Malay and Malaysian: why Hongkongers need to learn the difference

- With a rising number of Hongkongers inquiring about the Malaysia My Second Home scheme, the first step would be to get their facts straight about the multicultural country

I visited Malaysia recently, a country I have great affection for, given its geographical proximity and cultural affinity to my own, Singapore. An increasing number of Hongkongers are inquiring about the Malaysia My Second Home scheme, which allows foreigners to reside in the country. This is not so much a lifestyle choice as one they feel compelled to make because they don’t see any future for themselves in Hong Kong.

Many Hongkongers view the Southeast Asian country with uncalled-for condescension. Perhaps they would do well to learn more about the place. They could start by learning the difference between “Malay” and “Malaysian”.

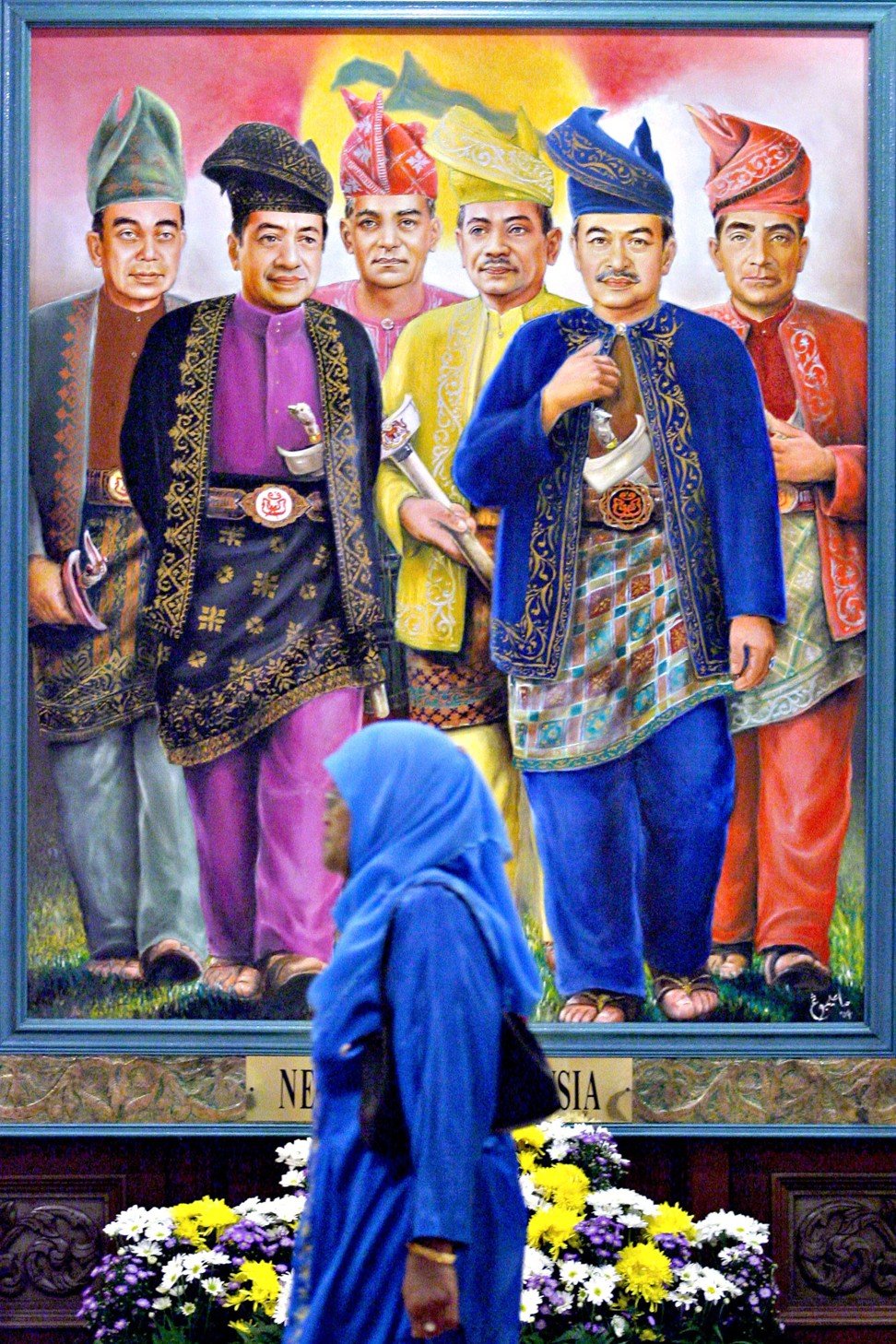

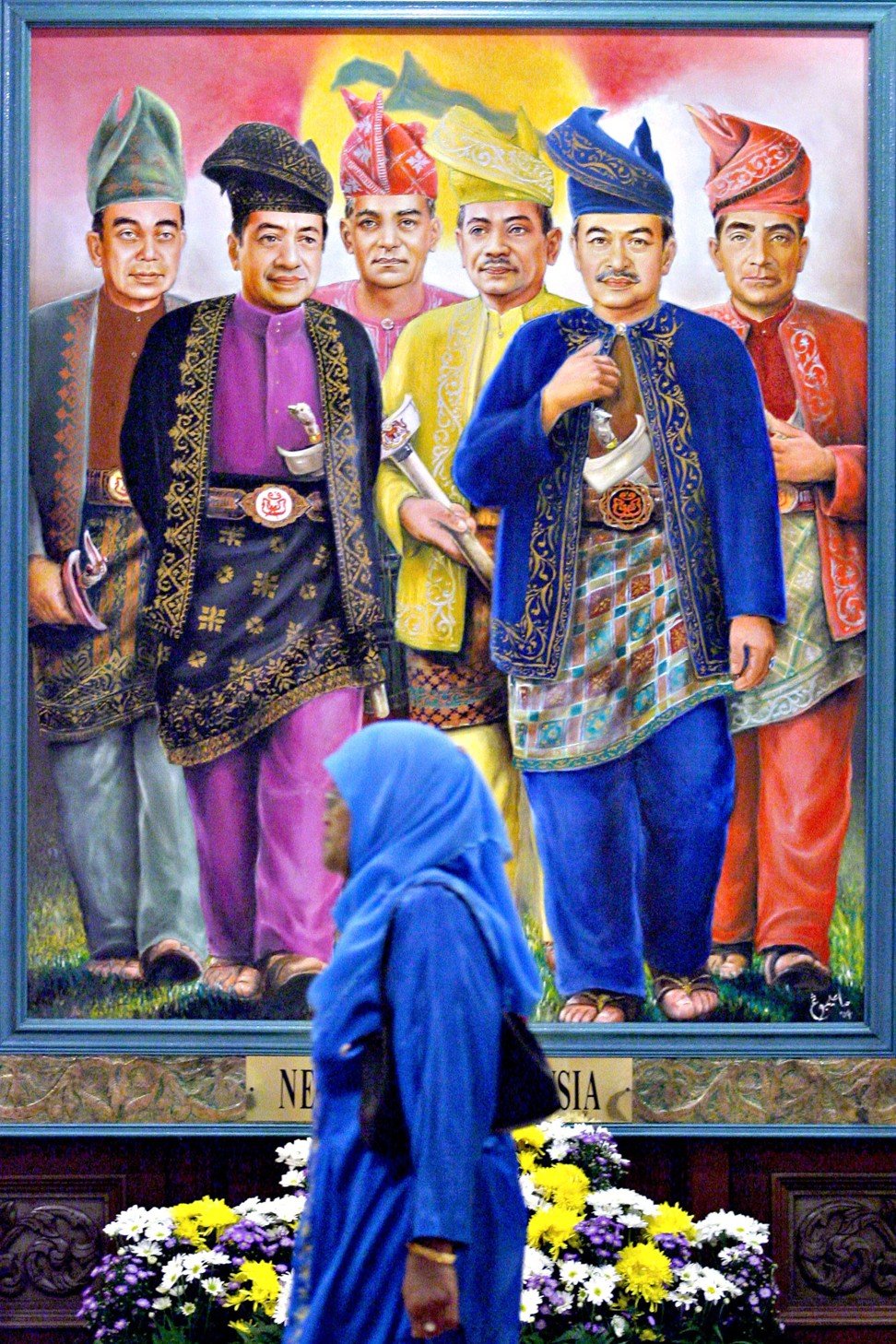

A Malay is a person who belongs to an ethnolinguistic group found across Southeast Asia, from Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, to parts of Cambodia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, even as far afield as Australia’s Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Sri Lanka and South Africa. A Malaysian, however, is a citizen of Malaysia. He or she could be of Malay, Chinese or Indian heritage, or any one of the many ethnic groups that make up the multicultural country.

One of my pet peeves is many Hongkongers’ conflation of “Malay” and “Malaysian”. For instance, when they speak of “Malaysian food” when they are really talking about Malay cuisine, or when they refer to the country in Cantonese as Ma Laai (“Malay”).

