Chinese artist and author Chiang Yee takes rightful place in British cultural history

- The Jiangxi-born author of the Silent Traveller series of books showed wartime Britons a unique view of China

- He is honoured by a blue plaque on the facade of the Oxford house in which he lodged, lived and worked for 15 years

In the summer of 1940, Chiang Yee knocked on the door of 28 Southmoor Road, Oxford. It was opened by Henry and Violet Keene, who offered the traveller a bedroom on the upper floor of the unassuming terraced house, and the front room facing the quiet residential street as a study.

Chiang had arrived in the British university city after being bombed out of his lodgings in north London during the blitz of World War II. Moving from door to door and asking for a room for the night, what he thought would be temporary lodging became his home for the next 15 years, during which time he honed his extraordinary artistic ability and prose, writing about the British and painting scenes of their country.

Chiang’s observations secured him a place in the hearts and minds of Britons who looked to him for insights into the mysterious Middle Kingdom, while he in turn looked to them for traits he believed to exist in all of us, regardless of race or nationality.

“I am an Oriental,” Chiang wrote in the introduction to his third book, The Silent Traveller in London (1938), part of a series that would earn him legions of Western fans, “I am bound to look at many things from a different angle. But is it really so different? I very much doubt it myself […] I have never agreed with people who hold that the various nationalities differ greatly from each other. They may be different superficially, but they eat, drink, sleep, dress, and shelter themselves from wind and rain in the same way. In particular their outlook on life need not vary fundamentally.”

It was his belief in the universality of nature and his quest to find close contrasts between his homeland and abroad that spawned some of his finest work – a prodigious body of art that spanned into ballet and children’s books, and all showcasing Chinese culture directly to Western audiences.

And now, more than 40 years after his death, with a new generation facing new tensions between East and West, a band of academics, writers and readers, have given Chiang the recognition they believe he deserves. It is an honour usually reserved for the likes of legends, and the locations in which they lived in Britain: Arthur Conan Doyle in Westminster, John F. Kennedy in Kensington, Karl Marx in Camden. And Winston Churchill, of course.

This year, Chiang has been honoured with his own blue plaque, forever linking him to his place of work and his place in British history – affixed to the wall of 28 Southmoor Road, Oxford.

