How songs became powerful weapons for protesters around the world

From Glory to Hong Kong to Blowin’ in the Wind, songs taken up by civil movements have brought people together through a shared sense of purpose

On a crisp winter evening at Tai Po Waterfront Park, musicians are gathering, the auditorium stage is ready, instruments are being set down. It’s like any other pre-performance scene, only this evening, the sun having set, some performers are still wearing sunglasses. And those who are, also speak from behind face masks.

The musicians range from amateur to professional, and all initially met over the social media app Telegram, the go-to method of communication during this summer and autumn of unrest, uprising and violence across Hong Kong. And just as they would conceal their identity during an anti-government protest march, so they will on stage, for tonight’s free orchestral performance of Les Miserables.

“Playing music is one of the most peaceful forms of protest,” says C.T., a soprano. “Lots of people don’t know how to contribute to the movement, so this is one way.”

The performance reaches a crescendo as those on stage segue from the trials of Jean Valjean to a rendition of the city’s new, de facto anthem, Glory to Hong Kong. All in the stadium are on their feet, swaying their smartphone lights as they join in with the chorus.

Tonight’s performance is a salve for six tense months of turmoil, but it is also part of the one constant theme of the unrest, a prevalent feature at and between protests; from the primordial rhythm of chants along Hennessy Road to hymns at Chater Garden rallies and lunchtime choral outbursts in malls, music has remained the connective tissue for Hong Kong’s leaderless movement now charging into the new year.

It is hardly a new phenomenon. Music has played an intrinsic role in strengthening protest movements worldwide, from apartheid era South Africa to “the singing revolution” that led Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania to break the yoke of the Soviet Union.

Protest music has been integral to pop music’s greater lexicon as well, providing cultural record of historic struggles such as Billie Holiday’s 1939 rendition of Strange Fruit, a haunting ballad using fruit hanging from a poplar tree as a metaphor for lynched African-Americans. From the folk songs of leftist icon Woody Guthrie to rapper Kendrick Lamar being chanted at Black Lives Matter rallies and MILCK at the 2017 Women’s March.

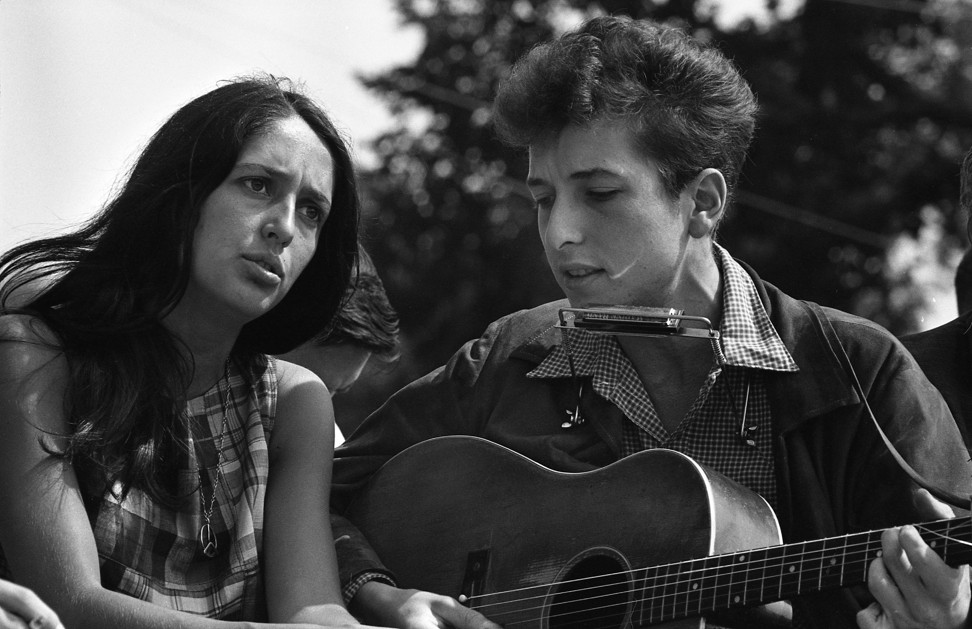

Bob Dylan was one of the most prominent protest songwriters of the 20th century. HisA Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall (1963), Only a Pawn in Their Game (1964) and Blowin’ in the Wind (1963) fuelled rally morale from voter registration protests in Mississippi to the march on Washington for jobs and freedom in 1963 and anti-Vietnam war rallies alike.

