How Chinese video app TikTok conquered the world, making teens, and child safety, trend

- With more than a billion downloads, the short-form video app owned by start-up ByteDance has captured the imagination of users across the globe.

- So what makes TikTok tick?

Most nights, from around seven till midnight, Sydney Jade is on TikTok, the smartphone app of the moment. The platinum blond teenager films herself singing show tunes, doing jumping jacks and joking around with store clerks at a Walmart not far from her home in Oklahoma, in the United States. Her short music videos and live streams are popular – Jade has 284,000 followers, some of whom periodically send her virtual gifts, such as 99 US cent (HK$7.80) puking-rainbow stickers.

Jade’s parents resisted TikTok at first. They hadn’t heard of the app and, Jade says, “didn’t like the idea of strangers watching me sing alone in front of the pink curtains in my bedroom”. But she convinced them that TikTok was “friendlier for kids than other apps like Facebook”. They let her join last year, just as, it seems, every other teenager signed on as well. In January, TikTok was the most downloaded app in the Android and iPhone stores, according to research firm Sensor Tower.

The story sounds a lot like the rise of other social-media powers such as Instagram and Snapchat, both of which pitched themselves as alternatives to Facebook’s big blue app. But TikTok wasn’t created by Stanford University students that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg could buy off or spend into the ground. It is a subsidiary of a Beijing start-up, ByteDance, which has built a collection of apps in China powered by vast troves of data and artificial intelligence (AI). Last year, ByteDance’s investors valued the company at US$75 billion, the most of any start-up in the world.

Inevitably, especially in the age of Donald Trump, TikTok’s fast growth and Chinese ownership have made it the subject of scrutiny in the US. In March, a government body – the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) – ordered gaming company Beijing Kunlun Tech, which bought gay-dating app Grindr, to sell the business over concerns that Chinese intelligence agencies could potentially use data from the app to blackmail users. In an April 1 filing, the Chinese company said it was in talks with CFIUS. US authorities haven’t said they are investigating ByteDance in connection with its ownership, but the large user base could conceivably make it a target.

“Social-media platforms are increasingly considered sensitive by CFIUS,” says Farhad Jalinous, head of national security and CFIUS practice at Washington-based law firm White & Case.

ByteDance says it now stores all TikTok data outside China and that the Chinese government has no access. (The company’s privacy policy had previously warned users it could share their information with its Chinese businesses, as well as law enforcement agencies and public authorities, if legally required to do so.)

Separately, TikTok has faced concerns over privacy and child safety. In February, ByteDance was fined US$5.7 million by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to settle allegations that Musical.ly, which the Chinese company bought in 2017 and renamed TikTok, illegally collected information from minors. It was the largest FTC penalty in a children’s privacy case.

The settlement didn’t scare off ByteDance’s investors or the company itself, which is spending hundreds of millions of dollars to advertise on Facebook in the hope of luring away more users. Over the past three months, for instance, 13 per cent of all the ads seen by users of Facebook’s Android app were for TikTok, says app-analytics firm Apptopia.

The result is that ByteDance has had more success outside China than any previous Chinese internet company, including Baidu and Tencent. The TikTok app and its Chinese version, Douyin (“vibrating sound”), have been installed more than a billion times. Late last year, ByteDance executives told investors that they expect US$18 billion in revenue in 2019 and US$29 billion in 2020, according to people familiar with its finances who are not authorised to discuss the company publicly. ByteDance will “become a global player”, says Hans Tung, managing partner of GGV Capital, one of the company’s backers. “It’s just a matter of when.”

ByteDance’s Beijing headquarters, a former aerospace museum with 50-foot glass skylights, is a celebration of the company’s frantic pace. On a January afternoon, a video in the cafeteria asked workers to share New Year’s resolutions and regrets. Most seemed to involve workaholism. “To my ex, I’m sorry I was too busy at work,” one employee said. “I’m sorry to my kids that I’m never home,” another lamented.

The corporate culture is intense even by the standards of Chinese start-ups. Employee performance goals are published internally via a mobile app the company created called Lark and are reviewed every other month. In an interview, ByteDance’s senior vice-president for corporate development, Liu Zhen, mentions that founder and chief executive Zhang Yiming likes to travel to the West when the Beijing office shuts down during Chinese holidays. “So he can keep working,” she explains.

Zhang declined interview requests.

Now 36, he started ByteDance in 2012, in a flat near Beijing’s Tsinghua University. One of its first apps, Neihan Duanzi (“implied jokes”), used AI to tailor a selection of memes to individual users’ tastes. The effect was irreverent – think Reddit but grosser and more personal – and the app attracted tens of millions of users. ByteDance used the same approach to develop a news app, Jinri Toutiao (“today’s headlines”), which became China’s largest news site, with more than 700 million users. The success prompted acquisition offers from Baidu, Alibaba (which owns the South China Morning Post) and Tencent, all of which Zhang declined.

