33 years of changing China as seen through the lens of a Scottish photographer

In his explorations of China, his adopted homeland, teacher turned broadcaster Bruce Connolly documented the country as it underwent extraordinary changes

In the summer of 1986, I completed a circular journey around Scandinavia,” says Beijing-based Scotsman Bruce Connolly, who, then 39, was already a seasoned world traveller. “At the end of the trip, I caught sight of a train from Moscow in Helsinki station; I’d never imagined that you might be able to take a train through the USSR before.”

Connolly had to return to his native Glasgow, where he taught geography at a local high school, but the idea of an eastbound train journey festered during the long, dark months of a Scottish winter. Frustrated and depressed, Connolly headed to the nearest travel agency to see what might kindle some inspiration.

“I was just turning 40 […] I sat in a Glasgow pub and over a beer, browsed the brochures I’d picked up. I soon realised you could go all the way by train from Glasgow Central Station to Hong Kong. I decided to use my summer holiday in 1987 to make the journey. I called it my ‘ultimate dream.’”

Connolly had no idea how profoundly this transcontinental odyssey would change his life, transforming a man who was “entirely ignorant of China” into a passionate Sinophile, who would travel the length and breadth of the country as a photographer, tour guide, radio host, writer and educator. Thirty-three years on, now aged 73, it is a journey he has yet to complete.

Born in 1947, Connolly grew up in Glasgow when “there were still tram cars” and the city “smelled of coal”.

“My family lived quite near the docks where boats came in from all over the world, from Africa and India,” he says. “The people on the ships seemed so different. You heard languages you could never understand. I soon realised there was much more to life beyond the banks of the River Clyde.”

Connolly’s father was local entrepreneur Alex Connolly, who ran a confectionery business. The family moved several times before ending up in the suburbs, which positioned Bruce Connolly well to satisfy his burgeoning wanderlust. “We could see the hills in the distance and I was very attracted to them. It was quite easy to get out into fabulous countryside. Loch Lomond was only an hour away but it was a totally different terrain.”

First with his father and later alone, Connolly would hike and camp in the Highlands. As he explored the wilds of his homeland he became interested in documenting them.

“My parents bought a caravan that was based in Maidens, a fishing village just south of the town of Ayr. Every summer we would go there. That was where I started experimenting in photography. Seagulls, sheep and fishing boats were my early subjects,” he says.

Connolly became an avid reader of National Geographic magazine while shut in the caravan on rainy days. “There was no internet. If you wanted to see the world you looked to magazines. I remember seeing pictures of Lhasa and Ulan Bator and thinking, ‘I’ll never get there.’”

But the magazines inspired Connolly to up his game as a photographer. “I persuaded my father to buy me a Kodak. It could take colour transparency film such as Kodachrome. Film was expensive and it required a projector to view, but it was a start.”

It was perhaps inevitable that Connolly would study geography, first at the University of Strathclyde and then at postgraduate level at the University of Glasgow, before becoming a teacher in 1972. “I always took students on outdoor activities,” he says. “I really wanted to combine classroom teaching with field work.”

Connolly had been a train buff since the 1950s, when his mother, Claire, would take him on regular visits to Manchester aboard “corridor steam trains”, he recalls. “On a train, you can sit back, relax and meet the people.”

But the limits of Britain’s network soon grew evident. “In the UK, there’s not so much of an experience because the journeys are too short. But on long journeys in the United States or Canada your train becomes a little world from where to view the wider world changing beyond.”

North America was then the dream destination. In the summer of 1981, Connolly finally flew to New York and travelled by train to California. This first “big adventure” would steer him to a secondary career in broadcasting.

“When I got back to Scotland, I was asked to give a short talk to the Royal Scottish Geographical Society about my trip. A colleague who worked with a Saturday morning programme on BBC Radio Scotland mentioned me to the editor, the late Murdoch McPherson, who asked me to come into the studio. I was extremely nervous but the host, Ross Finlay, literally took me by the hand. We recorded enough material for a miniseries, six episodes in all,” he says.

Connolly would be drawn back to North America another three times, travelling to the Deep South, Alaska and taking the trans-Canadian railway from Nova Scotia to Vancouver, returning with stories to captivate radio listeners. But when he set out in the opposite direction, in 1987, his life would be permanently reorientated.

