200 years to go before Laos is cleared of unexploded US bombs from Vietnam war era

- In the world’s most heavily bombed country, 20 million UXO have been cleared in the 45 years since clandestine US war ended

- That leaves another 80 million still to be dug out and defused, if foreign governments continue funding the work.

Thanksgiving is an American tradition that is unknown in most of the world. Fifty years ago, however, it landed in Laos, the small, impoverished Southeast Asian nation that was to become perhaps the longest-suffering casualty of the United States’ war in Vietnam.

Thanksgiving is held on the fourth Thursday in November. In 1968, that fell on November 28, and on that day, at the height of the war and on the orders of president Lyndon B. Johnson, turkey dinners were helicoptered in to American soldiers who were on a mission to sever the Ho Chi Minh Trail – the network of paths and tracks that constituted North Vietnam’s military supply lines to the south of the country – that ran through eastern Laos.

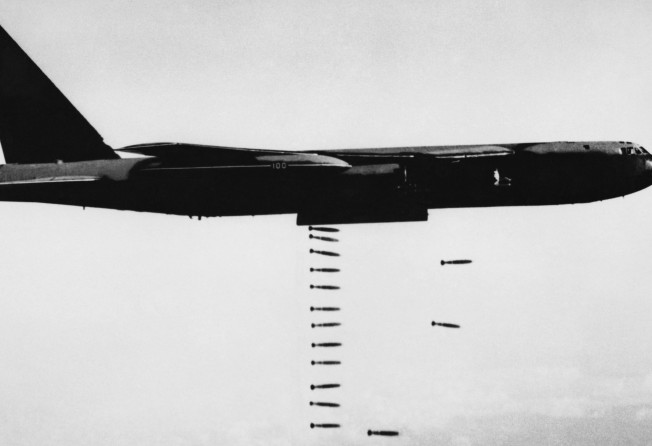

LBJ’s festive dinners were flown in at the same time as the US began dropping millions of bombs on the trail, which it had already been targeting for four years. Half a century later, Laos is still dealing with the deadly legacy of that bombing campaign, which left an estimated 100 million pieces of unexploded ordnance on the ground.

On a dusty dirt road near the sleepy southeastern Laotian town of Xépôn, just 20km from Route 909, which follows one of the Ho Chi Minh Trail’s main arteries, and 46km (29 miles) from the border with Vietnam, the day begins with a warning.

