Beyond treason: Hongkongers who collaborated with the occupying Japanese

- The reasons for working with the invading force were myriad but the main attraction, as always, was money

- While the wealthy and well-connected avoided prosecution, those lower down the social scale were often arrested and tried

Collaboration with an enemy occupation happens for complex reasons. Economic advantage; political ideology; long-smouldering personal vendettas and jealousies; socio-economic or racial grievances; a repressed desire for revenge on those who once had power, and used it to the disadvantage of those now seeking vengeance – all of these factors can coalesce to create the Quisling type.

Hong Kong, from its mid-19th century urban beginnings, was the kind of society that encouraged collaborators; the most successful Chinese businessmen were those prepared to shamelessly operate under a foreign flag for their own benefit. Personal motivations – however much their descendants may wish to rewrite family pathways to prosperity – were basic. Financial gain and the Devil take the hindmost summed these people up.

In any filthy body of water, scum rapidly rises to the surface when stirred up, and so it has always been in Hong Kong. It was much the same a century later, during the Japanese occupation period.

In The Hidden Years: Hong Kong 1941-1945 (1967), author John Luff noted, “There were those who valued their skins, whatever their colour, above patriotism and decency. These people did not turn on their countrymen but merely turned their coats.” Others, motivated by a complex web of simmering personal grudges, deep-seated racial animosities, a sadistic enjoyment of power – especially over the weak and vulnerable – and the ever-present inducement of easy financial gain, made good wartime stooges.

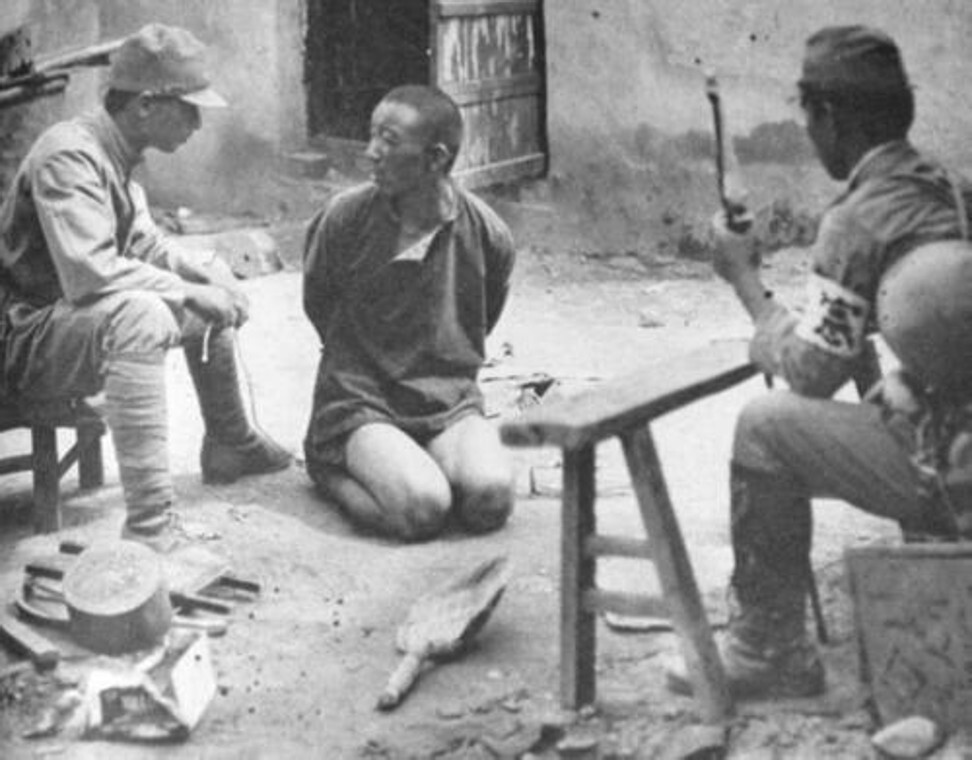

Among the vilest collaborators was George Wong. For the pre-war manager of a Kowloon motor garage, financial inducement was a key factor. He became a driver for the Koa Kikan – the Japanese secret intelligence service – then a paid Chinese agent/informer, and eventually evolved into the chief local thug for the Kempeitai, the Gestapo-trained Japanese secret police.

Another ghastly figure was Howard Tore, proprietor of the Capitol Ballroom in West Point, just below the University of Hong Kong, where he was known – pre-war – for greeting all comers to his establishment with a hearty “Call me Howard!” According to various sources, Tore’s visceral dislike of Europeans – masked by a permanently grinning, obsequious manner – evolved from racial slights endured as a child in England.

Both men routinely operated independently of their ostensible paymasters, frequently rounding up their own targets and extorting money or sex from their victims in return for keeping them or their family members out of Kempeitai hands. Fear of arrest was enough to make even the innocent do whatever these men demanded.

Senior community figures in Hong Kong neatly avoided prosecution for collaboration; as ever, one set of standards applied for the wealthy and well-connected, and another for everyone else. As is often the case with that section of society, inconvenient truths were brushed under the carpet.

In addition, the colony’s post-war toy-town political engine needed its pre-war batteries to help power it along, however stale they may have been. It was in no broader interest to go after people from whom nothing better could have been expected in the first place.

Those further down the socio-economic scale – like Wong – who had actively assisted the Japanese secret police, were another matter altogether. “So bitter was the liberated population of Hong Kong with these turncoats,” Luff noted, “that they demanded their arrest and trial.”

Wong went to ground after the Japanese surrender, in August 1945, but foolishly remained in Hong Kong; Tore – sensibly – escaped to the mainland. Eventually, Wong was discovered by the police, hiding beneath a woodpile in a Kowloon garage in April 1946. Subsequently tried, and found guilty of 36 counts of treason, he was hanged in Stanley Prison on July 10, 1946.