Hong Kong is trying to shake its reputation as a haven for dirty money, but has it done enough?

- As the escalating US-China trade war puts Hong Kong in a tight spot, the city has stepped up efforts to put an end to money laundering

- Much has changed since Mr Clean toted cash-stuffed golf bags, but technological advances haven’t ended the practice

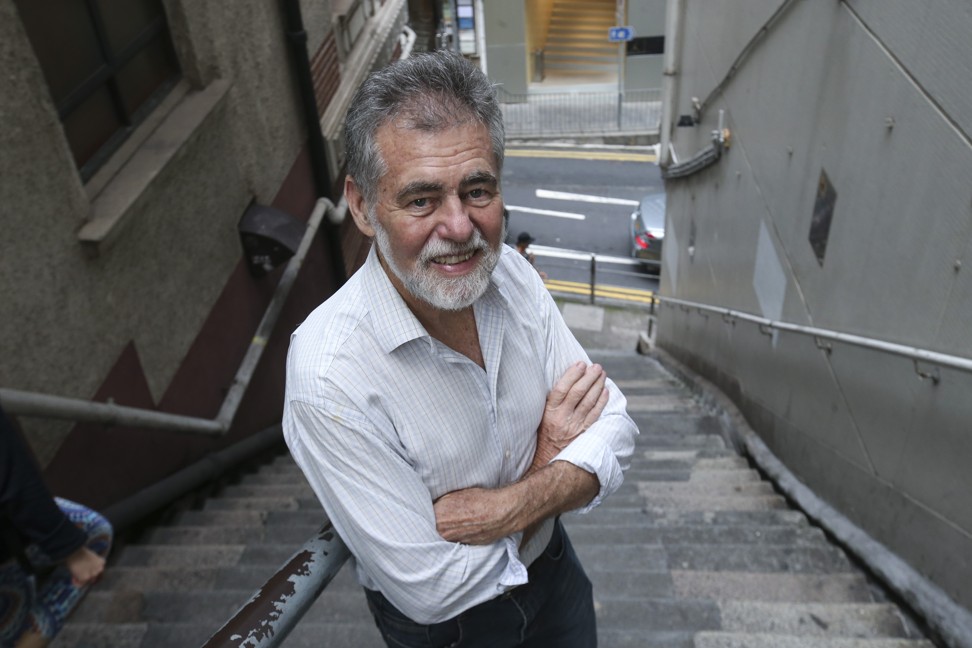

Bruce Aitken, aka Mr Clean, had it easy when he trotted around the globe laundering millions of dollars in the late 1970s and 80s. All he needed was a plane ticket and his golf bag.

Hong Kong-based Aitken, author of the book The Cleaner: The True Story of One of the World’s Most Successful Money Launderers (2017), would fold money end over end, wrap it into squares, stuff it in his bag and get on a plane. Throughout those freewheeling years, when he worked for smuggling operation Deak & Company, he was never once searched at customs.

If bank officials showed an interest in the provenance of the cash, the American would swiftly change the subject to rugby and ask if anyone was up for lunch and a beer. When he arrived back in Hong Kong following trips abroad his banker would roll out the red carpet. “The head cashier was a good friend.”

Fast forward 30 years and Aitken shakes his head when asked how he might go about it today.

“It’s a lot more sophisticated now,” he says. “There is a big industry of compliance. Back in the day, our KYC [know your customer] was to cut a dollar bill in half.” Whoever held the other half, that was who you dealt with.

Each year, an estimated US$2 trillion is laundered around the world, according to the United Nations. There are no credible figures for Hong Kong, but the government admitted last year that its open financial system means there is a “medium-high” risk of money laundering taking place.

What has changed is that more pressure is being exerted by the United States government, which over the past decade has sought to dismantle offshore finance. Hong Kong responded last July by requiring travellers to and from the city to declare cash sums in excess of HK$120,000 (US$15,300).

In the five months to December, more than 12,000 disclosures were made, totalling more than HK$600 billion (US$76.5 billion). The assumption is that illicit money flows are far greater than that figure.