Connolly had been on the rails for two long weeks by the time he reached Beijing, travelling clear across Russia – a landscape he describes as “repetitive”, “flat land and forests” – followed by the grasslands of Mongolia and “the first signs of Asia […] yurts and nomads on horses”.

But it was south of the Gobi Desert, when the train entered a “busy and dynamic landscape”, that the view began to animate Connolly’s imagination.

“I had no great preconceptions about China. If anything, I imagined it to be like neon-lit Hong Kong, which was the only kind of China we ever saw in the UK. But what I saw amazed me,” he recalls.

Touring the “extraordinary” sites of the Chinese capital, from the Great Wall to the Forbidden City, Connolly was seduced. “It was the bustle that grabbed me. I realised this was an amazing place. Everyone was immensely curious and friendly. But it also dawned on me there were a billion people on Earth I knew next to nothing about.”

After a three-day layover, the train forged south towards Guangzhou. “I remember early in the morning there was a beautiful sunrise over the Yellow River. Stations were full of human traffic, full of life. People were selling food from carts, there was just so much activity.”

From his window Connolly watched the landscape change from the arid central plains to the verdant south, as he crossed a “spectacular” Yangtze River bridge and entered “subtropical China”.

After a brief stay in Guangzhou’s White Swan Hotel, overlooking the Pearl River, “the first taste of luxury in weeks”, Connolly continued on the final leg of his odyssey. “The journey between Guangzhou and Hong Kong went mostly through agricultural land, duck farms and fruit plantations. We were rolling along when I saw these big modern buildings. I thought we’d arrived in Hong Kong early,” he says.

In fact, Connolly had reached Shenzhen, ground zero for Deng Xiaoping’s experimental reforms. The sight of mainland China’s first skyscrapers and multi-laned boulevards triggered an epiphany.

“It was a wake-up call. I thought. ‘Good grief, China is going somewhere. If I don’t photograph some of this now, it’ll be gone.’”

In the years that followed, Connolly’s “ultimate dream” turned into an obsession. He read everything he could get his hands on about China and spoke about it on the radio and at public events, all while hankering to return to a country that was not yet entirely open to foreign travellers. Eventually, an opportunity landed in his lap.

“The Strathclyde Regional Council had twinned with Guangdong and wanted people to go there on an educational exchange programme aimed at helping English language training develop. I was not an English teacher. But I got an interview and it turned out I was the only person who’d been there. And also, because I’d been doing a lot of reading, I knew what I wanted to do – that is, get a deeper understanding of China.”

Connolly was selected and arrived in Hong Kong one sultry summer’s day in 1992 armed with a year’s teaching contract and his trusty camera. Rolling into Guangzhou’s chaotic station some days later he was struck by the cordial reception he received.

“My colleagues came to greet me and helped me with my bags. And then, when I went to the classroom, the students gave me a round of applause and sang the teacher’s song. Then they all sat down. Total silence. They were waiting for me to start teaching.”

Guangdong Foreign Languages Normal School was a leading college and Connolly’s students quickly impressed him. After 20 years as a teacher, they helped rejuvenate his passion for teaching, which had been waning in Scotland. “People wanted to learn, there was no messing about. They had ambitions,” he says.

Compared with Zhujiang New Town today, with its cocktail bars and rowdy expat dives, there was little in the way of foreign entertainment in early 90s Guangzhou.

“The only Western-style bar was in The Garden Hotel,” says Connolly. “But I spent most of my time walking beside the Pearl River. There was constant river traffic, boats going upriver to Wuzhou or downriver to Zhongshan. It was fascinating.”

Connolly also got lost in the city’s older boroughs, many of which have since been demolished. “There were so many alleys down by the riverside. I tried to learn about Guangzhou and its place on the Maritime Silk Road by walking it. And, of course, I took a lot of pictures.”

Some of Connolly’s most dazzling images from the period were taken during trips around the Pearl River Delta. He went south to document Shenzhen’s growth and photograph China’s first McDonald’s, which opened in Luohu in 1990, and northwest to shoot the karst mountain city of Zhaoqing, where he was invited to ride a steam train along the newly constructed Sanmao Railway.

Across the Pearl River, a friend named Linda took him on a tour of her hometown, Taishan, in Guangdong, which had helped forge the Chinatowns of the world since the 19th century. There, Connolly shot the distinctive East-meets-West, turn-of-the-century architecture of China’s deep south, as well as the bucolic villages of “the land of the rice fields”.