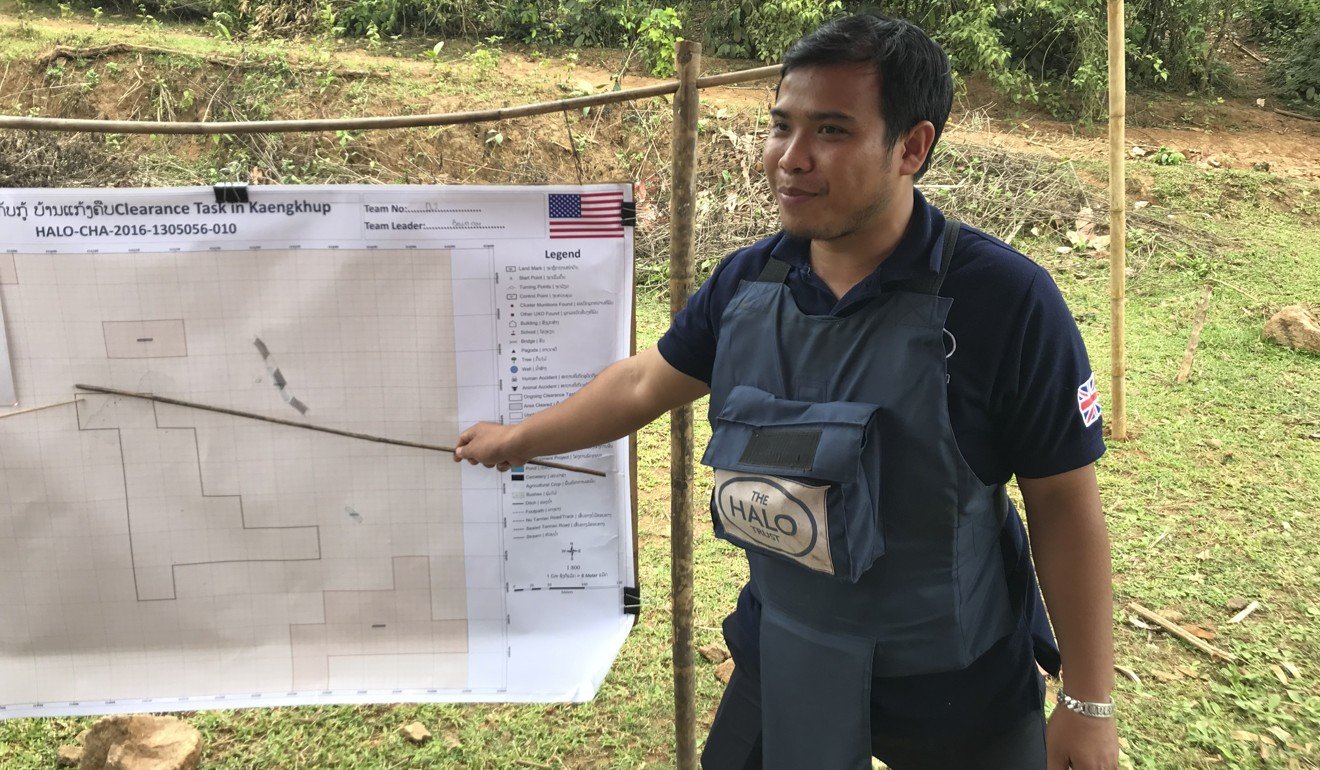

“Minh, remember, no metal,” says Calum Gibbs, a burly young Scotsman and an operations officer with the Scotland-based Halo Trust, one of several NGOs helping to clear up unexploded munitions left by the nine-year US campaign of aerial attacks on Laos, which ended in 1973. “There’s metal in your tape measure.”

Minh is a lean Laotian man, his skin like leather, trained by Halo as an unexploded ordnance (UXO) disposal expert. He sheepishly hands his tape measure to colleague Gah, then disappears into the forest to re-examine a bomb found by villagers. A Halo team has already tried, unsuccessfully, to destroy the weapon.

Gah explains that taking metal close to the still-active fuses on some munitions could cause them to detonate. “The most dangerous ones are very sensitive – sensitive to temperature or with a fuse activated by magnetism,” he says.

As we mill around beside our four-wheel drive, Minh is somewhere among the trees, checking how much explosive is left in the weapon after the first attempt to render it harmless. Ten minutes later, he returns. “From the fuse, there’s 45cm of high explosive,” Minh says. “The parts that are left are quite thick metal, so we cannot burn a fire to detonate it. This bomb is quite big – 500lb.”

“So … Plan?” Gibbs asks. “Destroy it?”

Minh will calculate the area that will have to be taped off before the bomb can be detonated. For the disposal of a 500lb bomb, Halo advises that no people or livestock should be within a 1.5km radius. That distance can be reduced by using earthworks, sandbags and walls, but the road we are standing on is well within the blast zone. It will have to be closed off.

Gibbs gestures towards a pile of sandbags at the top of the riverbank that he says was part of a protective bunker. “This was our firing point when we blew the item initially,” he says. “A 1.5km firing cable is not very practical, so you have a bunker that you build inside the blast zone, with a certain number of sandbags over the top, nice and secure from frag.”

Bunkers, road closures, dozens of Halo staff to seal off the blast zone, kilograms of C4 explosive, hundreds of metres of firing cable and the constant risk that something might go fatally wrong – all to get rid of a single large bomb. And the US dropped close to 300 million on Laos!