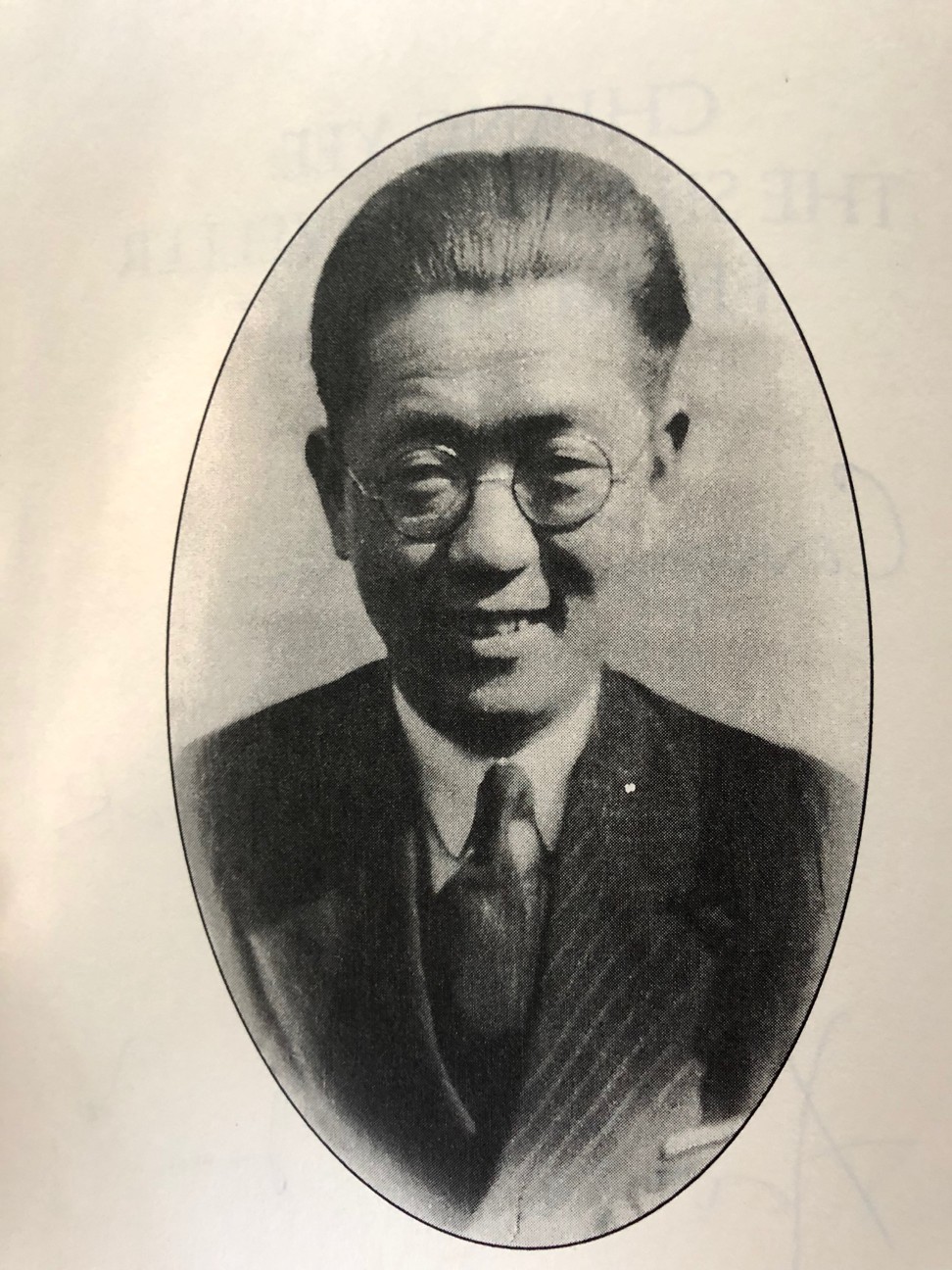

Chiang was born into a wealthy family on May 19, 1903, in Jiujiang, Jiangxi province, on the banks of the Yangtze River at the foot of Lu Mountain.

His father, Chiang Ho-an, was a Confucian scholar and portrait artist and indulged Chiang’s early interest in painting and calligraphy, practices that would blossom on the other side of the world.

Chiang studied chemistry at the National Southeast University, in Nanjing, believing science would bring about prosperity to China, a country still attempting to find its way following the 1911 overthrow of imperial rule.

In 1924, he married his cousin, Zeng Yun, to whom he had been betrothed since birth, and their first of four children, Chien-kuo, was born two years later. Chiang’s artistic side might have remained dormant for the rest of his life, as family demands saw him take up a teaching post at Shanghai’s Jinan University.

He took leave in 1927 to join the Nationalist Kuomintang government’s Northern Expedition, to quell the warlords running amok, and earned his stripes as a respected leader, taking up a variety of roles in local government in and around Jiangxi, including as a circuit magistrate.

But he became disillusioned with the corrupt Kuomintang administration and the broken political system. The restless artist within was stirring. Asking his brother to keep an eye on his family, Chiang boarded a ship in May 1933 for Britain, to take a master’s degree in civil administration at the London School of Economics, on the completion of which he planned to return to help China modernise and prosper. He arrived in Britain with few possessions and speaking only a few English phrases.

Via the Chinese diaspora he found a flat-share in London’s Hampstead with compatriot and playwright Hsiung Shih-I, the first Chinese person to direct a West End play, the highly successful Lady Precious Stream, an adaptation of the classical Peking opera Wang Baochuan.

I did not set out to turn the British scene into a Chinese one […] rather to interpret British scenes with my Chinese brushes, ink and colours, and my native method of painting

Noticing Chiang’s painting talent, Hsiung invited him to illustrate a publication of the play, which was well received by critics and Chiang’s name began to circulate in London’s creative community.

Chiang’s neighbours in Hampstead were made up of artists and intellectuals, including oriental-ceramics expert William Wilberforce Winkworth, poet and art scholar Laurence Binyon, art critic Herbert Read, painter Roger Fry, and George Eumorfopoulos, a collector of Chinese art.

Captivated by the energy of pre-war London and his bohemian neighbourhood and peers, Chiang began to write in English, calling upon his new friends to help out as editors. And he began to evolve his artwork, painting British landscapes and street scenes.