The full Mandarin Chinese name of the country is ma lai xi ya, a phonetic rendition of “Malaysia”, but many media publications, for the sake of brevity, shorten the four-character name to ma guo (“the Ma country”) or da ma, where da means “great” or “big”. It is also common among some older Chinese Singaporeans to refer to Malaysia as lianbang (“the federation”), a fading echo of Singapore’s short-lived membership within the Malaysian federation more than half a century ago.

There are records of what is present-day Malaysia in ancient Chinese texts and maps composed by Chinese travellers. The sultanate of Melaka, in the present-day Malaysian state of the same name, was one of the first kingdoms on the Malay Peninsula to establish formal ties with China, in the 15th century. Typical of the Chinese empire’s view of itself as the centre of the world order, it was an unequal relationship, with Melaka pledging fealty and paying tributes. Due to China’s status as Melaka’s protector, the Portuguese conquest of Melaka in the early 16th century had a negative impact on China’s relationship with the first Europeans in Asia in the modern era.

Over the centuries, many Chinese arrived and settled in the Malay Peninsula. Encouraged by the British colonial administrators to augment the local labour force, Chinese immigration to the territory spiked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Most of their descendants are the Chinese Malaysians of today, who account for about one-fifth of the country’s population.

Contrary to the expectations of many in China, Chinese Malaysians, like ethnic Chinese communities in Singapore and other parts of Southeast Asia, identify more with their home countries than the distant home of their ancestors. Our relationship to China is not unlike how Americans or Australians of Anglo-Saxon descent relate to the British Isles, which is as it should be.