Inside the private Chinese art collection of Joseph Hotung, Hong Kong property magnate, which has been hidden from the public gaze for decades – until now

- While much of Joseph Hotung’s collection of Chinese jades and Yuan and Ming dynasty porcelains is already on display, now his private cache is coming to light

One fateful day in the early 1970s, Joseph Hotung’s flight leaving San Francisco was delayed. With two hours to spare before heading to the airport, the then forty-something Hong Kong businessman wandered into an art gallery, where he became suddenly, instantly enamoured by a pair of translucent, identical jade bowls.

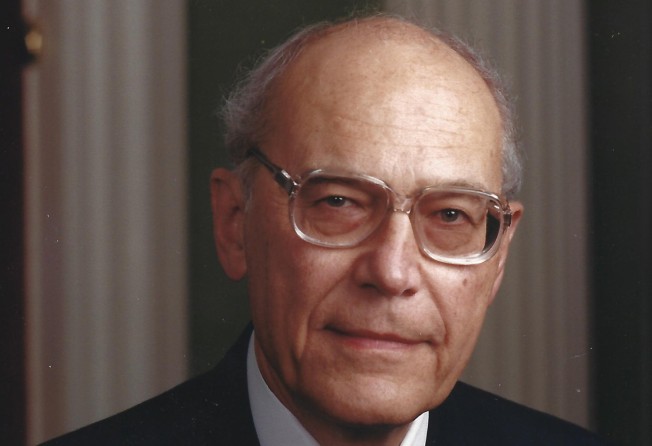

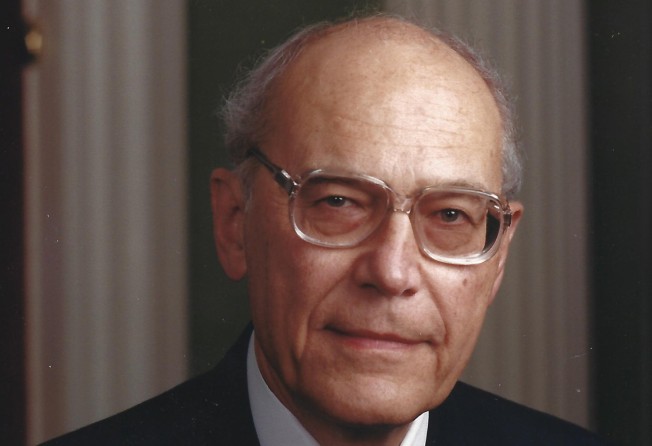

Born into one of the wealthiest Hong Kong families, Hotung followed a career path in property and investment, until his Bay Area jade encounter.

After buying the matching Qing dynasty (1644-1911) pieces, he quickly became an avid art collector. Before long, he was known in cultural circles for his extensive Chinese jade collection and, by 1993, as a global arts benefactor and philanthropist, he was knighted by Britain’s Queen Elizabeth.

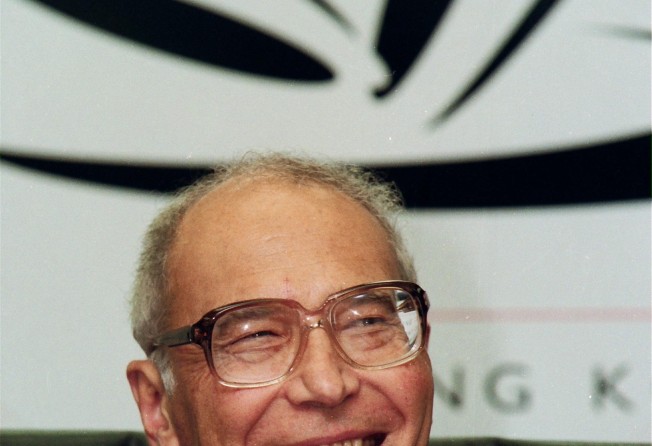

Recalling that serendipitous day in San Francisco, Hotung told the South China Morning Post in 1996 that discovering jade “has been fascinating because it’s given me a totally new interest in life, and a new dimension”.

While as a public collector, Hotung’s affinity for jade was never hidden – many of his pieces are on display at London’s British Museum, where three galleries, including China and South Asia, are named after him – his private acquisitions were another matter.

For decades only his family, inner circle and personal guests at his homes knew which pieces he had kept for private appreciation, and why.

But now, following his death at the age of 91 in December 2021 in London, his private collection is being revealed to the public for the first time.