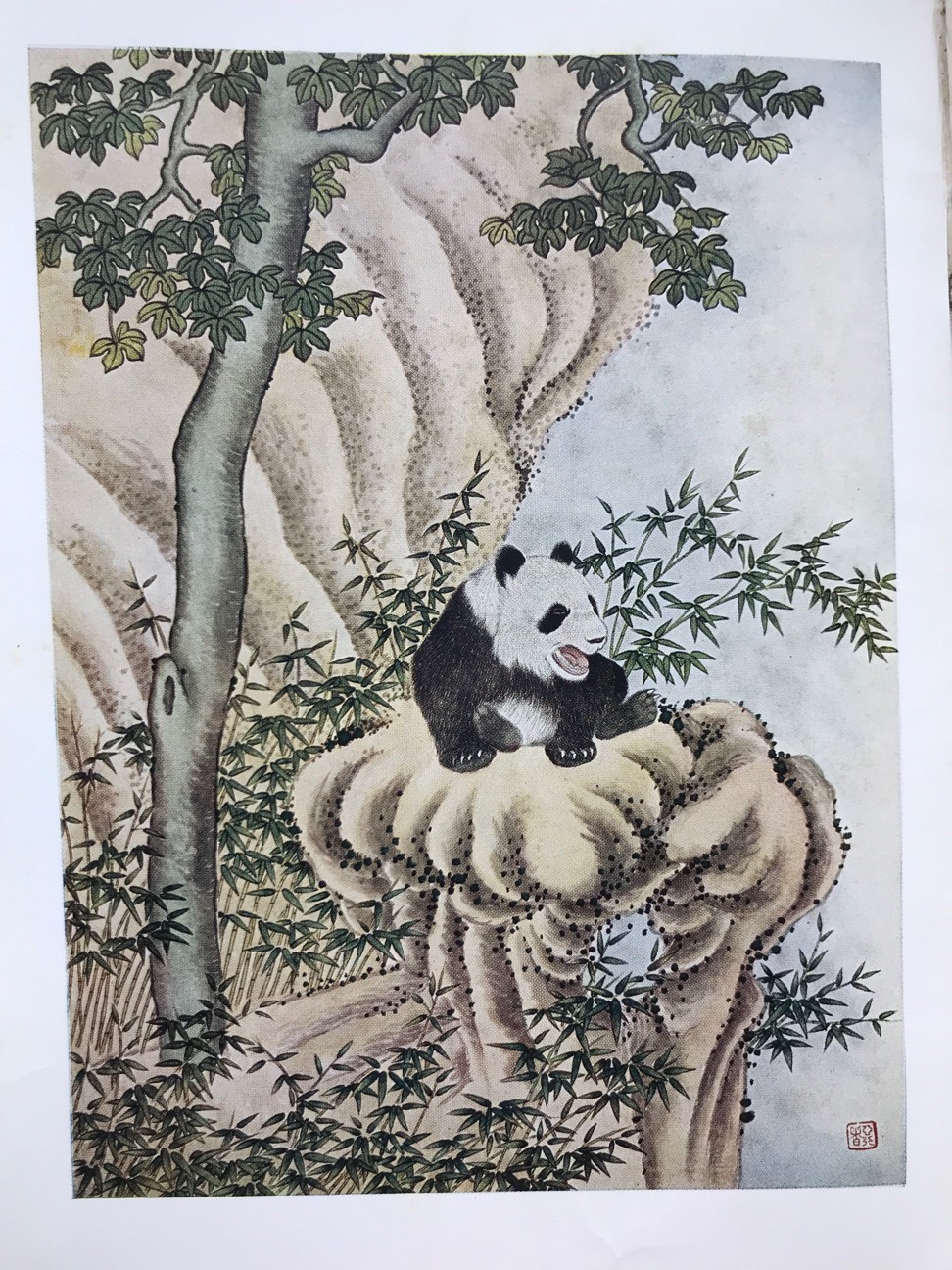

His illustrations were executed in the traditional guóhuà (native) style, using Chinese materials – ink, brushes and absorbent paper. Chiang applied many of the principles of Chinese painting, though as he later wrote: “I did not set out to turn the British scene into a Chinese one […] rather to interpret British scenes with my Chinese brushes, ink and colours, and my native method of painting.”

