kong, recent years have given rise to a different sentiment: a desire for Hong Kong to break with Beijing and pave an independent path forward. So-called localists have broadly rejected activism related to the Chinese mainland, in turn distancing themselves from established liberal organisations and leaving Hong Kong’s pro-democracy camp fractured along generational lines – the less able, some activists say, to effectively push back against the city’s pro-Beijing leadership.

“A lot of people, after the Occupy movements, have turned passive and find themselves at a loss for what to do,” says Ma Ngok, Choy’s colleague at Chinese University and an associate professor in the Department of Government and Public Administration. “They struggle to find effective means to express their dissatisfaction, and the general trend has been that there is less talk of politics in the city.”

“People feel disillusioned,” he adds, pointing to attendance at recent pro-democracy demonstrations as evidence.

In 2012, an estimated 5,400 Hongkongers marched on the central government liaison office in Sai Ying Pun to mourn the death in police custody of Li Wangyang, a prominent pro-democracy figure, in China’s Hunan province. When Liu Xiaobo died last year, just 2,500 turned out for a similar march. The circumstances might have been different – murder was suspected in Li’s case while Liu died of liver cancer that might have been treatable – but, for Ma, the disparity was telling, particularly given the fact that Liu was arguably the more well-known of the two.

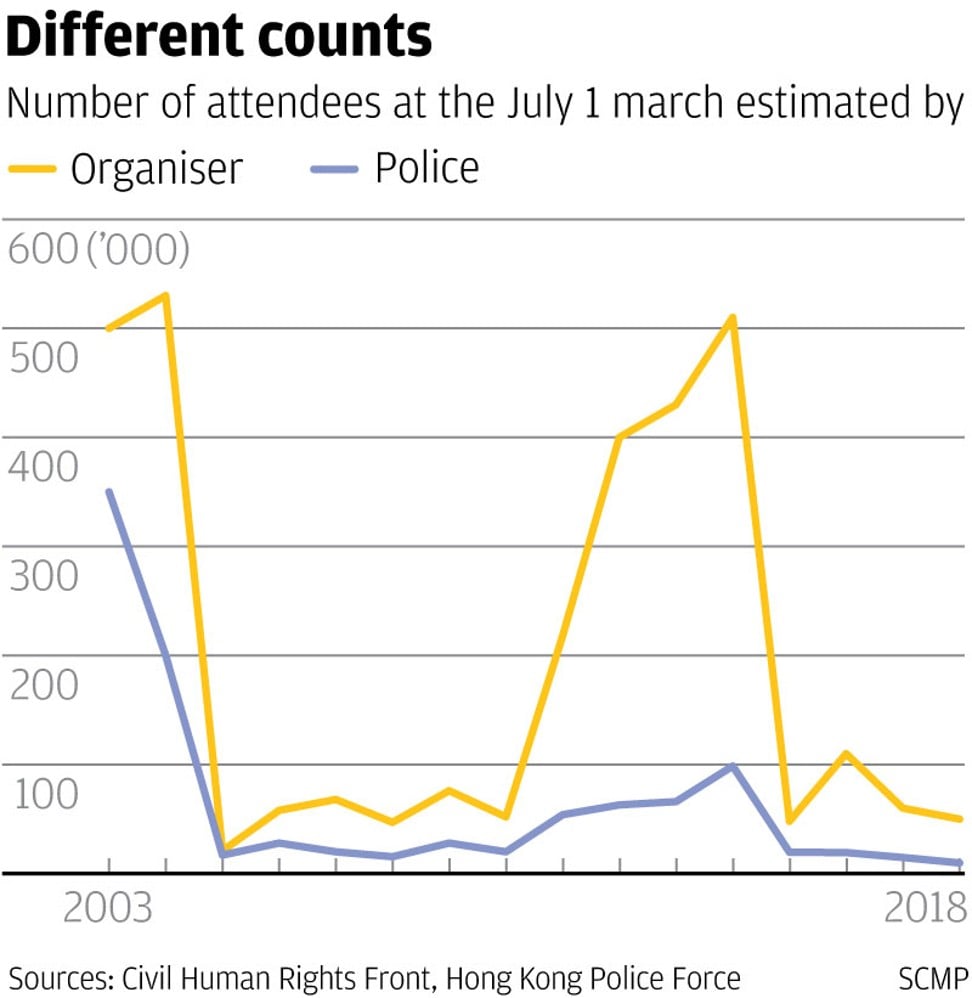

This year’s July 1 pro-democracy march, a protest staged annually on the anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to China, saw possibly its lowest turnout since 2003, when the demonstration first attracted sizeable public support. According to Hong Kong police, about 9,800 protesters joined the march this year – down from last year’s 14,500 and a far cry from the between 60,000 and more than 100,000 that police estimated took part each year between 2012 and 2014.

March organisers with the Civil Human Rights Front claimed a higher level of participation this year, saying that 50,000 attended, but even that number was lower than the same organisation’s estimates for previous years.

The reasons for the decline seem manifold, appearing to range from exhaustion in the wake of Occupy to self-preservation and acquiescence to Beijing. Hongkongers, some say, cannot be too careful with their political affiliations in times when booksellers specialising in material anathema to Beijing have gone missing, only to reappear apologetic on the mainland, and when pro-democracy activists repeatedly find themselves jailed in Hong Kong for violations of one statute or another.