In what is considered to be one of the most valuable collections of art bequeathed to a British institution, 246 Chinese jades, 15 blue-and-white Yuan (1279-1368) and Ming dynasty (1368-1644) porcelains, 24 bronzes and other items of metalwork, a Neolithic (8,000-3,000BC) white pottery jar and a dry-lacquer head of a Bodhisattva will be donated to and displayed at the British Museum.

Meanwhile, more than 400 other works, including Ming dynasty huanghuali (yellow flowering pear wood) furniture, Chinese ink paintings and a series of Impressionist paintings, were split across two Sotheby’s auctions.

The Hong Kong sale, held on October 8 and 9, brought in a total of HK$563.6 million (US$72 million) while it is estimated the London sale, to be held in December, will bring in £18 million (US$20.4 million) to £26 million.

“Although part of his collection is well known – that is what’s going to the British Museum – the things [for the sales were] hidden,” says Henry Howard-Sneyd, chairman of Asian Art for Europe and the Americas at Sotheby’s.

“People may remember [some of these private pieces] from 20, 30 years before, when they came around in the marketplace. But other than a very, very privileged few, nobody knew what he had.”

Those who are familiar with Hong Kong history will know the name Hotung. Joseph Hotung’s grandfather was Robert Hotung (1862-1956), often referred to as the “grand old man of Hong Kong”.

The illegitimate son of a European father and Chinese mother, Robert rose from poverty to become, at one point in time, the wealthiest individual in Hong Kong, building his influence as a comprador for trading companies Jardine and Matheson & Co, and through his own investment and property endeavours.

In 1906, he and his family became the first and only non-Europeans to be allowed to live on The Peak, Hong Kong’s most expensive neighbourhood.

Later generations continued Robert’s legacy, becoming influential tycoons and philanthropists.

In more recent times, billionaire Eric Hotung – Robert’s grandson and Joseph’s brother – made headlines before his death in 2017 for his financial prowess, diplomatic work and a colourful personal life that involved a decades-long love affair with his cousin Winnie Ho Yuen-ki.

Joseph, on the other hand, lived a quieter life that saw him recognised mostly for his philanthropic endeavours and his jade.

Born in Shanghai in 1930, Joseph Hotung grew up between mainland China and Hong Kong. The Eurasian then spent his two final high-school years in northeastern China, studying at a small Jesuit boarding school in Tianjin, from 1948 to 1949, before moving to the United States and receiving his undergraduate degree from the Catholic University of America in Washington DC.

He would go on to spend a year at Harvard Business School, complete a master’s degree in statistics at New York University, and earn a bachelor of laws from the University of London by taking classes through the University of Hong Kong.

The passing of both his grandfather and father, Edward, who died within a year and half of each other, in April 1956 and July 1957, respectively, prompted Hotung to return to Hong Kong. At the time, he was working for the Marine Midland Bank (fully acquired by HSBC in 1987) in New York and he had planned to return to the US after settling the estate.

But his life took a different turn. “After being back in Hong Kong, he decided, with much trepidation, to try his hand in real estate development,” his daughter Ellen Hotung says.

“Although he did very well, he [grew] tired of the constant volatility of the Hong Kong real estate market, and eventually he diversified the assets to the US and the UK.”

With a slim frame and blue-green eyes, Joseph Hotung was often seen immaculately dressed in his signature look of a grey suit, a crisp dress shirt with colourful bold stripes and an Hermès tie. His voice, tinged with a slight British accent, was soft and mellifluous.

“Though people loved to be in his company, he never looked to be the centre of attention,” says Ellen.

“Privately he was extremely funny. He had a dry wit and could deliver a line that would leave you in stitches – full of anecdotes about his boyhood in Shanghai and our family history.”

“I remember being, as a young man in the field, in considerable awe of him,” says Howard-Sneyd of meeting Hotung for the first time at a Sotheby’s auction in around 1989. “But he wasn’t scary.

“He had an aura, but not something that made you frightened of him, just something that made you respect him immediately.”

By their first meeting, Hotung was already well known as an art collector, but back in the 1970s, his purchase of the two Qing dynasty bowls seemed rather out of character, especially since the businessman had not previously displayed any overt interest in collecting Chinese art.

Enthralled by the history of Chinese jades, Hotung cultivated this new interest by conducting extensive research and amassing a collection of pieces from notable dealers and numerous auctions, including a 1979 Sotheby’s sale in New York.