A small exhibition of Chinese art in an offbeat gallery led to one of his illustrations being printed in the London Evening Standard newspaper, bringing his work to wider public attention.

Not quite getting by only selling his paintings, Chiang took a post teaching Chinese at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Then came his big break. In 1935, the Royal Academy of Arts began planning a large-scale international exhibition of Chinese art. A book was to be published to accompany the showcase and Chiang was commissioned to write it. The Chinese Eye – his first book – was published that November, a month before the exhibition’s opening.

In the introduction, Chiang wrote: “The painter’s aim is to convey an atmosphere, a poetic truth […] Whether we paint a small orchid, a young [bird] tit or the rugged cliffs of the Yangtze gorges, we must always have some poetic message to convey. If only we can transfer to the mind of the onlooker this fruit of our dreaming contemplation, we have no care for verisimilitude.”

The book sold out quickly and had to be printed twice within two months, its instant success launching Chiang on his writing career.

“Thanks to Chiang, Chinese art appeared easily accessible to both experts and laypeople. With remarkably lucid language, engaging anecdotes and humorous comments, he explained the Chinese conception of art to the British, and he discussed in great detail the relationship between Chinese painting and philosophy, history, literature and nature,” says his biographer, Professor Da Zheng, an academic at Suffolk University, in Boston, the United States.

With one eye on the streets of London, Chiang was also watchful of events taking place in his homeland. The 1936 Japanese invasion troubled him and his mounting anxiety caused his friends to advise him to take a break from the bustle of London and head to the countryside.