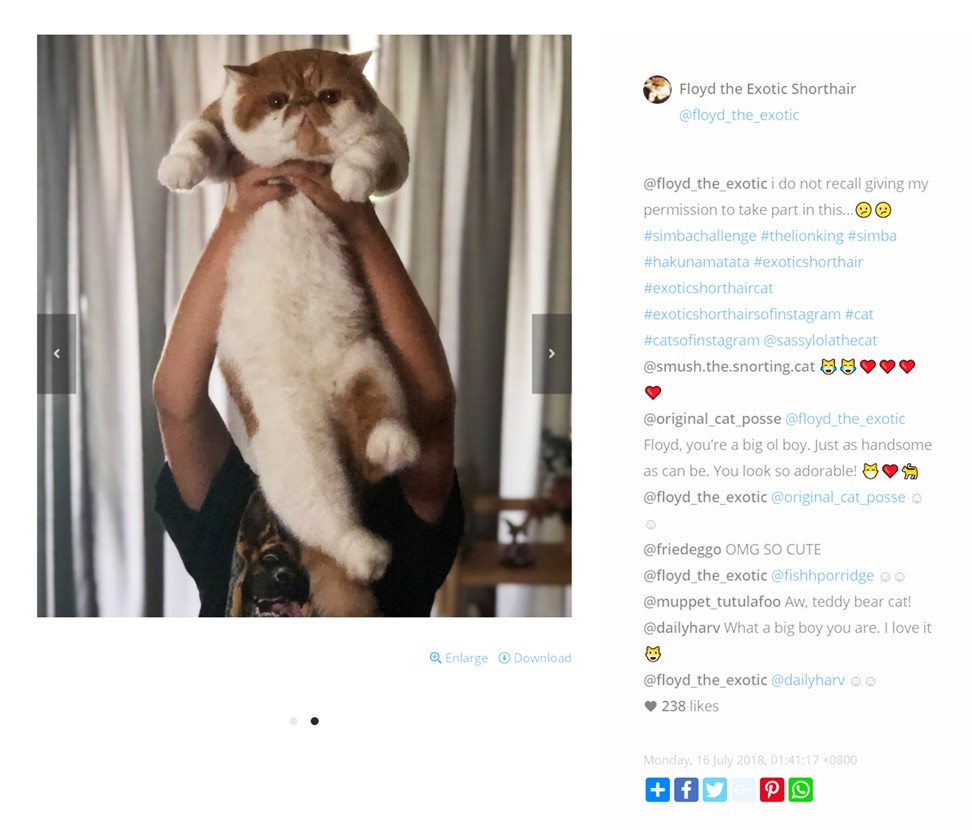

Then, in 2016, it launched a short-video app in China called Douyin, which allowed users to add music and animations. The following year, it created an international version, TikTok. Users who open TikTok are confronted with an endless feed of full-screen videos, generally set to music and no longer than 15 seconds, although it has experimented with longer clips. Tapping on a magnifying glass icon reveals TikTok’s “Discover” page, which displays a carousel of videos under “trending hashtags”: memes such as #potatoportrait, where users apply make-up to potatoes, and #simbachallenge, which ask them to re-enact an iconic scene from the movie Lion King.

Although these features make TikTok feel similar to Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat, the app doesn’t rely on social connections to figure out what to show you. Instead, TikTok decides what videos to show by tapping into data, starting with your location. Then, as you start watching, it analyses the faces, voices, music or objects in videos you watch the longest. Liking, sharing or commenting improves TikTok’s algorithm further. Within a day, the app can get to know you so well it feels like it’s reading your mind. That’s why Jade mostly sees videos of people dancing while her mother gets clips of dogs doing tricks.

Another way TikTok differs from big American social-media apps, which largely grew through word of mouth, is that its expansion didn’t happen entirely through the magic of viral marketing. Although the app initially took off in India and Southeast Asia, it struggled to attract users in the US and Europe. In November 2017, ByteDance paid about US$800 million for Musical.ly, a music video app that had more than 100 million users. A few months later, those users would find the app replaced with one bearing TikTok’s neon logo instead. The app suddenly had a substantial footprint in the US.

“Musical.ly believed in organic growth, and that worked great with early adopters,” says Tung, who also invested in the music-video app. “TikTok is based more on algorithm recommendations and paid growth”, meaning ads on Facebook and elsewhere.

Unlike on other platforms, where trends bubble up from users’ posts, many of TikTok’s trending hashtags are created by the company’s marketers. Ahead of its US launch, ByteDance hired about 40 social-media celebrities – including YouTube comedian David Dobrik – to make videos, paying each tens of thousands of US dollars. Some contracts required the influencers to ask their YouTube, Snapchat and Instagram fans to move over to TikTok.

