The tiny Atlantic island of St Helena is turning towards tourism – will it be kill or cure?

Once sustained by trading ships as they paused to replenish supplies en route to Hong Kong, and home to Napoleon Bonaparte during his exile, the British territory hopes to reinvent itself as a tourist hot spot

Founded in 1659, isolated mid-ocean 1,930km west of Africa and almost halfway to South America, it is the second-oldest of Britain’s remaining overseas territories after Bermuda. With a population of a mere 4,415, St Helena is just 10km across at its widest point, and about 50 per cent larger than Hong Kong Island, which was annexed by the British almost two centuries later.

On this tiny, sheer-sided volcanic mass the roads are mostly too steep, narrow and winding for regular transport routes. Instead, a shipping container is arriving at the dock in Jamestown, the capital, where its contents of goods will be brought up through a narrow arch in the city’s ancient fortifications, still bearing the arms of the long since vanished British East India Company.

Fresh fruit sells fast here, although prices can be as steep as the hillsides. For the next few days the talk of the island is the appearance of peaches, at £1.05 (HK$10) each; they sell out, even though incomes average only £708 a month.

“We see it happen every time the ship comes in,” says Derek Richards, a resident who runs a sandwich bar inside the grey-and-white Victorian market, which was built in 1865. “Every time the fruit goes on the shelf, people prioritise.”

St Helena was once sustained by British vessels blown in on trade winds and laden with silk, porcelain and tea, as they paused to replenish supplies between Hong Kong and Britain. The advent of the steamship and the opening of a shorter route via the Suez Canal, in 1869, put an end to all of that.

In one of the most remote inhabited places on Earth, “the agricultural industry needs a pretty good shot in the arm”, says Dr Philip Rushbrook, the island’s dapper, silver-haired governor. “In the past we used to service 1,000 ships a year – sailing boats – but now we can barely grow enough potatoes.”

In 2002, a referendum on the construction of an airport for the island rendered in a narrow “no” vote. Some viewed air links as offering economic salvation, others foresaw an end to the island’s close community of equals. Despite the rejection, the airport went ahead anyway.

“I wasn’t here at the time,” says Rushbrook, seated in his office in The Castle, a semi-fortified cluster of administrative buildings dating back as far as the early 18th century, which he has occupied since May last year. “But the quite simple decision that had to be made – and it wasn’t just an island decision, it was a British decision in the UK – was that the RMS was coming to the end of its economic life for its purpose then.”

Just as in pre-handover Hong Kong, St Helena’s governor is a London appointee working with Legislative and Executive councils, although unlike in Hong Kong, St Helena’s Legco is elected by universal suffrage.

The much-loved RMS St Helena was a combined passenger and cargo vessel, the island’s only scheduled link to the outside world. The airport was seen as essential to broaden and diversify the economy, and as Rushbrook explains, Britain retains the right to make decisions in public security, defence, foreign affairs and international access. So London made it happen, with construction beginning in 2012.

All conversations on the island lead back to the airport sooner or later, and if there’s one thing an outsider might know about St Helena, it is that the British built the facility for a tiny population at the vast cost of £285 million. It then could not be opened to commercial aircraft for 18 months due to wind shear problems, as many a St Helenian wiseacre claims to have predicted.

The airport, which opened in 2016, was meant to transform the island’s sleepy economy, but it did so in ways that had not been anticipated. Saints, as the St Helenians like to call themselves, often spend one or two decades working on Ascension Island, several hundred kilometres to the north, or in the Falkland Islands, to the west, where salaries are better.

They returned in significant numbers to work on the airport’s construction, and the additional arrival of assorted foreign contractors and consultants sent rental and property prices soaring as demand exceeded supply, leading first to a rapid increase in house building, and then to a headache for the government after the airport was completed.

“Now the building boom has passed there’s been a reluctance among people to reduce the price, because over the five or six years during which the airport was built it was seen as a comfortable income,” says Rushbrook. “But now there isn’t that demand for housing, particularly from outside contractors and consultants and engineers coming onto the island.”

“I’d like to write a paper on how rational economic theory doesn’t seem to work here,” says Nicole Shamier, another British import and the island’s chief economist, although her remarks on how a tax on empty properties would be hard to introduce provide a partial explanation of housing supply and demand. “The culture here – almost like the St Helenian dream – is to be able to own your own property. So messing with that dream in any way, putting up any barrier to that dream, is a complete no-no in terms of the electorate.”

The real reward for spending so many years working overseas is to build a house to come back to.

The stance was that you need to be more welcoming to people who want to invest here

The memorandum of understanding authorising the airport expenditure included many provisos for modernising the island’s economy.

“The stance was that you need to be more welcoming to people who want to invest here, because why would we fund an airport if you’re then going to turn away anyone who tries to make the island self-sustaining,”says Rushbrook.