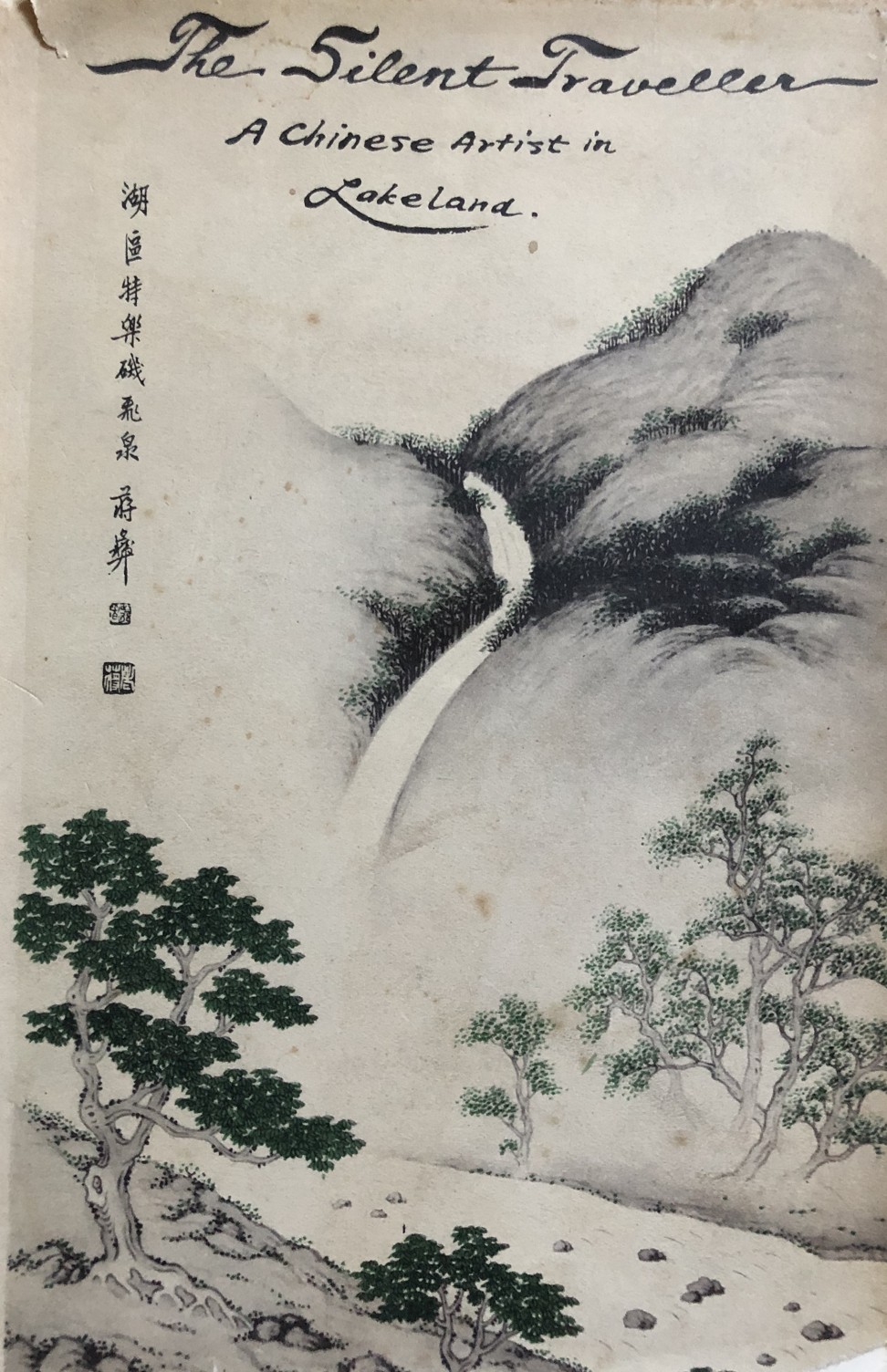

He travelled north, to the Lake District, a place of dramatic peaks, meandering tarns and misty fells – vistas and hikes that had inspired the imagination of the English Romantic poets, chief among them the poet laureate William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey and J.M.W. Turner.

Chiang found in the beauty of the Lake District his fundamental belief in nature’s potency and influence over the human spirit, and he made a journal of his walks and painted the landscape.

Buoyed in spirit, on his return to London he contacted publishers, pitching the idea of a book called The Silent Traveller, illustrated with his paintings. He enlisted the editing talent of his friend and student of Chinese, Innes Jackson.

He received only rejections. Then, in 1937, Country Life magazine, which had initially rejected his proposal, agreed to publish his Lake District writings, though on the condition he accepted only six complimentary copies of the 67-page tome as royalties.

The Silent Traveller: a Chinese Artist in Lakeland was published in late 1937 and included 13 of his illustrations, which for the viewer transformed familiar English scenes into Chinese idioms. Many of the illustrations were accompanied by verse written in elegant Chinese script with English translations – a visual and literary combination used in the traditional Chinese practice of inscribing poems on paintings. Chiang’s prose also has clear poetic qualities.

Describing the morning of a boat trip in the Lake District, Chiang wrote: “Next I came to the boats’ landing stage; looking across to the other side as far as I could see, the mountain ranges stood out clearly against the blue sky and even the beams of sunlight could be separately counted. The morning smoke was steadily puffing up from the chimney of some house hidden in the mass of trees and only a roof might be hazily discerned through the mist.”

Like his first book, this, too, sold out in a month and it, too, required several reprints. Its success led to more Silent Traveller books, on London, the Yorkshire Dales, Oxford and Edinburgh, and Wartime; all edited by Jackson, and some translated into Chinese.

The illustrated travelogues were, as Chiang wrote, written from “the point of view of a homesick Easterner”, and the series became his most significant commercial and artistic success, finding a wide readership throughout the English-speaking world.

Books on China were common, even popular among Westerners, but an intimate exploration of Britain with detailed descriptions of British culture, society and landscape, delivered with poetic prose and perceptive illustrations by a Chinese writer, was a rarity.

“Many travellers who have gone to China for just a few months come back and write books about it, including everything from literature and philosophy to domestic and social life, and economic conditions,” wrote Chiang. “And some having written without having been there at all. I can only admire their temerity and their skill in generalising on great questions. I expect I suffer together with many others in the world, whose characters have been mis-generalised in some way.”

Tessa Thorniley, a PhD student researching Chinese authors at the University of Westminster, says echoes of Chiang can be found in the bestselling books by US travel writer Bill Bryson, who wrote about Britain and the British in his first hit, Notes from a Small Island (1995).

“Both were super popular,” says Thorniley, “good at interpreting different cultures, used humour in their work and used a travel format […] Chiang’s style was always amused rather than cynical or satirical, which drew British readers in.”