As troops’ turkey dinners were being choppered in that November, the bombing campaign was being massively ramped up, from about 4,700 sorties in October 1968 to some 12,800 the following month. In total, the US launched about 580,000 bombing missions over Laos – equivalent to a planeload of bombs every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, for those nine years – making it the most heavily bombed country per capita in history. It has been estimated that possibly one-third of the devices failed to detonate, and as many as 80 million remain unexploded. They litter villages, tracks, farmland and forest across much of the country. At the current rate of progress, making Laos completely safe again will take 200 years.

Nevertheless, progress has been made. When I visited Xépôn 20 years ago, it was a ramshackle collection of small houses and huts with no electricity. Route 909 was hardly a road at all. Deadly explosives lined the dusty, cratered track and many more unexploded munitions – mainly cluster bomblets – lay in wait in fields for unlucky farmers and other villagers.

Today, the Route 909 section of the Ho Chi Minh Trail near Xépôn is a smooth, two-lane blacktop along which American-made trucks thunder. Power lines that did not exist two decades ago follow the road. There is a tidily maintained war museum, and fishermen’s canoes in the Xépôn River have been fashioned from the discarded long-range fuel tanks of B52 bombers.

Further north, in the province of Xiangkhouang, where British bomb-clearance NGO Mines Advisory Group (MAG) has been working for 24 years, the story is similar. In the provincial capital, a small town named Phonsavan (where, two decades ago, it seemed that every house incorporated bomb casings and panels from aircraft), main roads are paved and tidy, shops and other businesses have sprung up, and there are street lights where once there was no electricity after 10pm.

Upgrading major roads and providing electricity has been a priority across the country, and UXO clearance resources – of both government and private contractors – have been committed accordingly. The discovery of precious metals and minerals in the Xépôn area has attracted foreign companies, which has led to the stepping up of bomb-clearance efforts around those projects.

When it comes to land that local people have to live and work on, however, clearance has, in the main, been left to NGOs such as Halo, MAG, Norwegian People’s Aid and Japan Mine Action Service.

“We prioritise our clearance based on impact and beneficiaries, so we can clear an area that’s going to be used for [crop] cultivation or a school,” says Gibbs. “In one of the villages we drove through earlier, we cleared an area and they built a school on it. That’s exactly what we want.”

Gibbs emphasises the importance of education in keeping people safe. “We send out risk-education teams to educate kids,” he says. “They have a UXO song and the kids sing it so they remember that UXO are dangerous.”

Victims of the explosives scattered across Laos are, in fact, disproportionately young. “On my second day in the country, there was a fatality, an eight-year-old,” Gibbs says. “They looked like they’d been throwing it around. They’d found it in the forest.” He remembers the offending explosive as being a BLU 24 cluster bomblet, which is the size and shape of a tennis ball. “One kid died, one was severely wounded, and three young girls suffered blast fragmentation injuries.

They’ve lived with it for so long – their parents, their grandparents – it’s a feature of life. It’s almost like they’ve just become normalised to it, which is really sad

“I remember what I was like as a kid,” says Gibbs. “If I grew up here, I’d be playing with this stuff. You see an iron-looking ball and it’s something to throw at your mates.

“We get out and … show pictures of these things to kids, but I remember what I was like at school, and when someone comes in to teach you about whatever, you’re playing with your mates and talking about football. They’ve lived with it for so long – their parents, their grandparents – it’s a feature of life. It’s almost like they’ve just become normalised to it, which is really sad.”

Thanks to NGOs’ education efforts and continuing clearance, casualty rates are declining, down from about 200 deaths annually two decades ago to 50 or so in recent years. “The figures I’ve seen show 50,000 casualties since the war ended in terms of UXO accidents,” Gibbs says. “Because now most of the urban areas have been cleared, they’re getting less and less, but as the population expands and more areas are cut for upland [rice] paddy and that sort of thing, people are going to be interacting with UXO more and more.”