When Vivian took part in Occupy, she was “utterly shocked” to find lifelong friends turning up their noses at her political zeal. A worried uncle and a brother advised her to tone down her rhetoric. While her husband has stood by her side in recent protests, the couple’s 23-year-old son has voiced concerns for their safety.

One volunteer in Causeway Bay, who asks not to be named, keeps his presence there a secret from his wife, adding that she would not be pleased. On the day coffee was poured over the statue, it was wiped away by a woman who regularly lays flowers at the scene, but who declines to share her name with the volunteers.

Experts say such caution, mixed with fatigue among democracy-minded Hongkongers, has created a profound disillusionment. Yet this only partially explains declining participation at protests, according to Choy. Equally responsible, he says, is a widening ideological gap between the generations.

For many of the youth, the Occupy movement has come to represent a failure of radicalism, Choy says. Their desire for rapid – many would argue, unrealistic – change has left peaceful methods such as those employed by Liu Xiaobo discredited in their eyes. Frustrated by the perceived ineffectiveness of traditional forms of protest, Hong Kong’s student unions have taken increasingly extreme positions, including calling for independence from mainland China and even proposing violence.

We know Hongkongers were once quite interested in these issues, but at that time Hongkongers thought of themselves as Chinese. Nowadays, we see ourselves only as Hongkongers and cannot be responsible for human rights in China

Pro-democracy groups such as the League of Social Democrats and the Civil Human Rights Front have traditionally been able to rely on the support of student unions. Today, the youth are taking a different path when it comes to matters such as Liu Xiaobo and the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown.

“We know Hongkongers were once quite interested in these issues, but at that time Hongkongers thought of themselves as Chinese,” says Au Cheuk-hei, the 19-year-old president of Chinese University student union. “Nowadays, we see ourselves only as Hongkongers and cannot be responsible for human rights in China.”

A June 2018 poll by Hong Kong University shows that just one in six Hongkongers aged between 18 and 29 are proud to be Chinese citizens, compared with one in three Hong Kong adults as a whole. Au complains that older generations of activists tend to ignore the sense of identity he and other youngsters associate with Hong Kong – and the alienation, not just frustration, they feel with regard to the mainland.

