Cambodia’s digital surveillance serves to silence the opposition and suppress criticism of the government

Private phone calls and social media posts are being used against individuals

For citizens, such intrusion provides a sinister reminder of the dark days of Pol Pot’s murderous regime

Last month, two members of Cambodia’s forcibly dissolved opposition party – the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) – were arrested and charged with incitement, defamation and violating a Supreme Court order.

When Sun Bunthon and Nou Phoeun were brought in by police, they were surprised to hear officers read out a transcript of a private phone call, in which the arrestees had encouraged the return of the party’s exiled co-founder, Sam Rainsy, who has been charged with treason and a host of other politically motivated crimes.

The pair’s lawyer, Sam Sokong, declined to speak about the case over the phone, preferring to meet in person. “The CNRP activists feel afraid to converse on their phones,” said Sokong. “I cannot talk about any serious thing on the phone.”

Sokong said he was in the room with his clients when the police read the transcript, and that the police had no warrant giving them permission to record the conversation but they did so anyway because it was a matter of “national security”.

While these were the first arrests definitively linked to phone tapping in more than a year, Cambodia has a long history of pressing criminal charges over private phone conversations. Even before technological advancements allowed the Cambodian government to access its citizens’ phones, surveillance was a part of life.

Coffee vendor Samnang was a young boy when the totalitarian Khmer Rouge took control of Cambodia in the mid-1970s, but he still remembers the sinister slogans about Pol Pot’s nascent Communist Party having “the many eyes of a pineapple”.

Under its infamously cruel dictator, the communist regime used manipulative rhetoric along with brute force to intimidate and control ordinary Cambodians, and in less than four years, an estimated two million people had been killed. The families of those accused of being traitors were often killed along with the offender, including infants. “When pulling out the weeds, remove the roots and all,” went a popular aphorism at the time.

At the centre of it all was the idea of “Angkar”, an omniscient entity that embodied the ruling party: the Khmer Rouge convinced ordinary Cambodians that any transgression, even stealing a grain of rice, would be discovered and punished. “Everyone would report another’s mistakes and Angkar knew everything,” says Samnang.

While primarily Buddhist, Cambodian animist beliefs are teeming with spirits and ghosts, and many survivors describe Angkar as a supernatural entity. Academic researcher Peg LeVine, who testified as an expert witness at the trial of the Khmer Rouge leaders, says, “Many victims perceive Angkar as an ‘it’ with timeless omnipresence.”

A trauma psychologist and anthropologist, LeVine conducted a decade of filmed research into the effects of the Khmer Rouge and what she coined as “ritualcide”.

LeVine concluded that the Khmer Rouge did not purposefully create Angkar, but rather the belief that there was “an invisible possessing force that can read and infiltrate people’s minds” arose organically through ritualistic and ancestral influences.

As a nation that is still collectively suffering from the extreme trauma experienced under the Khmer Rouge, it is easy to take advantage of these latent fears to achieve new goals.

Enter “Seiha”, a modern upgrade to Angkar, technology that listens to phone conversations, intercepts text messages, and feeds it all back to Prime Minister Hun Sen. Originally a little-known Facebook page, Seiha rose to notoriety in 2016, when the site began hosting recordings of secretly leaked phone calls, and played a crucial role in attacks on the CNRP, exposing internal conflicts, sex scandals and allegedly “defamatory” criticisms of the government. Seiha’s message reached wider audiences when it became a mainstay of a highly ranked news site and government propaganda machine, Fresh News. Videos posted on Seiha’s page were immediately redistributed by Fresh News, reaching an audience of millions.

“To the extremist group, please be careful. Seiha listens every day,” Hun Sen once warned the CNRP. LeVine says it would be “creepy” and “cruel” if the Cambodian government is purposefully invoking memories of Angkar through surveillance, and yet, Fresh News and Seiha have created a climate of paranoia, in which ordinary people fear their phones could be tapped.

