The Chinese history book that got 70 people executed, 14 very slowly via ‘death by a thousand cuts’

- In perhaps the most famous example of ‘literary inquisition’ in Chinese history, more than 1,000 people were punished for the publication of a Qing-era book

- Members of the author’s family, the editors, bookshop proprietors and buyers were all executed. The deceased author’s remains were exhumed and desecrated

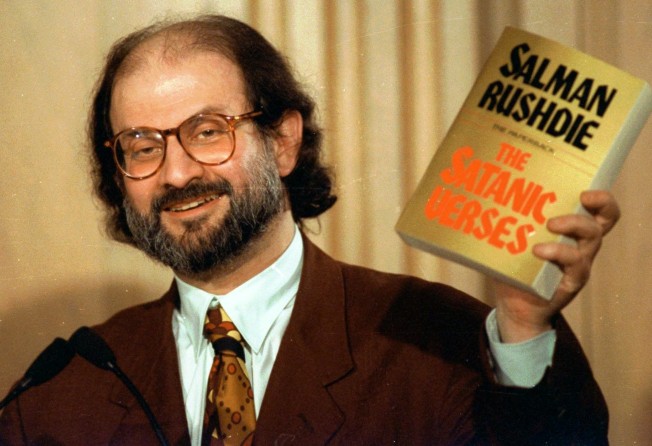

On August 12, India-born British-American writer Salman Rushdie was seriously injured after he was stabbed multiple times at a literary event in the United States as he was about to give a talk on artistic freedom.

It’s a topic with which he is familiar: Rushdie’s controversial novel The Satanic Verses (1988), which many Muslims consider blasphemous, incurred the wrath of Iran’s late leader Ayatollah Khomeini, who issued a fatwa in 1989 calling for the writer’s death. The decree remains in force today and might have been responsible for the attack.

Many had suffered for the written word in China’s past. Wenzi yu, or literary inquisition, was an effective weapon wielded by the state to persecute writers and other members of the intelligentsia for perceived threats to imperial authority.

The Qing dynasty (1644-1912) was notorious for the heavy human toll of its literary inquisitions, the most famous of which was the one that involved the book Introduction to the History of the Ming.

It all began around 1650, when a wealthy man, Zhuang Tinglong, wanted to bequeath a legacy in the form of a historical monograph bearing his name.

Not being an especially erudite man, he bought a manuscript of an account of the preceding Ming period (1368-1644), written by a deceased official of the recently fallen dynasty, and then engaged dozens of literary men to edit the manuscript and write a preface for the book that would bear his name.

Introduction to the History of the Ming was finally published in 1660, five years after Zhuang’s death. It was immediately apparent that the book was “problematic”.

Ming-era reign period names were used instead of those of the Qing, suggesting that the writer and editors were Ming loyalists who regarded the Qing rulers as illegitimate usurpers.

Even worse, the book was peppered with pejorative epithets like “barbarians” and “savages” in reference to the Manchus, the very people who had recently occupied China and as conquerors, formed the current ruling elite.

It is possible that Zhuang’s editorial team had intentionally left these in. The Ming had fallen less than 20 years prior (a loyalist regime was still ensconced on the island of Taiwan at that time), and most of the Han Chinese intelligentsia resented their subjugation by a foreign people whom they considered culturally inferior.

The following year, a Han Chinese district magistrate reported the subversive publication to the imperial court. The reprisals were swift and terrible.

Several members of the Zhuang family, the editors, the scholars who had co-written the preface, and even the printers involved in the production process, proprietors of bookshops that stocked the books, and individuals who bought them – they were all executed.

Dozens of local officials were charged with negligence for allowing such a heinous publication to see the light of day and were executed, demoted or dismissed. Family members and associates of the guilty men were exiled to the furthest reaches of the empire as labourers or slaves.

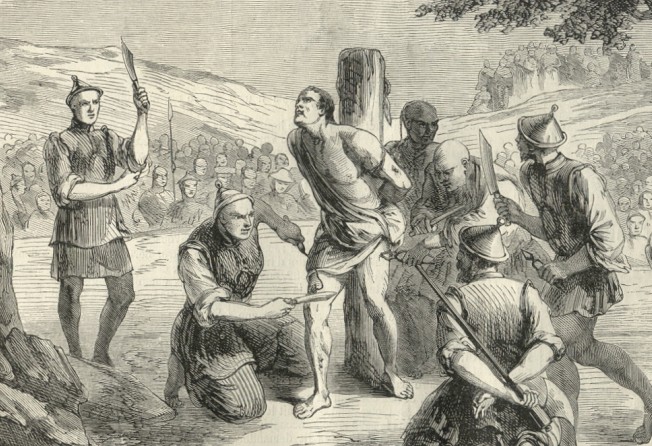

In total, more than 1,000 people were implicated and punished. More than 70 people were put to death, 14 of whom suffered excruciating deaths by lingchi, also known as death by a thousand cuts.

What of Zhuang Tinglong, the affluent dilettante who started it all? His remains were exhumed from his grave and desecrated.

Like all witch hunts, this and other similar literary inquisitions were marked by arbitrariness and gross injustice, aggravated by plaintiffs and informants waging personal vendettas against their enemies.

The intention of these highly public and often violent persecutions was to intimidate and warn the population, in particular the intellectuals. In almost all cases, the goal was met.