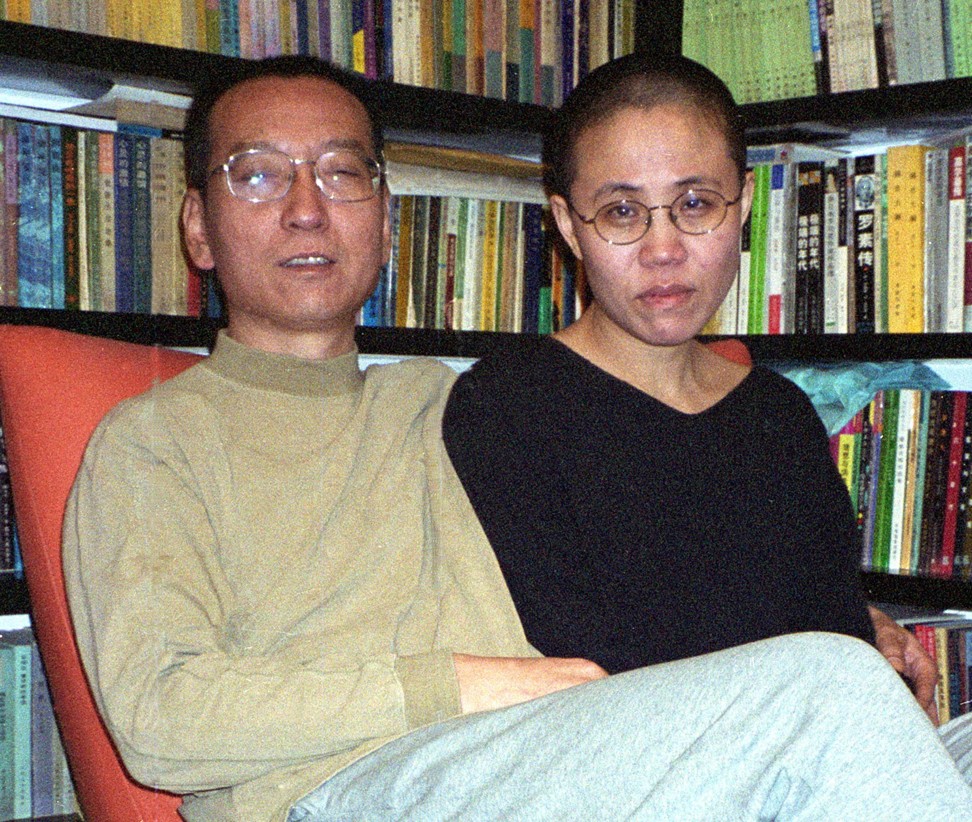

In 1989, Liu Xiaobo was already known in academic circles for his criticism of Chinese social and literary traditions. He was teaching as a visiting professor at Columbia University, in New York, when the protests in China broke out. He quickly returned to Beijing to throw support behind the students.

In the weeks that followed, Liu was steadfast in advocating non-violent protest. When the crackdown came, he negotiated between student and military leaders for the exit of thousands from Tiananmen Square, possibly preventing many more deaths.

Liu was arrested and jailed the day after the crackdown. It would be the first of four prison terms, as Liu continued to call for non-violent resistance to the Chinese Communist Party in the decades that followed. In 2010, during his final term, Liu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize – but in China news of the honour was censored in state-run media, and Liu was prohibited from attending the Nobel ceremony. On stage in Oslo, the Nobel committee famously presented the award to an empty chair. Liu has since become a mainstay figure of international pro-democracy activism.

“Liu Xiaobo represented and continues to represent peaceful opposition to a highly authoritarian regime,” says Sophie Richardson, China director for the international non-profit organisation Human Rights Watch. “He argued not just for his own rights but for the rights of all. That selflessness still resonates deeply for democracy and free-speech activists who hold Liu up as an exemplar of their movement.”

Indeed, Liu’s story featured prominently in this year’s candlelight vigil in Hong Kong’s Victoria Park, which is held annually on June 4 to commemorate the Tiananmen Square crackdown.

Student union leaders unanimously chose to forego the vigil, however. Many students also snubbed the July 1 pro-democracy march. Ken Lui Lok-hei, acting president of Baptist University student union, says that, in the view of students, demonstrations such as the vigil and the march are outmoded.