When I started there were no money-laundering laws, but there were foreign-exchange regulations around Asia that prevented people from investing overseas. There was always demand [to get around these laws]. And where there’s demand, there’s a solution

Hong Kong this summer will be rated by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the global money laundering watchdog. Since its last major assessment, in 2009, the government has added a raft of new rules and put an onus on lawyers, bankers and accountants to disclose dodgy dealings.

A good mark from the task force is especially important given the escalation in US-China tensions, and the threat that could pose to the continued recognition by the US of Hong Kong’s special economic status as a customs territory separate from China.

In recent years, the US has “weaponised” its currency by subjecting foreign entities operating outside the country to criminal action when irregular financial dealings have involved the US dollar. This could put Hong Kong in the firing line.

The FATF is to asses what is being done to combat dark flows of money through a country’s financial system by scrutinising its regulation, supervision and enforcement apparatus.

With the 2016 “Panama Papers” showing that Hong Kong is a key middleman in the global offshore business that enables wealthy elites to covertly move cash around, the tightening of anti-money-laundering rules has come as no surprise.

Hong Kong also earns a mention in the 2018 US Treasury report on money laundering: companies here are favourites of transnational criminal organisations.

So just how effective has all this supervision and regulation been in making it more difficult to launder money? Post Magazine set out to see what it would take to clean a fictional million dollars of dirty money.

Across much of the globe, money laundering became illegal only in the 1980s. In Hong Kong, it was in the mid-90s. Long gone are the days of launderers such as Aitken, who moved dirty cash around primarily to circumvent currency controls.

“No one ever checked the golf bag,” he says.

Law enforcers did eventually home in on Aitken and he spent a year in a US jail in the late 80s. Today, he hosts a Sunday radio show for Hong Kong inmates, Hour of Love, and fields questions from journalists and compliance professionals on how he got away with it for so long.

“When I started there were no money-laundering laws, but there were foreign-exchange regulations around Asia that prevented people from investing overseas,” Aitken says. “There was always demand [to get around these laws]. And where there’s demand, there’s a solution.”

Aitken speculates about ways he would do it today, which include using professional money launderers. He hints that he knows where to find such individuals but invokes a strict code of silence when pushed on the subject.

“I don’t want to be a snitch,” he says. “One of the worst things you can be is a snitch.”

The big problem now, says Aitken, even for professional money launderers, is getting cash into the bank.

A plethora of new laws, rules and regulations put banks at risk of fines and sanctions, with the prospect of jail time for their officers,should they facilitate money laundering.

As few as eight years ago, financial-crime teams at banks were relatively modest, according to Ian Morrison, a director at executive search firm Arion House. “These teams have grown astronomically,” he says. Major banks might have once had a handful of people dealing with financial crime in a city such as Hong Kong.

Today, the headcount is likely to be in the hundreds, and for some large institutions, the thousands. While the numbers peaked around 2016 and have since been scaled back, Morrison estimates that there are at least 6,000 financial-crime professionals in the city today. And that does not include compliance staff.

Money launderers set out to take dirty cash and move it through the financial system in ways that disguise its origin in criminal enterprise before parking it in an asset. This is achieved by following a rule of three: first, move the money from your pocket into the financial system (“placement”); then swirl the cash around the system, changing its form to further obscure its provenance (“layering”); and, finally, bring it into the legitimate world of finance (“integration”).

The best approach is to think small, says Julian Russell, an expert in transnational crime who runs corporate intelligence consultancy Pacific Risk. He describes this as “breaking it down until you can’t connect it to the crime. You need to clean it more than once”.

Fortunately, our fictional million is small change in the money laundering world. It could take just 30 minutes to achieve placement in the financial system without setting alarm bells ringing. This is done by what is known as “smurfing”.

Money launderers use friends, associates, minors, the elderly and even unsuspecting tourists to open personal bank accounts and relinquish control.

