How communication has changed, from Pompeii graffiti to personal notes to social media

- With Wi-fi now instantly connecting the planet, we look back at the various ways mankind has sought to converse

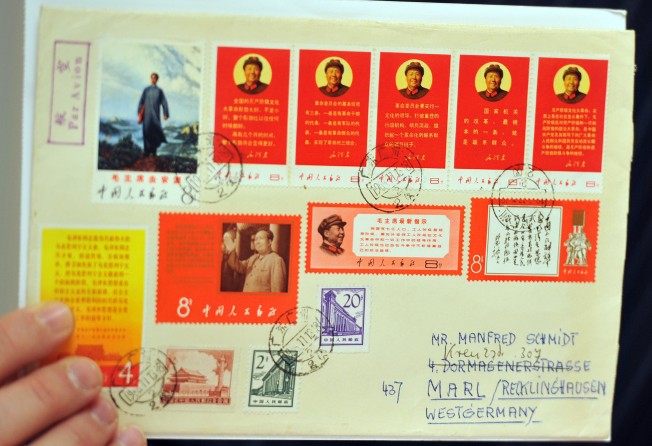

- In the 1920s, airmail services shrunk the sending time for written correspondence to days, rather than weeks

Around the world, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram and other social media have replaced more traditional forms of communication that involve real-world (as distinct from virtual) friendships. A sign, recently spotted in a cafe at a popular tourist spot in Vietnam, summed it up: “Hungry? We have food. Thirsty? We have drinks. Lonely? We have Wi-fi.” The old-fashioned idea that a cafe might be a place to meet and chat with other people has left the equation.

And, of course, once the online equivalent of a belch has been uttered, both echo and stench live on for evermore in cyberspace. Once out there, these personal clues remain subject to multiple levels of official and commercial collection, surveillance and interpretation that an earlier generation would have found inconceivable.

As Wi-fi connections spread all over the world, instant electronic communication is taken for granted. Stories of children looking at a typewriter and asking where the screen is, or handling an analogue telephone as though it was some incomprehensible Stone Age artefact, are common.

But crabby-sounding Luddite tendencies to one side – and I’ll admit to those, when it comes to social media – how did one keep in touch in the past, especially with friends and business connections on the other side of the world? And how do these earlier forms of communication echo in how we live today?

Personal notes were the usual means of communication, and those that have somehow survived, tucked away in bundles of correspondence, offer intriguing insights into everyday lives in earlier times. Much like graffiti entombed on the walls of Pompeii, in southern Italy, when Vesuvius erupted in AD79, which contains the first century equivalent of “Mandy is a skank” or “For a Good Time Ring …”, snippets of gossipy ephemera serve to remind us that human beings have remained basically the same in the most fundamental respects for millennia.

Notes were also sent with servants. In one of her Hong Kong reminiscences, British author Stella Benson, librarian at the Helena May for a while in the 1920s, tartly described how a note would be sent down from a member, telling her to send back two books with the bearer; just what kind of book they might like to read was left for her to decide.

Written communications rapidly changed when the Suez Canal opened in 1869. Following that, mail took about six weeks to reach destinations across the Far East from Europe. Before that, overland mail, which went by pack horse over the Sinai desert between Port Said and Port Suez, took a little longer, while most letters spent about four months in transit during the voyage around Africa via Cape Town.

Airmail services from Europe to parts of Asia and Australia started only in the 1920s, were expensive and still took well over a week. Much like analogue telephones and typewriters, airmail paper and envelopes or – even more unusual – single-sheet aerogrammes that can be folded up and sealed down, seem impossibly antique to the current generation accustomed to global social media and email connections.

The Biblical quotation, taken from the Book of Proverbs, inscribed on Hong Kong’s General Post Office – “As cold water to a thirsty soul, so is good news from a far country” – was moved from the old General Post Office, at the junction of Pedder Street and Des Voeux Road Central, when that building was demolished in 1976. The teak plaque can still be seen at the top of the escalators in the replacement building. Hopefully an appropriate new home can be found for this local history fragment when that building is eventually redeveloped.