Chiang’s third book, The Silent Traveller in Wartime, published in 1939, was dedicated to his brother, who was killed in the first months of the Sino-Japanese war and poignantly written in the form of a letter to him. Despite his mourning, Chiang’s narrative is upbeat and frequently describes scenes of beauty in his war-torn surroundings, such as “silent shoals of barrage balloons drifting in the moonlit sky”.

In the preface he explains why he focused on small details of seemingly insignificant things: “The pain I had suffered from the war is beyond description. My motherland was conquered by enemies; my hometown fell; my house demolished; and my family scattered apart, thousands of miles away from me. Tormented by painful homesickness, how could it be possible of me to have a leisurely and carefree mood to compose something insignificant like this? But I did it and it was really because of something too painful to disclose.”

The ‘Silent Traveller’ was a mask he wore that enabled him to observe things around him with humour [...] to survive, to discuss small things and to observe little details

“He lost much during the war, which was very hard for a writer in exile,” says Thorniley. “The ‘Silent Traveller’ was a mask he wore that enabled him to observe things around him with humour even when war was raging. The mask enabled him to survive, to discuss small things and to observe little details. His writing suggests a great familiarity with his surroundings but he also suffered from feelings of alienation.”

Indeed, Chiang suffered depression and anxiety throughout much of his life – poor mental health brought on by the guilt of leaving his family.

An entire chapter of The Silent Traveller in London is devoted to his observations about children. He liked to “study their actions and manners – the results of training, upbringing and national discipline”, he wrote.

“He missed his own, who were growing up and changing without him,” adds Thorniley. “So there is always some sadness in the way he writes about children. He had a great love of children and made time to play with, write to, and draw the children of his close friends.”

Life’s minutiae, mundane matters such as queuing for buses, drinking tea and families out together, fixated him. Each chapter is called by a simple noun: “On Food”, “On Men”, “On Women”, “On Drink and Wine”, “On Children”, “On Old Age”, “About Tea Time”, and in each he compares Chinese traditions with British. The first half of the book is devoted to the seasons – “Spring in London”, “Summer in London”, and so on – the same natural yearly cycle that inspired Chinese and British poets to create verse.

He adored London’s parks, which he painted and wrote about often. “I like to wander in London parks when it is windy, because I can see the quivering shapes of the tree branches and the leaves being blown all in one direction or in confusion, producing a special sound very agreeable to listen to.”

Steering clear of politics and the more unpleasant realities of pre-war British life, the critic can easily sense superficiality in his musings. Yet Chiang was capable of adopting a critical tone and poking fun at his subjects.

Remarking on a fad among British women for wearing historic Chinese garments, he wrote: “I was once struck by a lady who wore an old Chinese robe at a party. She was very proud of her gown […] but I am inclined to wonder what English people would think of a small and short Chinese lady wearing an Elizabethan type costume picked up from the drawer of a repertory theatre. I can almost imagine the head of the lady would not even emerge from the huge skirt.”

He then drew a cartoon of his imagining and included it in The Silent Traveller in London.

Chiang was happy to quote Lord Bryon in one paragraph and Confucius the next, drawing on the literati of both China and Britain to make his point of human commonality. A clearly defined purpose of his work was to offer readers an alternative to the stereotypical image of Chinese portrayed in films and books – the racist tropes of Chinese as coolies, opium-smokers and villains.