What’s more, 20-year-old Lui says Liu Xiaobo’s story does not resonate specially for him. Au, Lui’s Chinese University counterpart, suggests Liu is not as important an example to Hong Kong youth as Edward Leung Tin-kei, the 27-year-old who became a popular face of student activism following the 2016 Mong Kok riots. In June, Leung was sentenced to six years in prison for assaulting a Hong Kong police officer during that incident, which arose as a backlash against the government’s crackdown on unlicensed street hawkers during Lunar New Year celebrations. Leung’s sentencing might serve as a cautionary tale for young Hongkongers who are proponents of violent resistance, but Lui instead cites Leung’s case as an inspiration.

“The traditional ways are non-violent and peaceful,” Lui says. “But to fight for democracy in Hong Kong, every effective measure must be taken, if necessary.”

At 41, Ng straddles the generational divide between the students and the elder activists who dominate the pro-democracy camp. Though he is critical of many of the students’ views, he also acknowledges that rhetoric on both sides of the divide tends towards extremes, especially in the lead-up to elections. The division, Ng says, is harmful to the goal of both groups for a freer Hong Kong. As long as the divide persists, he says, it will limit their ability to counter the city’s pro-Beijing leadership.

Conservatives in government, meanwhile, view the premises of both camps as deeply flawed.

Holden Chow Ho-ding, vice-chairman of the city’s largest Beijing-loyalist party, the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, says that he supports the right to protest and is in favour of differences of opinion – which, he adds, are guaranteed under Hong Kong’s Basic Law. As a patriot, however, Chow says he views protests calling for changes in mainland China, including those memorialising Liu Xiaobo, with scepticism.

“Respect for ‘one country, two systems’ means we must respect the China we have,” Chow says, referring to the principle that guarantees Hong Kong’s political autonomy from the mainland through to 2047. Chow warns that criticism of Beijing implies disrespect for “one party, two systems”, which, in turn, might put the arrangement at risk.

“We do not wish to see people trying to antagonise the central government,” Chow says. “That is not conducive to the city’s economic development or livelihood.”

Fu Hualing, a law professor at the University of Hong Kong who specialises in human rights, reads the activists’ protests differently. In his view, advocacy for democratic reform in China is overtly patriotic.

“This work is a reminder to people in Hong Kong that we have this right to speak up,” Fu says. “It also sends a message to people in the mainland still fighting for their rights that they are not alone, that they have supporters in China who want the same thing they do.”

We have this statue here right now to try to remind people not to lose their conscience. If all of us take small steps together, it is possible to make a difference

Tsang Kin-shing considers himself a Chinese patriot. The 62-year-old activist and former Hong Kong legislator was born to mainland Chinese parents in the 1950s. His father, a successful entrepreneur, relocated the family from Guangzhou to Hong Kong for fear of persecution under Mao Zedong’s regime.

Tsang, known warmly by friends and former constituents as “the Bull”, a nickname that is a match for his sturdy build, has often incorporated art and props in his political messages. Both the stand in Causeway Bay and the bronze statue of Liu Xiaobo are his doing. The League of Social Democrats, of which he is a member, provided material support, including tables, a large black canopy and a loudspeaker that announces recorded slogans in Cantonese, Mandarin and English, blaring: “Mr Liu Xiaobo spent his life working for the democracy movement … He however received merciless suppression by the communist regime … Today, we want to continue the spirit of Liu and promote his ideas in a peaceful and rational way.”

Tsang does not view Liu’s case as separate from the cause of Hong Kong activism. He sees the writer and activist as an individual who “stood straight and tall”, even in the face of imprisonment, and as an enduring source of inspiration.

“We have this statue here right now to try to remind people not to lose their conscience,” he says. “If all of us take small steps together, it is possible to make a difference.”