By using these money mules, or “straw men”, criminals can scatter cash around multiple accounts, depositing small amounts to avoid contravening Hong Kong Monetary Authority guidelines requiring due diligence on transactions of HK$120,000 or more and wire transfers of HK$8,000 (US$1,020) and above.

There are plenty of people who are happy to oblige for a fee, says Russell, and then there are those who have no idea their identities are being used for an illicit purpose. Unsuspecting money mules are often enlisted using spam emails, according to FATF – they might be told they have won a lucky draw and to collect their prize they need to provide a valid government-issued photo identification, such as a driving licence, national ID or passport.

“About a month ago I stood behind a girl at an ATM machine,” Russell says. “The queue was fairly long; it was a Sunday afternoon. She was taking thick chunks of HK$1,000 notes out of her bag, then putting them into the deposit machine, the thickest bundle it would take. She had stacks of ATM cards. She must have been carrying HK$1 million in her bag, at least.”

It took half an hour for her to disperse the money to multiple bank accounts, he says.

Post Magazine put Russell’s anecdote to the test at a branch of a major bank in Central. Within minutes of staking out the bank’s ATMs, two young men arrived with a large backpack from which one pulled out notes while the other held onto a pile of bank cards. For 20 minutes they painstakingly inserted card after card into the machine, each time depositing a few thousand dollars.

Spreading the money widely is the key to avoiding detection. One of Hong Kong’s most infamous cases involved Luo Juncheng, who, at the age of 19, laundered HK$13.1 billion (US$1.67 billion) by way of nearly 5,000 deposits and 3,500 withdrawals into a single account between August 2009 and April 2010.

He was jailed for 10½ years in January 2013. That March, public housing tenant Lam Mei-ling was jailed for 10 years at the riper age of 61, for laundering an average of HK$5 million a day (US$637,000) between May 2002 and December 2005 via 17,000 over-the-counter bank transfers.

Money exchange and remittance is also an effective placement method if the sums are small and multiple operators are used. No questions were asked and no proof of identity was sought when we inquired at various Kowloon remittance outlets about moving cash to an individual or account in Cambodia, Ethiopia, Pakistan or Serbia – all deemed “high risk” jurisdictions by FATF.

Typically, money mules are also used in this process, sending cash offshore before transferring it back after a period of time. In theory, identity checks and an address or telephone number are required for transactions of HK$8,000 and up.

Then there are informal money movers, such as the honour-based hawala system, through which cash is exchanged for a note promising an equivalent sum will be delivered to someone else, somewhere else.

There was no shortage of offers to move a substantial amount of money across borders at one building in Tsim Sha Tsui, and no identity checks were required – but some might find the prospect of receiving a piece of paper in return for their cash daunting.

Another way of distancing cash from a crime is to use cryptocurrencies. When trading mainstream cryptos such as bitcoin, transactions are pseudo-anonymous: a digital wallet must be created and an individual’s identity can be traced via an internet service provider unless it is blocked or a wallet is specifically set up to protect the identity.

A professional money launderer would instead likely use a more anonymous altcoin – an alternative to bitcoin – and make use of a tumbler, which exchanges any identifiable cryptocurrency with that of other people to obscure the original source of the funds.

Tumblers, though, are being targeted by regulators. On May 22, one of the largest crypto tumblers, Bestmixer.io, was shut down by authorities in the Netherlands and Luxembourg, working with Europol. Bestmixer had a reported turnover of US$200 million in the year since it had launched.

Other crypto mixers can still be found online, as can peer-to-peer exchanges where hard cash can be used to purchase cryptocurrency.

Hopes of walking up to a bitcoin trading desk in Tsim Sha Tsui with a suitcase full of fictional money were thwarted by the abrupt closure of said desk, following the cryptocurrency’s spectacular nosedive at the start of last year. (Bitcoin has since rebounded but there is no word of the exchange reopening.)

Inquiries were then made with a seller of cryptocurrency on a peer-to-peer exchange: the rate was not favourable but he was willing to be paid in stored-value cards – which can be purchased at convenience stores and the code on the card passed along. Other peer-to-peer exchanges can then be used to buy and sell more of the altcoin and keep the illicit cash moving before being placed in an account of choice.