“Voices joined together can have immense force, visually as well as sonically. Music is a way of claiming or inhabiting a public space,” says ethnomusicologist Caroline Bithell. “Mass singing allows people to stand up for a cause without engaging in violent or illegal activity.”

Bithell, a professor at Britain’s University of Manchester where she teaches political activism and identity through music-making, says, “Music in itself can be a powerful and intense experience often leading to a sense of euphoria. This effect is intensified further when music is allied with a cause about which people feel passionate.”

A Hong Kong musician and ex-lawyer, who uses the alias GoDareShe, says of this summer’s aural landscape, “Music is to do with vibrations and it travels deep into your physical being. During protests, of course you don’t get sophisticated harmonies, but if you have 1,000 people singing the same song, your vibrations multiply 1,000 times.”

During Hong Kong’s 2014 “umbrella movement”, songs such as Do You Hear the People Sing, from Les Miserables, became the soundtrack on the streets, while this summer saw a performer playing the Korean protest song March for the Beloved, an anthem that commemorates those who were massacred by paratroopers and police in the May 1980 Gwangju democratic uprising. It was also prominent in the June Struggle of 1987, which ultimately led to democratic reforms.

“Those who sing these songs today might be reminded of all those who have sung them before,” Bithell says. “This creates an even stronger solidarity through a sense of shared history, as well as optimism, with the knowledge that music has made a difference in the past and can do so again.”

When examining what makes a successful protest song, Mark LeVine, professor of modern Middle Eastern history at the University of California, in the United States, suggests there are several elements. “Like any other song, it needs to be catchy, it can’t be too complicated and it needs to have a pulse that is easy to follow. It can’t be too fast and can’t be too slow. It has to be an earworm; something that is repeatable and you can’t get out of your head. And it has to have a message; the more you say it, the more it becomes part of your political personality,” says LeVine, who was recently in Hong Kong and “saw how powerful the chants were”.

“Repetitive patterns in both lyrics and melody are common,” Bithell agrees. “This helps to make the song more memorable and easy to learn and at the same time it reinforces the message. A good example is Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ in the Wind, built around the rhetorical question, ‘How many … before/till … ?’ and culminating in hard-hitting lines such as ‘How many deaths will it take till he knows that too many people have died?’”

What Dylan changed was that through “the sound of his voice [it] became possible for popular music to cover the full range of emotions. [It was] no longer limited to sounding nice,” says Alex Lubet, a professor of music at the University of Minnesota, in the US. “He had a particular influence on African-American popular music, in part because of his anthemic contributions to the civil rights movements but also on individual artists.”

Global struggles often reflect local music traditions. Chile’s recent protests saw mass assemblies of guitar-wielding marchers, strumming activist and folk revivalist Víctor Jara’s exquisite ballads. While his music lives on in the streets of Chile’s protests, Jara himself was killed when dictator Augusto Pinochet’s soldiers tortured and shot him more than 30 times after the 1973 coup.

More Western protest artists are internationally known due to their commercial success; both Lamar and Dylan have been awarded the Pulitzer Prize. MTV even has an awards category for the Best Video with a Social Message.

While Lubet agrees that political songs are “part of the American identity” he also acknowledges that “the other great influence on rock was the Beatles who also wrote topical songs and were arguably more activist than Dylan, especially John Lennon in the anti-Vietnam war movement and Paul McCartney in animal rights. The UK has also produced the Clash, the Sex Pistols and Billy Bragg. Ireland is the home of U2”. All of these artists incorporate themes of activism, anti-establishmentarianism or solidarity with the disenfranchised in their music.

Digital technology has also fundamentally transformed the production and dissemination of protest music, enabling people to memorise songs before coming together in a physical space.

German band Atari Teenage Riot have been creating anti-Nazi and anti-fascist electronic music since the early 90s. The video for their 2011 track Black Flags, from the album Is This Hyperreal?, is a montage of clips taken during protest movements and features rapper Boots Riley, who was active in the Occupy Oakland protests.