“As survivors have told me how Angkar enters their night terrors today,” says LeVine, “one can only imagine the shadow cast by Seiha.”

Before CNRP leader Kem Sokha was charged with treason, Seiha circulated conversations between him and an alleged lover, culminating in a prostitution charge. Kem Sokha evaded arrest by holing up in CNRP headquarters for months until a royal pardon eased political tensions.

At the time, Anti-Corruption Unit director Om Yentieng admitted, “We can tap whatever we want.”

Another politician, Lu Lay Sreng, fled the country after Seiha leaked a recorded phone call of him insulting the king and accusing the ruling party of corruption.

While only the government has the authority to monitor phone conversations, no investigation has ever been conducted into Seiha’s identity, suggesting official affiliation. Hun Sen’s own son serves as the head of the military’s intelligence department, while his son-in-law holds a similar position in the national police.

Since 2018, Seiha has been relatively quiet, and that makes sense: the CNRP, the biggest opposition party, is banned, most of its leaders have fled, and party president Kem Sokha remains under house arrest. But the long shadow cast by Seiha continues to be felt. Activists in civil society, labour unions, politicians and even regular Cambodians continue to report that they are being monitored, many making direct reference to Seiha.

We are afraid they would arrest us, they would harass us, they would capture us like Kem Sokha. When we talk about politics we have to be very careful

“Seiha is Hun Sen,”says Kosal confidently, glasses perched delicately on his nose, and wearing a tan button-down shirt with matching trousers at a Phnom Penh cafe. Born to a rural farming family, Kosal came to the capital to study Khmer literature, abandoning his agrarian roots for academia.

An open supporter of the opposition party, Kosal says he used to make Facebook posts critical of the government but, in 2017, his account was hacked and he could not recover it. Kosal signed up for Facebook through his phone number, and believes the government used that to take over his account.

“I very rarely use the normal call function because they listen to everything,” he says, explaining that he uses the Signal messaging app to discuss politics. He says other CNRP supporters he knows are also fearful. “We are afraid they would arrest us, they would harass us, they would capture us like Kem Sokha,” he says. “When we talk about politics we have to be very careful.”

At the same time, Cambodian access to social media continues to skyrocket, with Facebook users rising from 6.8 million to 8.8 million in the past year. But the platform remains fraught, its users regularly arrested for posts critical of the government. Talking to the press is also risky – a tuk-tuk driver was summoned for questioning in August after speaking to the South China Morning Post.