But it was on a Lunar New Year trip to Hainan Island that he produced his most breathtaking work.

“In those days it was very difficult to get train tickets, especially around Chinese New Year, when the migrant workers all went home. A friend suggested I go to Hainan as very few people went there at the time. So I took a ferry from the terminal near the White Swan Hotel. It took 24 hours to get to Haikou [the capital], where I stayed for a few days. Then I took a bus to Sanya [in the south].”

Today, it is a veritable Chinese Miami, with luxury seaside resorts and golf courses, but, when Connolly got there, Sanya was untouched by China’s commercial revolution.

“I found a local hotel by the beach, where I had to show my employment documents just so I could get a room for the night as there were no foreign tourists. I then walked across the sand past old wooden shacks. It was the traveller’s dream: an untouched tropical island paradise.”

If the coast was a bit Robinson Crusoe, a bus trip to the interior took Connolly into a tribal realm so far removed from the modern world it was like walking into a Joseph Conrad tale. “I went to Tongshi, which was still populated by Li and Miao people who lived in villages of adobe thatched cottages.

“There were no maps. I was walking into tropical rainforests on my own. I probably took more pictures there than I took in the whole of the rest of Hainan. I still remember the sun glowing over the paddy fields, the farmers bringing the buffaloes in and the local folk songs drifting with the breeze through the afternoon air.”

When he completed his teaching obligations, Connolly reluctantly returned to Glasgow. But his heart belonged to China and he would return annually, travelling by rail to all four corners of the Middle Kingdom.

“I went to Lijiang to photograph the Naxi minority people,” Connolly says. He describes a Yunnan town of cobblestone roads and wood dwellings that, much like the Li and Miao villages in Hainan, existed largely off the tourist radar. “I remember they opened the airport two days after I arrived and I thought to myself, ‘This place will change.’”

In 1997, Connolly retired from teaching to explore China full time. By then, the country was far more open to tourism than it had been when he’d first visited a decade earlier.

“I spent some time catching up with old friends in Guangzhou then set off on a three-month overland journey to the Lake of Heaven, in Xinjiang. I explored the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and travelled extensively in Yunnan. For a time I was just enjoying the freedom of not having a job after 25 years in the same profession.”

Whenever Connolly visited Beijing he would stay in Beixinqiao, Dongcheng district, near the heart of the walled Tartar city. He became seduced by the hutongs, the alleyways that snaked through communities of Ming and Qing vintage.

“Beijing was unlike Guangzhou. It was yet to take off economically and remained very traditional. I loved just wandering the old streets with my camera, getting to know the city’s history from the Mongol origins to the present day. Eventually, a friend found me a courtyard house near Nanluoguxiang, which was, for me, a dream home.

“I started writing about my experiences for Beijing Today, the China-Britain Business Council and China Daily. I also led study tours for the Royal Scottish Geographical Society and Scottish school groups, among others. I was on one such tour in Shanghai, in 2004, when I was contacted by Radio Beijing and asked to come to the station when I returned.

“I had done some work for them before and we had a relationship. But what they wanted from me was something new: a daily, English-language feature. This became ‘Bruce in Beijing’, a segment in which I explored the city on foot and interviewed just about everyone and anyone. It ran for 12 years, during which we made over 4,000 daily features.”

By 2016, Connolly had called Beijing home for the better part of two decades. Married and settled, he had become, by his own reckoning “part of the furniture”. And he had enjoyed a front-row view of China’s momentous rise. But the urge to travel had not yet faded, even having turned 70.