All of these methods are complicated. More straightforward, particularly where large sums are involved, is to get a trade – or to make it appear that you have one.

Setting up a business takes very little effort and allows dirty cash to be mingled with legitimate money at relatively low cost. You could even set up a company that has no physical presence and no actual business. The trick is to persuade a bank to accept your money.

Establishing a company in Hong Kong is relatively easy, but at least one natural person (as opposed to a business entity) is required. Criminals will often use a proxy so the company cannot be traced back to them. This has become more difficult since the amendment of company law last year to force firms to keep a register of who is in control.

The average criminal, however, is probably not above lying about this, or using fake directors in the first instance: company registration, notes Russell, has a number of weak spots. Proof of identity and an address are required to set up a company but original copies are not necessary and faxed copies of passports can be easily doctored.

“If it’s a passport from Lithuania, for example, there’s no way of verifying that,” says Russell.

Calling around some of Hong Kong’s 6,488 licensed trust or company service providers (TCSPs), which will set up a company on behalf of an individual, suggested verification of identity documents was not a priority. “There won’t be any verification directly with any authority or other body,” one TCSP assured us.

A spokesperson for the Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau (FSTB) insists that the Companies Registry conducts “vigorous” site inspections of companies to ensure compliance with legal requirements, including the register of significant interests outlining those who control the company.

Hong Kong, though, has nearly 1.4 million incorporated companies. None of the TCSPs was willing to trade money for morals by acting as a nominee director, however. “It’s not workable any more,” said one. Another suggested getting “a trusted friend” to take on the role instead.

Where the TCSPs can be of help is in opening a corporate bank account. Several boasted excellent relationships with banks. One TCSP guaranteed an interview with six banks. Another recommended opting for a small, local bank. “They will want identification,” we were told, “but they won’t verify it.”

Laundering a million dollars might be harder than it was in Mr Clean’s heyday, but it is far from impossible

Other TCSPs suggested setting up an overseas bank account – which can be done online – or an account with a bank “alternative”, for which a copy of an identity card or passport is all that is needed. Although not technically a bank, these offer many of the same services. They provide prepaid credit cards and the ability to send and receive money globally, as well as allowing ATM withdrawals from Hong Kong banks.

Once a company is up and running, it can get creative with invoices in order to mingle good money with bad – most businesses set up for money laundering create fake transactions or inflate bona fide ones. Cash-based businesses are best for this, anything from a market stall to a nightclub.

“Scrap metal is good,” says Russell, “because there are no serial numbers on it.” And while the company’s auditor is required by law to report suspicions of money laundering, in 2018, of nearly 74,000 suspicious transaction reports made to authorities in Hong Kong, just 0.03 per cent were filed by accountants.

Trade-based money laundering is effective too for layering, further obfuscating money from its original source, and for the integration of illicit money, for example, by using the company to buy big-ticket items, such as property.

Hong Kong requires real estate agents to verify the identity of the ultimate owner of a property but, as with accountants, suspicious transaction reports are not prevalent.

Of all such reports last year, just 0.06 per cent were from real estate agents. And a sophisticated money launderer would be unlikely to pay for a property with a suitcase full of cash: by this stage their dirty money will have been washed several times and appear legitimate.

So laundering a million dollars might be harder than it was in Mr Clean’s heyday, but it is far from impossible. And while Hong Kong has adopted reams of new regulations and its institutions have loaded up on compliance lawyers and box checkers, the number of prosecutions for money laundering remains small and is falling.

To date this year, 21 prosecutions have been brought, compared with 86 in 2018 and 138 in 2013. In 2013, some HK$873 million (US$111 million) of assets were seized by law enforcement, versus HK$7.8 million (US$1 million) last year. Whether that is a sign that regulation has been successful in deterring criminals is difficult to determine.

As hawks in the US administration prepare for the possibility of a full-spectrum stand-off with China, Hong Kong, as the principal centre for US-dollar trading in Asia-Pacific, finds itself nervous and exposed.