The Causeway Bay protest stand was originally erected outside Times Square shopping centre on May 31 – in time, Tsang hoped, to provide support for the June 4 candlelight vigil. Tsang was joined at the stand by an assortment of volunteers, many of whom had met and forged friendships during the Occupy movement. Most, like Vivian, were unaffiliated to the League of Social Democrats and simply wanted to lend a hand.

Times Square, known for its high-end fashion stores, was chosen because it attracts a steady stream of visitors from mainland China, where censorship has seen to it that many are unfamiliar with Liu. Indeed, activists estimate that only half the mainlanders they have spoken with know about Liu. According to Vivian, some parents, who she and her colleagues assumed to be from the mainland, appeared to shield their children from the booth, or hurry them along as they passed by.

Within days, the management of the mall, which also administers the public space surrounding it, claimed the activists were in violation of rules that prohibit political activities and the use of loudspeakers on the premises. Tsang and the League of Social Democrats urged the company to allow them to remain until July 13, the anniversary of Liu’s death, but Times Square threatened an injunction. Wishing to avoid a potentially costly legal battle, Tsang and his team relented, moving to nearby Paterson Street on June 19.

At the new site, Tsang describes his political work as a labour of love. While some parents try to protect their children by saving money, Tsang says it is more important to first save Hong Kong.

If we do not fight now, the fight will not disappear. It will only be pushed to future generations

Tsang was a father of two young sons in 1989. The deaths of student protesters in Tiananmen Square that year proved his political awakening. In the 1990s, Tsang was elected to both the District Council, representing the Lok Hong constituency in Chai Wan, and the Legislative Council. He later founded pro-democracy radio station Citizens’ Radio, which is subject to frequent government fines and penalties for, among other transgressions, operating unlicensed equipment.

Throughout his political life, Tsang says he has been driven by a desire for his children, now in their 30s, to live comfortably and unfettered by struggle in Hong Kong – and perhaps even for them to raise their own children in the city, rather than moving abroad, as is the increasing tendency among young parents in the territory.

“I believe in insisting on the value of society, making sure my children have a better place to live – that is love,” Tsang says.

Avery Ng, who has a two-year-old niece, says he, too, is driven by the ideal of securing a future for Hong Kong’s young. “If we do not fight now, the fight will not disappear,” Ng says. “It will only be pushed to future generations.”

Both men acknowledge the difficulty of appealing to Hongkongers amid changes in the city that can make their efforts seem futile. But both also see their work as necessary, and Tsang points to the small kindnesses of passers-by as reason for hope. Despite the criticism and setbacks, people have brought water and fruit for the volunteers on hot days. And while many mainlanders choose to avoid their message, Tsang happily recalls one elderly gentleman who approached the volunteers to show them the wallpaper on his smartphone: a picture of an empty chair.

On the morning of Tuesday, July 10, Liu Xia is released from house arrest in Beijing and put on a flight to Helsinki, Finland, en route to Berlin, Germany, where she will receive treatment for severe depression.

Her freedom is the result of high-level negotiations between the Chinese and German governments, but Ng, of the League of Social Democrats, argues that localised protest movements – whether in Hong Kong or London, Berlin or New York – similar to the one in Causeway Bay, kept Liu Xia’s case in the public eye, and had influence internationally.

The Causeway Bay demonstrators, coincidentally, already had a press conference scheduled for the day, but now, instead of issuing calls for Liu Xia’s release, they call for rounds of applause.

Using a microphone to address the small crowd, Tsang says the 10,000 or so signatures collected from the public in recent weeks, originally intended for delivery to authorities in Beijing, will instead be sent to Liu Xia, along with donated gifts. These include a painting and a poem, from a local father and daughter, and a work of calligraphy by a 94-year-old man who had travelled for more than an hour to visit the stand.

The general mood among the activists is positive, though some warn that Liu Xia’s release does not constitute a new political narrative: hundreds of human-rights lawyers and dissidents are still in custody on the mainland.

Three days after the press conference, on the anniversary of Liu Xiaobo’s death, the statue is transported the few kilometres from Causeway Bay to a public park on Victoria Harbour, in the shadow of the towering Hong Kong government headquarters.