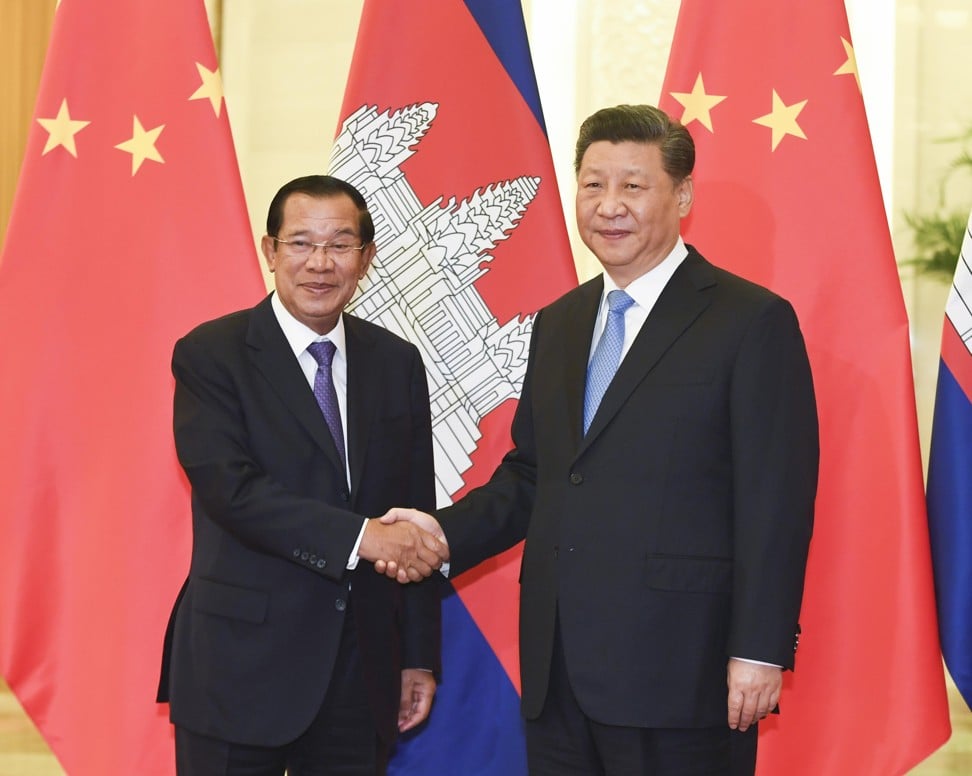

Human rights organisations routinely criticise the government for widespread abuses and Cambodia consistently ranks among the worst countries for corruption and judicial independence. Despite this, Hun Sen’s grip on the country remains ironclad, propped up by financial and economic support from his closest ally, China.

To maintain power, Hun Sen banks on the country’s steady economic growth and its history of horrific violence, often invoking the memory of the Khmer Rouge as a warning against any attempt at a revolution.

With 65 per cent of the population aged under 30, most Cambodians did not live through the Khmer Rouge, but the communist regime remains ever present. Hun Sen bolsters his political legitimacy by describing himself as Cambodia’s saviour from the Khmer Rouge while warning that chaos will return if he leaves office.

When an unnamed brain surgeon allegedly badmouthed the prime minister’s eldest daughter, Hun Sen warned: “I know your face, name, residence and that you are a brain surgeon; you should not be a fool like this.” He later added, “Seiha heard that and shared to me.”

Bunthorn was a child during Khmer Rouge rule. He says Angkar served the same purpose that Seiha does today. “For example, during the Khmer Rouge, if you talked upstairs, the Angkar will stay under your house so it’s the same as Seiha is doing now,” he explains.

But Seiha is not the same as Angkar. It’s not as all encompassing, nor as mystical. As Alexander Laban Hinton, professor of anthropology at Rutgers University, Newark, in the United States, wrote in Why Did They Kill? Cambodia in the Shadow of Genocide (2004), “Angkar supplanted Buddhism as the new ‘religion’.” Hinton calls Angkar “totalistic, pervasive, and all-knowing”.

Seiha is more mundane, an Angkar for the post-Edward Snowden era when surveillance brings to mind less an all-seeing spirit and more intelligence agencies such the US National Security Agency. In 2017, when a conversation between Hun Sen and Kem Sokha was leaked, the prime minister joked, “I am surprised the Facebook page, known as Seiha, is able to hack my conversation with Kem Sokha. Such equipment can only be used by the US, Israel or Germany.”

Paul Craig, head of offensive security for Singaporean cybersecurity firm Vantage Point, says it is likely the government has direct access via telecoms companies.

“I have worked with many telcos over Southeast Asia and all of them have [lawful intercept, LI] capabilities. It’s usually a legal requirement for a telco/ISP to provide LI to law enforcement in most countries,” he says by email. “Typically LI access is governed by a legal framework and requires a warrant and strict legal protocols about what and who can be monitored. However, without a clear and strong legal framework protecting access this could be very easily abused.”

Cambodia’s Law on Telecommunications has been criticised for being too vague. It allows phone tapping if approved by an undefined “legitimate authority” and requires that all telecom companies provide information and data to the government if requested.

Craig added that Cambodia’s deepening relationship with China should be a cause for concern. “China is becoming the surveillance master of the world, and if Cambodia were setting up a China-esque surveillance programme you may have reason to be worried.”

Text: Coda