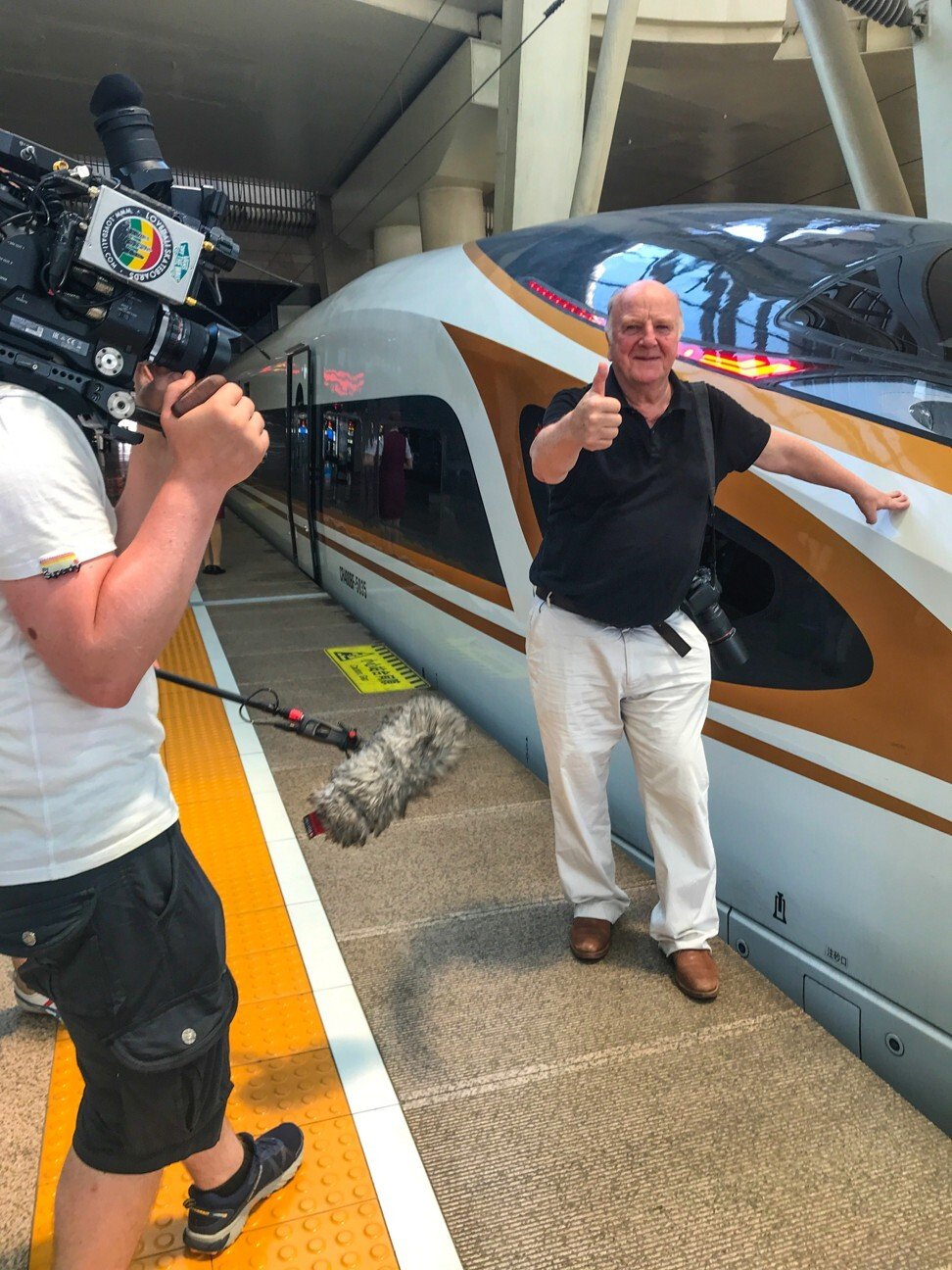

“I wanted to rediscover China and after I finished the radio show I began to take train trips again, this time on China’s incredible high-speed trains.”

One trip took him to the neighbouring port city of Tianjin, which Connolly describes as “a city of layers” best navigated on foot. “I initially stayed in a 100-year-old hotel and walked through the concession areas that had once been inhabited by the colonial powers. There are French, Italian, German and British buildings.”

Yet despite this cosmopolitan legacy, Connolly finds a unique sense of civic identity among Tianjin’s denizens. “It’s different from a lot of big cities in China because, unlike, say, Beijing or Shanghai, most people are local, they’re Tianjiners.”

With regular social media posts and articles for China Daily, Connolly’s Tianjin adventures soon attracted attention. “BBC Scotland made a documentary called Scots in China, hosted by Neil Oliver. In the film, I introduced Tianjin,” Connolly says.

The television appearance and local exhibitions led to his being invited to participate in Inspire Tianjin 2020, a project coordinated by a European friend. He was just getting stuck into the project when the Covid-19 outbreak sparked a nationwide lockdown.

“Tianjin was not hit too badly,” he says. “In fact, stuck in my hotel room, I had a lot of time to scan and edit many of my old photos of China.”

He is far from the only person to have taken the pandemic as an opportunity to look back and assess his life, movements and contributions. “You know, when I look back,” he says, “it’s looking back at history.”