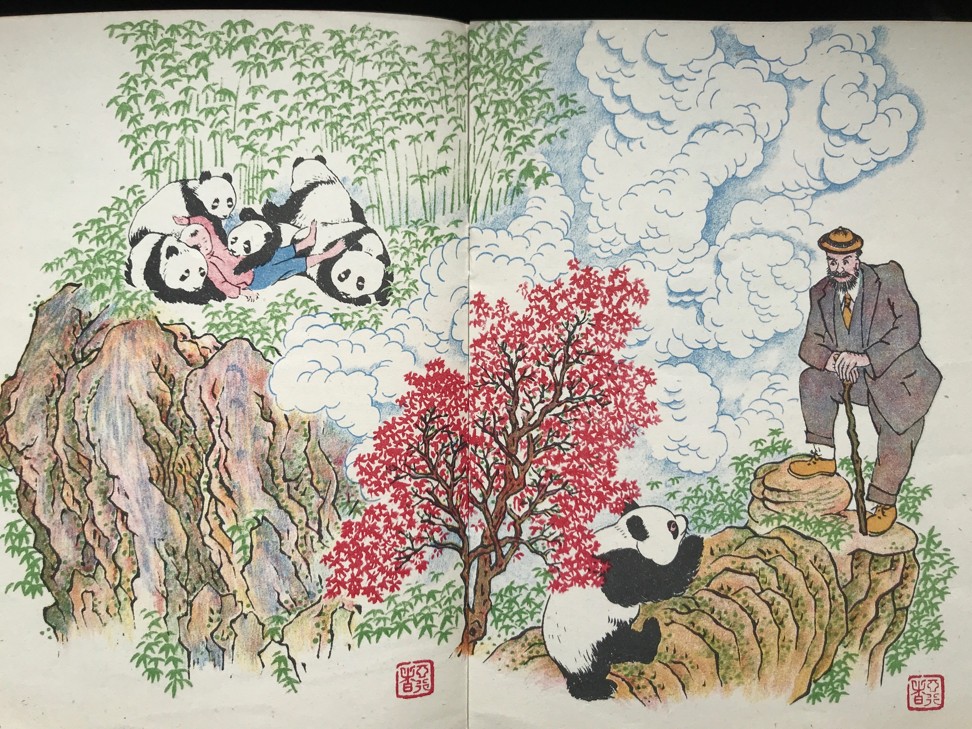

He could be subversive, too, as made evident in his bestselling children’s book featuring pandas. Chin-pao and the Giant Pandas (1939) is believed to be the first time the iconic Chinese bear had been depicted in cartoon style.

In the chapter “A Young Confucius”, the pandas take Confucius to task. The boy protagonist, Chin-pao, talks to the pandas about how to lead good lives, and then father panda says: “I wish you would mention Confucius less often. We have heard too much about him, the silly old man!”

Father panda later says: “Chin-pao, you are still too young to understand all this. Some of our ancestors lived before Confucius was even born. We know how to live. We have knowledge of everything, but we do not bother. We are very kind to each other without any fuss and we have never killed even the smallest insect.”

In September 1940, Nazi bombs began to fall on London, where during one raid Chiang’s Hampstead apartment was obliterated. He and his flatmates, including Hsiung, escaped unharmed though much of their original work – notes, sketches and paintings – were lost.

Chiang decided to evacuate the capital and head for Oxford, from where he would travel the country, commuting regularly to London to lecture and commentate on Chinese art, poetry and literature. He was regularly heard on BBC art programmes, linking listeners to China and telling them of his transcultural and transnational experiences.

In 1999, Professor Zheng, then a PhD student, trod in the footsteps of his biographical subject and knocked on the door of 28 Southmoor Road. It was opened by Pauline and Richard Jones, who have lived there since 1977.

Zheng told the Joneses how he was researching the life of an extraordinary Chinese man who once lodged in the home, and the young academic from America was invited in to inspect the house, which had undergone alterations, but with Chiang’s front-room study and bedroom still in situ.

Zheng discussed with the Joneses how Chiang had lived in their house while creating his Silent Traveller series, and that after World War II, visited the US for the first time, and his six-month trip resulted in another book, The Silent Traveller in New York (1950).

I heard about the scarcity of blue plaques for ethnic minority people. He made an important and creative impact on British society and his work should be remembered

