At a Native American pow-wow in Wisconsin – once oppressed people finding their place in modern US

- The Ho-Chunk tribe’s ritual gathering is a deeply spiritual event in the heart of ‘America’s Dairyland’ – and definitely not for the benefit of tourists

How should you respond when a striking Native American woman asks you to attend her pow-wow?

Leah Ann Walker invited me to the ritual gathering of her tribe, the Ho-Chunk, during the Venice Biennale of Art, where avant-garde Native American artists present an alternative pavilion to the official United States one. Her offer of what sounded like a genuine adventure was one I could not refuse.

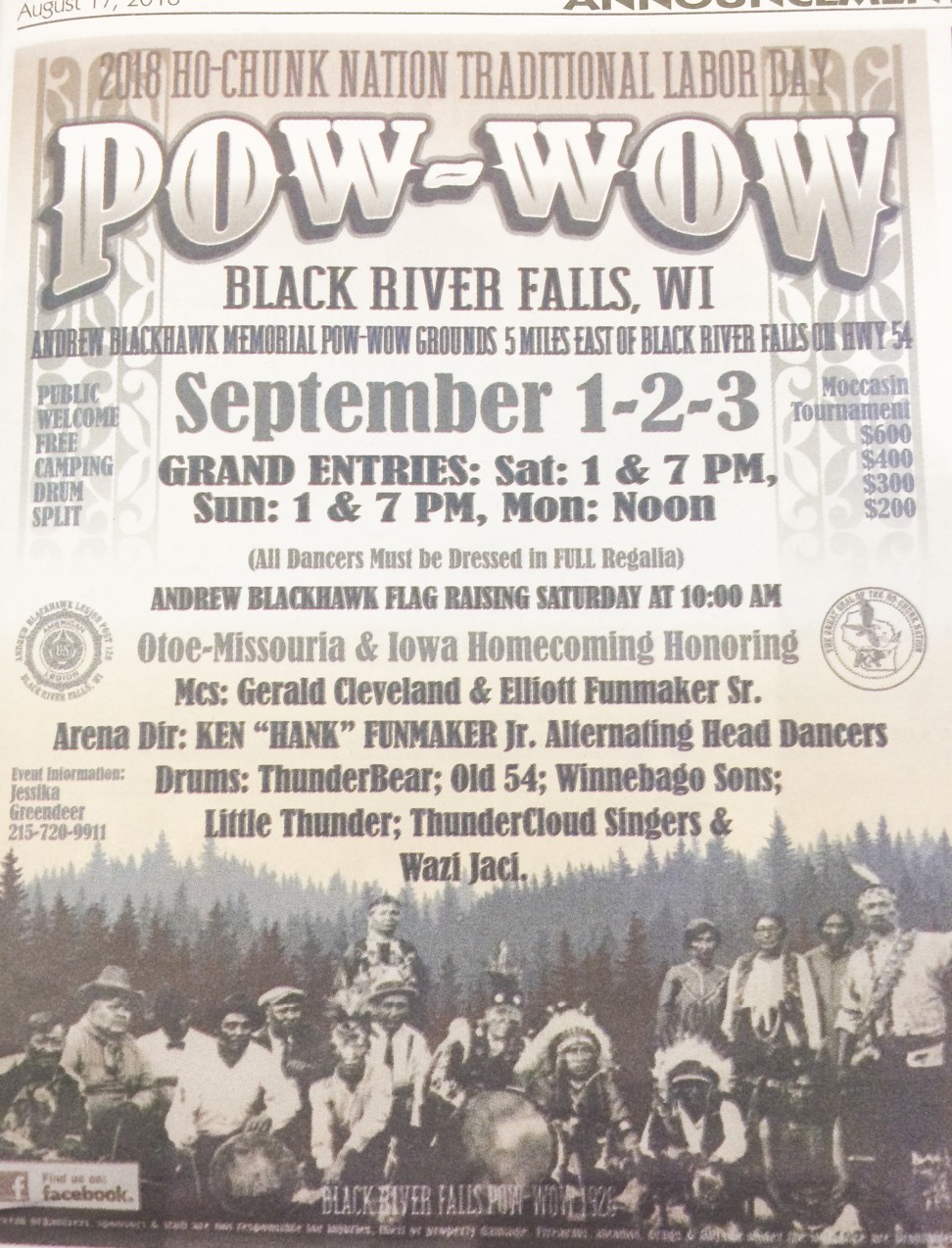

Six months later, and I am driving out of Chicago towards Black River Falls, in the wilds of Wisconsin, not quite knowing what to expect from the three-day gathering. Non-stop traditional dance and music, as well as splendid ceremonial robes, are a given, but perhaps it’ll also be a spiritual experience or an opportunity to blow away movie-inspired preconceptions and observe the reality of a people who have been oppressed for centuries but are finally finding a place for themselves in modern America, where public statues of brave colonial settlers conquering merciless savages still stand.

Apart from advising me to respectfully call my Ho-Chunk hosts Native Americans – “never, ever, call anyone a Red Indian” – Walker has given me list of dos and don’ts: tribe members in the pow-wow will be dressed in traditional “regalia”, not “costumes”; don’t touch anyone or even think of asking them to pose for a selfie; don’t ask about Thanksgiving as, “we don’t actually celebrate that”; and no mention of a certain Christopher Columbus – “where, exactly, is he meant to have discovered?”

And crushing my Hollywood-inspired illusions, there will be no peace pipe to puff on nor any mind-bending peyote: the three-day event is a detox, with all booze and drugs strictly prohibited.

Black River Falls is a small logging town surrounded by thick woods, picturesque lakes and bucolic red wooden farm buildings; its cows and cheese have earned Wisconsin the title “America’s Dairyland”. This is the ancient homeland of the Ho-Chunk, a warrior tribe related to the Sioux whose bloody history saw them uprooted and forcibly moved to South Dakota and Nebraska before finally returning around 50 years ago, to reclaim their turf from the government. The Ho-Chunk do not live on a reservation and about 3,000 of them call Black River Falls home.