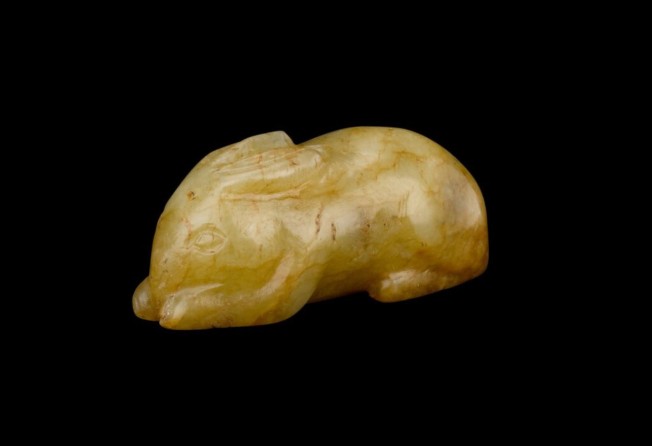

The jades dated back to the Neolithic period all the way up to the Qing dynasty – “the entire gamut of the extraordinary jade history of China”, says Howard-Sneyd.

When Hotung started collecting jades, Ellen was a teenager growing up in Hong Kong. She has fond memories of sitting with her father in his Hong Kong library and opening up small paper packages of centuries-old jades he had bought.

“He would admire the craftsmanship and comment on the hours it would take to painstakingly carve these incredible pieces,” she says.

“He would marvel at how advanced the Chinese were compared with other cultures. I think he was just in awe of these artists and what they were able to achieve.”

To wit: up until the 1970s, jade pieces were not “carved” in the typical sense of the word, Hotung told the Post in 1996.

Because jade is considered a hard stone – it ranks between six and seven on the Mohs hardness scale, according to which talc is one and diamond is 10 – artisans had to use even harder stones to wear it down.

Garnets, sand and carborundum in a paste form were employed to grind the jade by hand and achieve the desired shape.

“As well as being beautiful, it’s also a very tactile stone,” Hotung said at the time, speaking to the Post about an exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of Art that featured jade animals.

By then, Hotung had gone from knowing nothing about Chinese jade to being a connoisseur – his affinity for jade had become so steadfast that he even carried a handling jade in his pocket.

He would go on to collect more than 300 jade pieces, which were catalogued in a book titled Chinese Jade: From the Neolithic to the Qing (1995), by Jessica Rawson.

“I regard them all like pets,” he said of his jade collection. “I would be upset if anything happened to any of them.”

For two decades following his San Francisco jade acquisition, Hotung did not actively build collections of other kinds of Chinese artworks.

It was only in 1994, after coming across a certain vase at a Sotheby’s sale, that he began to amass a stunning portfolio of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain from the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) and the early years of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

The vase in question depicted the story of strategist Zhuge Liang – a man who rejected the trappings of power by refusing to work for China’s local elites – and it reminded Hotung of the Chinese tales he learned while in Tianjin.

In a letter, Ellen says he wrote that the vase “evoked memories of my youth when I was mesmerised by tales of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which inspired me with stories of valour, honour and loyalty. The purchase of this piece led to an interest in Yuan dynasty wares. I was struck by the power and strength of the pieces, and this led to the formation of the collection.”

In deciding to bid for the vase, he had consulted Regina Krahl, a Sotheby’s consultant and an expert in blue-and-white porcelain (white porcelain decorated with underglaze cobalt).

Over the years, Hotung developed long-standing relationships with art dealers and professionals, many of whom became personal friends and advised him on his purchases.

“He would look for the person or the people that were the best in the field,” says Howard-Sneyd. “He would talk to them, listen to their advice and distil what they had to say, but he would always make up his own mind.”

As a collector, he approached his purchases methodically, buying a few pieces of a particular type first before committing to building a collection over time, as Howard-Sneyd observed.

Hotung balanced his visceral response and personal aesthetic – which Howard-Sneyd describes as that of a scholarly Chinese gentleman crossed with that of a British noble – with the intellectual nature of collecting when deciding to buy certain pieces.

Hotung always wanted to know the full story and history behind a work of art, and also made an effort to record comments and observations of visiting scholars.

“He would never buy an object that he didn’t examine personally,” says Ellen. “He did not believe in buying something online. It was his number one rule when it came to collecting and he would stress it repeatedly.

A piece had to strike a chord with him, and if it did, then he did his best to acquire it. Some people just have an eye for recognising quality artwork and they also can spot a fake. My father was capable of both.”