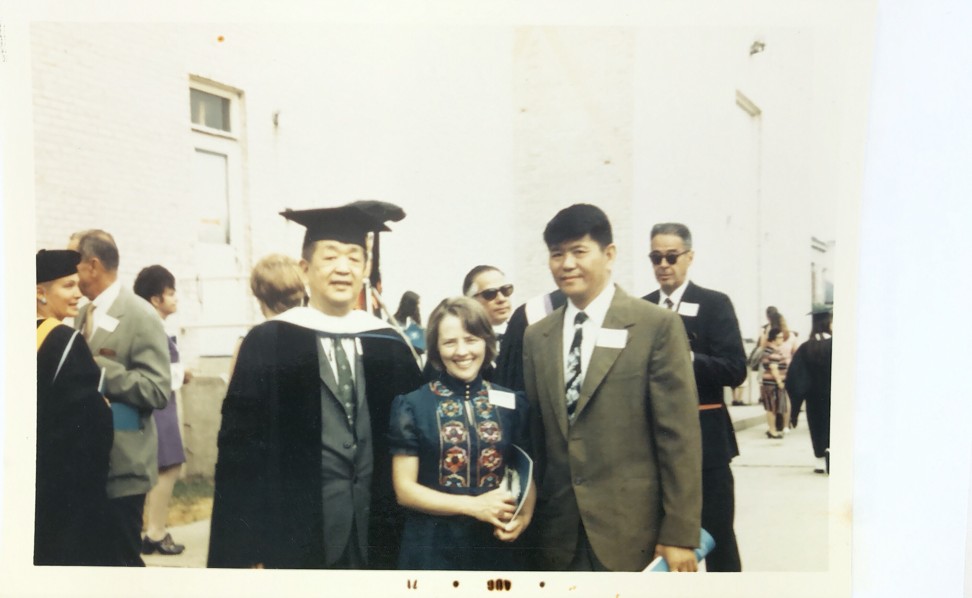

In 1955, Chiang moved to the US to teach Chinese studies at Columbia University, where he went on to become emeritus professor of Chinese, and during the next two decades published four more travel books, on Boston, Paris, San Francisco and Japan. In a speech given at Harvard University, titled “Chinese Painter”, Chiang called for the interdependence of all cultures in the modern world, winning him a new band of admirers.

The Joneses at 28 Southmoor Road and Zheng kept in contact over the next 18 years. A little over a year ago, he called to say that efforts were afoot to have a blue plaque placed on the facade of their house if they were in agreement. They were.

Among Chiang’s many fans are author and China specialist Paul French and his partner, Dr Anne Witchard, a reader in English studies at the University of Westminster. They responded to a campaign launched by English Heritage in 2016, calling for a more representative celebration of British history after a survey showed that of the 900 blue plaques, just 14 per cent celebrate women and just 4 per cent are dedicated to black and Asian figures.

French, the author of the bestselling Midnight in Peking (2011), was given a copy of The Silent Traveller in London by his father as a teenager. “He knew I was interested in studying Chinese and picked the book up in a second-hand bookshop,” says French. “It was an eye-opener for me and remains one of my favourite books […] I thought Chiang was an excellent candidate when I heard about the scarcity of blue plaques for ethnic minority people. He made an important and creative impact on British society and his work should be remembered, so we sent in an application.”

An international symposium on Chiang was held in Oxford University’s Ashmolean Museum ahead of the plaque’s unveiling this June – the velvet ceremonial cloth tugged from the wall in front of a large crowd by Rita Keene Lester, whose parents, Henry and Violet, had welcomed Chiang into their home 79 years ago.

“I remember him as an uncle figure,” she tellsPost Magazine. “He was very generous, and taught me some calligraphy and Chinese phrases. He would take me to the park and, in later years, buy me and my friend lunch.

“He was quiet – he kept to himself much of the time but he would eat with us, and help prepare food, especially the fish my dad caught in the local rivers. He would prepare them in a very different way. And he would scold us in English for the way we overcooked our vegetables.”

Chiang’s granddaughter, Sudi Chiang, who lives on the British Channel Island of Jersey, was also present at the blue plaque unveiling. “I am very proud of my grandfather’s achievements and I am certain he would be very honoured to know he has a blue plaque in his name, as well as being humbly surprised,” she says. “I am sure he never imagined when he knocked on the door of 28 Southmoor Road in 1940 that all these years later a blue plaque would bear his name outside.”

We live a very fast-paced lifestyle in a constantly changing world. Chiang Yee showed us that we need to slow down, to be more observant and mindful, and appreciate life, nature and the people around us

The Sino-US relationship was restored in 1972, and in 1975, Chiang finally returned to China, where he wrote China Revisited: after Forty-two Years. It was published posthumously in 1977.

“The [last] book was unusually passionate, emotional and straightforward in presentation – markedly different from the calm stance and neutral tone found in the Silent Traveller series,” says Zheng.

Chiang died on a day variously recorded as October 7 or 26, 1977, aged 74. His ashes were placed in a tomb on the slopes of Mount Lu above his hometown – the great traveller made a permanent part of the landscape that influenced him.

“We live a very fast-paced lifestyle in a constantly changing world,” says Zheng. “Chiang Yee showed us that we need to slow down, to be more observant and mindful, and appreciate life, nature and the people around us.”