“We came up with an idea where our fans could film themselves singing along to the song and then send clips and we would edit them together,” says vocalist Alec Empire. “Not a great idea in itself, though in 2011, these things were not yet that common. Suddenly things took an interesting turn.”

Occupy Wall Street supporters and groups fighting censorship and surveillance pushed the song online and Empire’s inbox filled up with footage shot by activists at protests globally. A third version of the video includes a contribution from WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange.

“The video morphed from a viral fan video to a music documentary that reflected what was happening with these protests on the streets and online,” Empire says by email from Berlin.

This digital crowdsourcing technique was also used by Belgian initiative Sing for the Climate in 2012. Recordings of 380,000 voices at gatherings in more than 180 cities were synthesised into one video. Likewise, Glory to Hong Kong was produced collaboratively by various independent musicians.

Numerous cover versions involving instruments as diverse as the piano, bagpipes and even a musical-calculator were uploaded to YouTube – allowing the song to extend its reach.

One such YouTube video, which has garnered more than 700,000 views, shows busker Oliver Ma defiantly playing the English version of Glory to Hong Kong while being surrounded by police officers. At his Po Lam flat, Ma says, “Glory to Hong Kong is the song that makes people here the most emotional right now. People cried in front of me, or offered me a hug. It is touching because they relate to this song a lot.”

“Singing on the streets itself was a novel experience,” says GoDareShe. “In Britain, everyone sings every week at the football stadium, but we don’t have that – we got to experience that in protests.”

The song has a national anthem-like melody that connects with the desire to reinforce a Hong Kong identity. The military beat allows it to circulate easily, and the specificity of the lyrics made Hongkongers embrace it.

“A song is most relevant when it doesn’t just have that emotion of rebellion but directly addresses the phenomena that we have witnessed in the current political climate,” says GoDareShe. “In every political protest you have some wounds, resentment or complaints. You can sing an Olympics song about reaching for your goal and that is also empowering, but it doesn’t touch on the frustration or the fight against people in authority who are abusing their powers. If you can combine these two, it will move people the most.”

Folk singer-songwriter Ryan Harvey, one of the many artists who gathered in New York’s Zuccotti Park during 2011’s Occupy Wall Street, was “not trying to write a vague anthem song. I write songs that are extremely specific. Back in the day, the reason a song existed was to sing together and share a common moment. I’m writing songs for people who might be listening to music rather than reading a book.”

Harvey launched Firebrand Records for “radical political artists” with Rage Against The Machine guitarist Tom Morello. Their line-up of international talent includes French-Chilean musician Ana Tijoux and Ramy Essam, who was a prominent musician at Tahrir Square during the 2011 Egyptian revolution.

Bithell says songs don’t necessarily have to have revolutionary lyrics: just the act of hundreds or thousands of people singing together can be seen as an “empowering and emancipatory” political act.

This can be seen in the prevalence of Sing Hallelujah to the Lord over the summer, where pastor-led singing sessions permeated the streets of Hong Kong. The hymns were part “spiritual weapon” and part demonstration of the importance Hongkongers place on religious liberties. Christian Hongkonger K. says, “The song is a peaceful way for Christians to say that the Lord in Heaven is the actual ruler of our world. The Communist or Hong Kong government, or the police, are basically nothing in comparison.”

While many people were surprised by the singing of hymns at Hong Kong’s gargantuan protests, composer Byron Au Yong, who hosts protest-song workshops in the US, says, “Churches were organising spaces for the civil rights movement in the United States. Singing religious songs makes sense as they are constructed to bring people together in celebration, hope and prayers.”

In another use of orchestral activism, Au Yong’s work Occupy Orchestra 無量園 Infinity Garden uses “sonic tactics” inspired by the 2011 Occupy movement, such as the “People’s Microphone”, where people repeat what a speaker says to amplify the words acoustically throughout a crowd.

“We discussed how to address economic, environmental and societal inequities,” says Au Yong. “At the same time, orchestras around the United States were going bankrupt and closing. Occupy Orchestra provides a way to consider the role of a large musical ensemble [that has been] displaced and deemed no longer relevant by advanced global capitalism.”