In his transactions, Ellen says, Hotung adopted a straightforward approach that led to him often being offered first choice in major auctions and with dealers.

“Just as in business, my father was known for his fairness and integrity,” she says.

“When a dealer gave him a price, my father did not negotiate. If he thought it was fair, he bought the artwork, and if not, he would pass on it.”

A book by Krahl titled Early Chinese Blue-and-White Porcelain: The Mingzhitang Collection of Sir Joseph Hotung was published in September this year, detailing his favourite pieces.

“Nobody knows that he has this great collection of blue-and-white porcelain,” says Howard-Sneyd. “When the British Museum reveals it, it will be quite exciting to people in the field.”

While most of Hotung’s jade and blue-and-white porcelain collections will be donated to the British Museum, other pieces in his private collection – many of which were housed in Hotung’s private residences in Hong Kong and London, where he moved permanently in 1997 – have been or are yet to be auctioned through Sotheby’s.

“He created for himself in his home an absolutely extraordinary world,” says Howard-Sneyd.

In his London home, Hotung elegantly paired 18th century British mahogany and walnut furniture with Ming dynasty pieces, which were adorned with beautiful patina and patterning.

Ellen describes this interplay of Chinese and British furniture as “incredible”, noting that the way her father brought them together in one space is a rarity.

His collection of Chinese furniture consisted mostly of pieces made from huanghuali, the chosen wood of the scholarly class during the Ming dynasty and a collector’s favourite.

“[It is] obviously different woods, but there’s a sort of symbiosis between them,” says Howard-Sneyd. “They echo very beautifully across the space of a room together.”

A huanghuali folding horseshoe-back armchair from Hotung’s collection was a highlight at the Sotheby’s sale in Hong Kong, receiving more than 60 bids, and selling for over HK$124.6 million, setting the world auction record and almost doubling the previous auction record for a huanghuali folding armchair.

Other than Chinese art, Impressionist paintings by European artists also made their way into Hotung’s homes.

Ellen remembers a Frans Hals painting, which will be up for auction in London, that was previously positioned in “a place of honour” in Hotung’s home library in Hong Kong, where family and guests would often congregate for a glass of wine in the evenings.

“The subject in the painting has such an affable nature depicted in his expression and repose,” says Ellen of the moustached man depicted, who is seen dressed in black with a white collar. “It was as though he was a family friend participating in the evening’s conversation.”

For Hotung, art served as a backdrop to his life, displayed in all its glory – none of the pieces now up for auction were hidden away in a basement or attic. But this type of display also meant that only those with a keen eye understood their value – that is, if you were privileged enough to be invited into his home.

“You’d almost be ambushed by the object. You’d go in, you’d be offered a cup of tea, you’d sit down on his sofa, and suddenly there in front of you, you would realise was one of the most extraordinary jade buffaloes ever carved,” says Howard-Sneyd.

“He didn’t ever point things out to you. He left it to you to take what you took away from seeing what you saw.”

Though she always recognised her father’s refined taste, it wasn’t until Ellen began visiting museums and studying art in school that she realised many of the artworks she lived with were by world-renowned artists.

“Our home was very different from most people’s, [but] I never felt as though I was living in a museum,” she says. “Having said that, my brothers may have felt differently. Horseplay was not encouraged in the house and balls were strictly forbidden!”

Hotung became involved with the British Museum in the early 90s, after he agreed to finance the replacement of old lighting structures with modern fixtures in the China and South Asia gallery.

But after realising that the installation of new lighting cables required an entire renovation of the gallery, he donated a total of £2 million for the refurbishment. The gallery was reopened by Queen Elizabeth in 1992, and Hotung was named a trustee of the museum in 1994. He would go on to finance a second renovation of the same gallery, reopened again by Queen Elizabeth in 2017.

In Hong Kong, Hotung was the first chairman of the Hong Kong Arts Development Council and donated HK$100 million to the Hong Kong Academy for Gifted Education.

Elsewhere, he became a trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Freer Gallery of Art, in Washington DC, among other establishments. To him, art was the universal language of education, one that was able to cut across “the boundaries of language, culture, history and ethnicity”, says Ellen.

“We were taught by my father that art did not belong to any one person, rather we are stewards, and our role is to ensure that the objects in our possession live on for the next generation and beyond,” she says.

“My father felt that having great Chinese art on display in the British Museum would encourage people to travel to Hong Kong and China, and around the world to see where the art was created. It was his hope that they would meet people different from themselves and explore their cultures.”