Minh says that Halo’s survey teams receive about 60 call outs every month for UXO discovered by villagers, and that its disposal experts destroy 70 to 80 explosive devices a month. As unused land is earmarked for development, however, Halo is in a race against time. The work is hard, dangerous – and excruciatingly slow.

All of which is demonstrated when we accompany a clearance team, sweating under body armour and ballistic goggles, up a steep hillside and through thick undergrowth on a banana plantation. About 200 metres (650 feet) in, we come across a marker of blue spray paint surrounding a BLU 26 cluster bomblet, which is on a list of items to be destroyed in a controlled blast later in the day. Such bomblets are the most prolific killers among the UXO in Laos.

Our next stop, after a bone-shattering drive up a rutted track, is on a hillside where an area perhaps the size of a football field has been stripped of vegetation to allow clearance workers to use metal detectors. It has taken eight of them a week to defoliate and survey the area, during which eight live cluster bomblets and a larger bomb have been discovered. More are suspected of being buried under the surface.

Detectors wail with alarming frequency as we slog up the slope. Each time, a hole is dug in a fixed radius around the locus of the signal, and whatever lies beneath the soil is identified. Usually, it turns out to be shrapnel, but every signal must be investigated. Fragments are removed from the area – nothing that can set off a metal detector should be left behind.

Fortunately, there have been no casualties among Halo’s survey and clearance teams. What’s more, jobs at the NGO are highly sought after by locals, and Halo is now preparing to boost its headcount in Laos from about 330 to 550.

“We’re only just starting interviews, and we might have 2,000 people turn up,” Gibbs says. “Everyone wants to work for Halo because it’s international NGO money, and it’s job security and stuff like that, even though it might well be that it’s just for a year.”

That’s always a difficulty – the funding is at the whim of politicians. They might decide this year that their priorities are going to be different to appeal to voters. Few politicians see beyond their term in office

In a country where most people get by on less than US$2 (HK$15.50) a day, an NGO job represents a lucky break, even if employment can be cut short by the stroke of a pen in Whitehall or Washington.

The vast majority of Halo’s funding in Laos comes from the British and American governments, and the NGO received a significant shot in the arm for its operations there when US president Barack Obama, in his final months in office, in late 2016, pledged to double his country’s US$45 million contribution to UXO clearance in the country. That was a three-year commitment.

“Some governments get really involved in the mine-action sector, and it waxes and wanes depending on who’s in charge,” Gibbs says. “That’s always a difficulty – the funding is at the whim of politicians. They might decide this year that their priorities are going to be different to appeal to voters. Few politicians see beyond their term in office.”

The precariousness of funding is a frequent topic of conversation in the UXO clearance community in Laos, and unrealistic clearance targets expected by international donors can be a source of frustration.

“Because the targets are almost unattainable, there’s every chance that the government department involved will turn around and say, ‘Well, you failed to meet your targets, so we’re not going to give you the money again,’” one foreign NGO worker says, adding, “It won’t be me that suffers, it’ll be the local staff.”

While employment by a foreign NGO lasts, locals benefit from not just attractive pay, but also professional training. And although they are digging on their hands and knees in the stifling heat, and do face genuine risks, as Gah explains, “they feel they’re doing something good – something good for their country”.

The population of Laos has grown rapidly, from 3 million in 1975, when the ruinous Vietnam war finally ended, to close to 7 million today. With a median age of about 21 years, Laos has the youngest population of Asia, it is believed, so the overall fertility rate is high and numbers are predicted to continue rising. With ever more mouths to feed, the need for more land to grow crops on also rises, placing more people in danger.

“During rice-growing season,” says Gibbs, “everyone’s out and they’ll find more items, so we’ll get more calls.”

Harvest season in Laos (which at the time of writing was well under way) also brings increased UXO-related risks. As Americans tuck into their Thanksgiving turkey dinners on November 22, just like the US troops in Southeast Asia half a century ago, Laotian people, especially those in the rural areas that were devastated by the US bombing, will be giving their own thanks – so long as the rice crop comes in without any more casualties inflicted by a long-ago war.