Tax relief for investors, minimum wages, sick pay, maternity leave and other measures were introduced as part of a thorough modernisation of the economy. But the most seized-upon benefit was the prospect of 30,000 visitors a year.

So it was a disappointment to many that in the past three years annual foreign tourist arrivals have only risen from 357 to 1,295.

But in the business case for the airport, that 30,000 figure was set to be achieved by 2042, and the growth so far is more or less on target. Today, more importance lies in increasing the export potential of top-end goods unique to the island: sashimi-quality cuts from local tuna, St Helena’s expensive Green Tipped Bourbon Arabica coffee, for which international demand exceeds supply, and premium honey from its unmedicated and disease-free bees.

“I think a lot of people never read the small print,” says Rushbrook, “and they based their investment decisions in new accommodation, new restaurants, more hire cars or whatever on the big number in the future and perhaps lost track of the idea that this would be a slow burn as we build up knowledge of the island and you get tour operators interested.”

There are good reasons why tourism should grow. The island is home to superb, well-marked walking trails across the crumpled landscape and plenty of knowledgeable tour guides to provide background information on the many important visitors, from Captain Cook to Charles Darwin and the Duke of Wellington. There are towering castles and fortifications with fabulous views, Boer war sights, Georgian Jamestown, and an excellent history museum in an old East India Company warehouse.

But St Helena’s star attraction is Napoleon Bonaparte, who was exiled here after his final defeat at Waterloo. Crowds of St Helenians gathered to view this captive bogeyman as he was brought on shore in October 1815 through a still-visible side entrance in the fortifications. The former French emperor spent his first seven weeks in a green-painted room in the summer house annex to a mansion called the Briars Pavilion, in the valley above Jamestown, now restored to its early 19th century condition with furniture of the period based on descriptions left by his entourage.

The pavilion’s guide provides Napoleonic anecdotes, the gardens are well-tended, and it is a pleasant spot despite the occasional sounds of nearby light industry. But even this has a certain authenticity. Napoleon would have had to live with constant repairs and the building of extensions after he moved a short way inland to Longwood House – converted farm buildings that had become a summer residence for governors. Here, he and most of his 28-strong retinue crowded into a small warren of rooms.

The French tricolore flaps above ornate gardens of tropical brilliance in whose design Napoleon personally took a hand, and the house displays many of his original furnishings. A billiard table brought from England dominates the first room although he did not take to the game and covered its baize in maps while he relived past campaigns and dictated his memoirs. Vast terrestrial and celestial globes occupy one corner.

Signs warning against touching artefacts or sitting on furniture almost outnumber the historical items themselves. Staff pad watchfully behind visitors as if to ensure that they do not pocket the spoons, and to forbid photography of any kind.

The atmosphere is one of genuflection. The house guidebook, without irony, describes the drawing room where Napoleon died, even its original wallpaper of ivory with blue stars now recreated, as the “holy of holies”. The room in which Napoleon was laid out after his death is still hung with black fabric.

Napoleon would undoubtedly have preferred Plantation House, now the governor’s year-round residence, built in 1792. It is a pale-blue, two-storey, 35-room mansion on high ground with views to the sea. Its entrance hall is hung with portraits of British royals past and present, and one green corridor displays those of dozens of earlier governors.

All is dignified elegance beneath imported ceilings of hammered metal. A large dining room houses a vast table from the 1800s capable of seating 24, where island coffee and jammy dodgers are served to those who complete the tour of assorted teak-floored rooms.

The most interesting resident here is perhaps not the governor but Jonathan, a Seychelles giant tortoise, 188 years old and thought to be the oldest living land animal, who staggers around the lawn on tree-trunk legs with a few younger companions.

At Napoleon’s former tomb, a short distance west of Longwood, a leafy path leads gently downhill to the head of a valley where the former emperor once liked to walk, and to pretty, well-tended terraced gardens around a blank slab. The British, who treated Napoleon as merely a general, declined to allow the French to carve his name in an imperial style, so it was omitted altogether.

Napoleon’s body was moved to Paris, in 1840, and the French government eventually acquired Longwood, the Briars Pavilion and the Valley of the Tomb, now three corners of a foreign field that are forever France.