ByteDance still makes most of its money in China, where its short-video app charges advertisers 15 per cent of what influencers get paid to promote brands. TikTok also takes a cut from the sale of digital coins that fans buy for creators during live-streamed videos.

In theory, relying more on professionally created content should make TikTok safer than Twitter or Facebook. But users say live streams are peppered with lewd acts and vulgar comments. That can be terrifying for children. Jade says she recently cut short a live appearance after commenters said they knew where she lived and threatened to kill her dog.

“It wasn’t real, but it could have been, and I got scared,” she says.

In February, a 35-year-old man was accused by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department of posing as a 13-year-old boy to send sexual messages to at least 21 girls on TikTok. Police said he showed up at the home of one of his alleged victims, a nine-year-old.

Three years ago, we were having a really hard time trying to pin them down and get them to do the right thing. They’re starting to be more responsible

In response to the FTC settlement, TikTok began requiring users in some countries, including the US, to input their birthdays, denying entry to the full-feature app to those who say they are under 13. It also started using facial-recognition software to identify youthful faces, expelling underage creators, and preventing younger viewers from seeing mature content.

It is too soon to say whether these changes will work, but TikTok has won cautious praise from child-safety advocates who say its challenges are similar to those facing other platforms, but that the stakes are higher because of its younger audience.

“Three years ago, we were having a really hard time trying to pin them down and get them to do the right thing,” says Julie Inman Grant, Australia’s eSafety commissioner. “They’re starting to be more responsible.”

ByteDance is aiming for more than mere social responsibility. The company’s long-term goal is to eliminate objectionable content entirely, to be “controversy free”, as Tung puts it. It’s a uniquely Chinese censorship strategy – distinct from the hands-off approach of ByteDance’s American counterparts, who tend to express support for almost unrestricted free speech. (Zuckerberg once famously said that Holocaust denial should be permitted on Facebook.) Last year, Zhang issued a public apology after media regulators shut down the app Neihan Duanzi for hosting vulgar content. The company hired thousands of people to police content, giving preference to Communist Party members, and invested more in algorithms to screen posts.

Today, ByteDance’s AI screens videos as they are posted, automatically removing content without waiting for user complaints. The ambition, says Raj Mishra, business head of TikTok India, is to be a “one-stop entertainment platform where people come to have fun rather than creating any political strife”.

He makes no attempt to defer to the freedoms of speech and expression that are written into the constitution of the world’s largest democracy. When asked if TikTok would allow criticism of, for example, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to be prominently featured in the app, Mishra answers, “No”. Last month, Google and Apple app stores blocked new downloads of TikTok in India after a court asked the government to ban the app over concerns about pornography. The ban has since been lifted.

Whether ByteDance ultimately succeeds will depend in large part on its ability to attract older users with more spending power. TikTok has been encouraging cooking, travel and sports videos designed for those crowds. At the same time, it is adding thousands of employees to its 40,000-strong staff and pumping hundreds of millions of dollars more into ad campaigns. It is also working on a search engine, a way for live-streamers to sell products, and a Slack-like chat service for businesses.

According to people familiar with the company, executives have met with bankers to discuss going public. (The company denies it has plans for a public offering.) ByteDance was set to lose about US$1 billion in 2018, according to another person familiar with its financials.

Even so, the company’s global ambitions have been enough to get the attention of Facebook, which released a TikTok-like app, Lasso, in November. While only 70,000 people have downloaded it so far, according to Sensor Tower, Facebook has had success knocking off competitors’ apps in the past. The company released several Snapchat clones before successfully copying its most popular feature, Stories, within Instagram. That caused Snapchat’s growth to slow and Instagram’s to take off.

Zuckerberg seemed to acknowledge the threat posed by ByteDance and other Chinese upstarts last year during a US Senate hearing in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Dan Sullivan, an Alaska Republican, threw him a softball, offering that Zuckerberg’s rise from college dropout to technology mogul might have a patriotic element.

“Only in America,” Sullivan said. “Would you agree with that?”

“Senator, mostly in America,” Zuckerberg replied, noting that “there are some very strong Chinese internet companies.”

“You’re supposed to answer ‘yes’ to this question,” said Sullivan.

Back in Oklahoma, Jade isn’t sweating geopolitics or regulation, and she is mostly off Facebook and Snapchat. On TikTok, she applies a fresh coat of candy apple lipstick and lip-synchs to Kelis’ Milkshake while dancing behind a JCPenney cash register.

“There are nasty people here and there,” she says of her experience using the app. “But for the most part, it’s just a fun, friendly place.”

Additional reporting by Selina Wang, Pavel Alpeyev and Mark Bergen.