That evening, under light rain, some 300 people gather in the park to take part in a vigil organised by the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, an affiliate of the League of Social Democrats. Candles are lit, speeches are given and songs are sung. Video clips highlight landmark moments in Liu Xiaobo’s life: his activism, his imprisonment, and a Nobel Prize notoriously being presented to an empty chair; Liu’s failing health, Liu Xia at his side in his final days, and his ashes being scattered at sea. Further videos show Liu Xia crying in her home in Beijing – and later disembarking from her plane in Helsinki.

As the 90-minute ceremony draws to a close, the rain picks up and the crowd becomes a canopy of umbrellas, recalling the Occupy protests of 2014. At the urging of one speaker, attendees raise three fingers in the air to symbolise “fight, freedom, and hope”. Another speaker calls for the release of Chinese dissidents and an end to one-party rule. Attendees finally gather around the bronze statue of Liu to leave flowers and their candles at its feet.

As the park empties, Tsang stands at the exit with a microphone, urging people to sign a large green tarpaulin he had spread out and intends to package with other items being sent to Liu Xia. With notes of encouragement, the tarpaulin’s surface is all but full.

Sculpting Liu Xiaobo

Soon after Liu Xiaobo’s death, on July 13, 2017, veteran Hong Kong activist Tsang Kin-shing teamed up with local political cartoonist Zunzi to design a life-size bronze statue of the late Chinese dissident. Hoping to avoid high production costs in Hong Kong, where artisans quoted more than HK$350,000 (US$44,600), Tsang says he commissioned a sculptor in Hunan province, communicating through an intermediary, who requested just 50,000 yuan (US$7,377).

After handing over a 10,000 yuan deposit, however, Tsang says contact was lost with the sculptor. He adds that he was informed by his intermediary that mainland authorities had paid the artisan a visit, confiscating his tools and materials. Tsang then looked to Taiwan, but he was quoted prices as high as those in Hong Kong.

Come March of this year, with time running out before the first anniversary of Liu’s death, Tsang resigned himself to a more modest tribute: a plaster bust of Liu, which he designed in collaboration with local sculptors. Two months later and at a cost of HK$10,000, the bust was ready.

After the activist cohort set up their demonstration stand outside the Times Square shopping mall, in Causeway Bay, on May 31, a friend of Tsang’s arrived with a photo. It showed a bronze sculpture of Liu Xiaobo, exactly as Tsang had originally envisioned it.

His design, Tsang says, had somehow made its way to an anonymous Hong Kong artist who took it upon him or herself to create the statue, which had a production cost of HK$170,000. Tsang says the statue was technically donated to the activists but they have sought to recoup the artist’s costs with donations at the stand.

The statue was delivered to Tsang anonymously – he says he still does not know the sculptor’s identity – and unveiled at Times Square on a cloudy Tuesday in the middle of June.

In the statue, Liu is depicted sitting in a chair, one leg casually crossed over the other. A slight smile graces his face, and in his right hand he holds a cigarette. One passer-by complained to Tsang that the cigarette might set a bad example for children. Tsang argued that the late dissident – who smoked – had suffered a hard life and deserved a break.

“When the Nobel committee awarded him the prize, the diploma was placed on an empty chair,” Tsang says later. “So now I want him to be comfortable, to sit down on his chair and cross his legs. I want to treat him to a cigarette.”

“I hope peace can be with him, even in his death,” Tsang adds.

Since July 13, Tsang and Avery Ng, chairman of the League of Social Democrats, have wondered what to do with the statue. It certainly could not stay in the park outside the Hong Kong government headquarters after the vigil. And it is unlikely that private or commercial spaces in the city will want it. “Not unless they want to go out of business,” jokes Ng.

Perhaps it could be sent abroad? But where? And how? Maybe one of the universities will take it, Ng says. Then again, he adds, even they are not the bastions of free speech they once were.

Additional reporting from Dorothy Ma