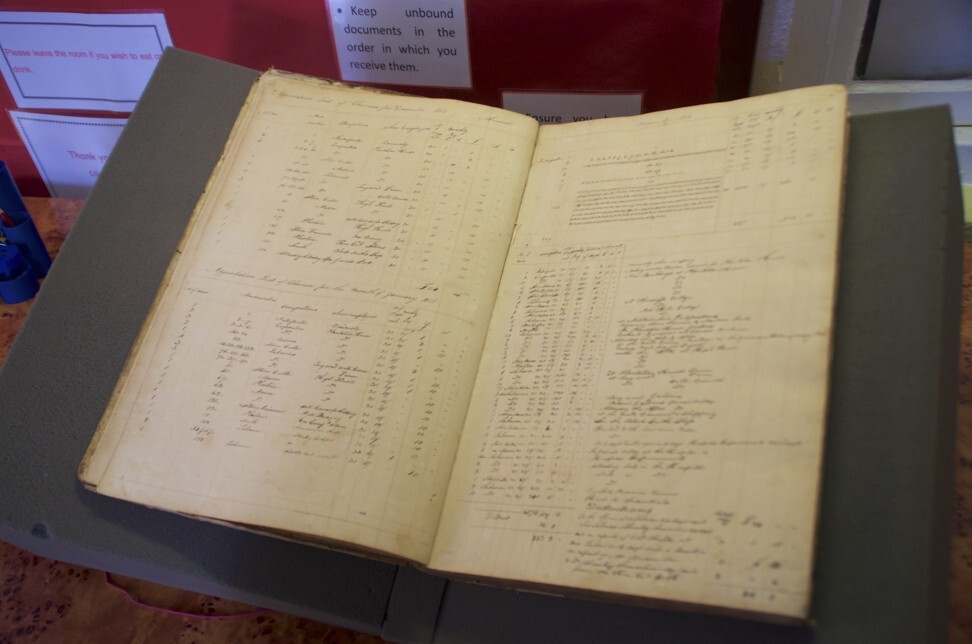

Having had the builders in for nearly six years, Napoleon was possibly glad of the rest, not only from hammering but from the alien sounds of Cantonese, a presence revealed in one dusty volume in the island’s archives: Accounts of Chinese Labour Etc. and Expenses Incurred on Longwood During the Residence of the Emperor Napoleon 1815-1818, which details the payments to Chinese brought by the British to work as carpenters, stonemasons, and agricultural labourers, building fortifications and growing supplies to provision East India Company ships.

Perhaps uniquely among places that once had a significant Chinese presence, there is no Chinatown now, but you will find hints of times past, such as a block over the door to the archives, carved with phoenixes.

In Jamestown, the Orange Tree Oriental Restaurant announces itself in Chinese characters, although the manager’s name is given as 雏菊 (Chújú), a translation of “Daisy”, and it turns out to be Filipino-run. The food is plentiful and served with warmth, but the establishment’s most authentically Chinese quality is the Kenny G playing in the background.

A short walk uphill past the market hall and its clock tower, there’s a sign for China Lane. But the shops that once served the Chinese are as long gone as the Chinese themselves. Their employment contracts ended in 1836 and all but a handful who had prospered and purchased land, or married local women, were returned home.

“Tourism, I think, is going to be niche,” says Rushbrook. He has in mind sectors such as hiking, diving and swimming with whale sharks. The prospects for developing St Helena’s economy in the shorter term lie elsewhere. “No one here, if you ask anyone in the street, is looking for the island to be turned into some sort of Marbella.”

The focus at government level is now on virtual rather than physical connectivity, and the imminent arrival of high-speed broadband internet via a fibre-optic connection to the African mainland.

St Helena’s current charms supposedly include the opportunity for “digital detox”, since although internet access is widely available via satellite, bandwidth is narrow and the cost beyond the reach of many residents. Such internet commerce as does take place, especially that which involves uploading websites or downloading files, happens between midnight and 6am, when the satellite service is free.

Real-time connection to the outside world via cable will make feasible ground stations for satellite monitoring, spacecraft communications, and no doubt spying, using the same geographical advantage that in 1676 brought British astronomer Edmond Halley of comet fame to the island to produce the first map of the southern skies.

But the opportunities arising from connection to the world’s digital economy are rarely mentioned by ordinary Saints. For centuries they have been hearing that new innovations will save the economy and provide jobs, from the introduction of sisal for ropemaking, to flax for linen, mulberries for silkworms, and the airport, a project that was on-and-off for years before construction finally began. So while the cable is due to make landfall in 2021, that will be believed only when it is seen.

The talk in government is now of attracting “digital nomads”. But these are typically found, at least in their own imaginations, on sunbeds hazardously placed beneath coconut palms on perfect curves of white sand, with a cocktail to hand. St Helena has a small distillery and so can do the cocktail, but is rather lacking in all the rest. Despite its year-round moderate climate, this is no dreamy desert island destination, although it is more interesting than most of those.

But the cable, Rushbrook points out, will also allow Saints to make money off-island without actually having to leave.

For now his main concern is with improving how government functions, and bringing about more rapid decision-making while making elected representatives more accountable.

So is he St Helena’s answer to Chris Patten? “No,” he says, earnestly. “The job of the governor is to ensure that the system of government, elected representatives and administrators are running as efficiently and effectively as possible and also are managed as financially tightly as possible.”

The impetus for change comes not from him, he says, but from the general public, and so for them, the tourism infrastructure being built, and the visitors the island hopes to soon welcome, Rushbrook implores all concerned to “be kind to St Helena” .