The piece references the classic Chinese garden, a space with which Au Yong draws parallels with Occupy rallies in parks. “Historical Chinese scholars and political dissidents gathered in gardens,” Au Yong explains. “Unlike Japanese gardens, to be observed from afar, Chinese gardens were intentionally designed as chaotic to allow people to discuss political turmoil and easily disappear, if needed.”

Aware of the power of protest music, authorities often hold a particular disdain for songs that express political dissent.

Atari Teenage Riot have performed at numerous rallies and their performance at a Berlin May Day protest against the Nato bombings of Kosovo in 1999 descended into chaos when band members were arrested.

“We were asked to perform at the protest and we wanted to support it,” Empire says. “At one point, the police started attacking protesters with sticks and threw tear gas into the crowd – the strategy was to break it up. The video material that was later used in court against the police clearly shows that peaceful protesters were attacked. Some of them even held up their hands but they got beaten anyway.”

During Tunisia’s jasmine revolution of 2010-11, which led then-president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali to flee the country, folk and hip hop music helped galvanise support.

Tunisian rapper El Général’s scathing track Rais Lebled, which he describes as “a beautiful gift” to Ben Ali, became one such soundtrack to the uprisings that overthrew the government. In it, El Général addresses state corruption, waxing lyrical about police violence, starvation and the misery of citizens.

Hip hop was a weapon that I used to defend myself and the causes I care for, like the Tunisian cause, the revolution

“I knew that since the 70s rap has been revolutionary and that is the basis on which it was created,” El Général said of his use of hip hop, during an interview in his hometown of Sfax in 2011. “It became commercialised but the origin of the musical format was to defend people and to talk about their problems, such as racism.

“Hip hop was a weapon that I used to defend myself and the causes I care for, like the Tunisian cause, the revolution. I could have sung another style of music that was less political, but I wanted to have this socially engaged personality, fighting for real problems.”

With El Général’s release of Tunisia, Our Country the then 21-year-old was promptly arrested, handcuffed and interrogated. His much-publicised detention, however, made El Général a celebrity and his provocative rapping gained him a spot on Time magazine’s most influential list for 2011.

Another “official” response to protest music can come in the form of a government releasing its own songs – often with embarrassing results. Recently during the Hong Kong protests, Chinese propaganda rappers CD Rev released a track titled Hong Kong’s Fall that describes “1.4 billion Chinese standing firmly behind Hong Kong police” and goes on to says the Chinese People’s Liberation Army is waiting to “wipe out terrorists”.

“They would likely be repeating themes that the state are trying to impress on the people, themes that are under threat,” LeVine says of the propaganda music.

“If it is in response to protests, they are being made in semi-desperation so it might be very blatant and obvious. Generally, you don’t have many of the best artists working with the state. In Egypt, for example, artists supporting [former president Hosni] Mubarak were ostracised when he left.

“When the state gets involved in music production for propagandistic purposes, they put a lot more resources into it than the protesters might have at their disposal. Rais Lebled was a cheap but powerful video, very lo-fi and DIY.”

While LeVine says “bubblegum” music might work in more normal times, during intense political moments, those kinds of songs “can’t hold a candle to even something as simple as [Tunisian] Emel Mathlouthi singing a cappella into a microphone on an iconic boulevard”.

Protest music can escalate a situation, turn a protest violent, calm it down or even turn it into a joke. When you hear music from people who fight for freedom, you can understand that within a few seconds

As Nigerian iconoclast and afrobeat founder Fela Kuti once said, “Music is the weapon of the future,” and Empire agrees: “Protest music can escalate a situation, turn a protest violent, calm it down or even turn it into a joke. When you hear music from people who fight for freedom, you can understand that within a few seconds.

“It’s part of analysing where the cultural zeitgeist is in that moment in time, and how you position yourself as an individual within that. Music only works this way when it expresses real truths.”

Before she steps on stage in Tai Po, C.T. wonders whether there is a “danger” of citizens enjoying the music but not engaging in “further steps”.

Yet as the protests roll into their seventh month – with many suffering from protest fatigue – for GoDareShe the answer is clear.

“Music provokes you into action, it feels like energy,” she says. “You might be uncertain and frightened but when you listen to music you feel like, ‘I might be able to do this!’”