It looks as though most of them are gathered at the Memorial Pow Wow Grounds, an outdoor arena encircling a green field that is already packed with flamboyantly dressed dancers, singers and musicians. At 11am, I take my seat on the bleachers just as the Grand Entry begins.

The formal procession soon devolves into a mesmerising dance, as pulsating drum beats and bewitching chants create a trance-like atmosphere, the participants becoming lost in their own world, swirling on a personal warpath in silent tribute to fallen ancestors.

Participating is an intensely personal experience and a sacred duty of a people [...] desperate to reclaim and celebrate their identity, heritage and language

Each dancer’s spectacular regalia has been painstakingly handmade by the participant and his family. Magnificent war bonnets are fashioned out of multicoloured eagle and wild turkey feathers; tall porcupine needles shoot up from one headdress; rows of bison teeth form a chest plate; jackets, breeches and dresses have been meticulously embroidered with precious stones, beads, animal hides and shells. Some participants brandish warlike cudgels, spears and shields, and moccasins are decorated with bells, their jangles adding to the music.

Each dance lasts for between 15 and 20 minutes, ending in a prayer, with just a short break before the next begins, and this cycle continues for some eight hours, until twilight. No one looks a bit tired, although the intensity has left me exhausted, even overwhelmed, because the pow-wow is clearly not performed for the benefit of tourists. Participating is an intensely personal experience and a sacred duty of a people – from octogenarians proudly walking the parade to exuberant young dancers, and even tiny tots trying to take the proceedings seriously – desperate to reclaim and celebrate their identity, heritage and language.

The next day I take a break from the rituals to explore Black River Falls and its surroundings.

Top attraction on sleepy Main Street is the Cozy Corner, a saloon run by the daughter of tribal chief Clayton Winneshiek. She makes a memorable Bloody Mary, with a typical Wisconsin garnish: gherkin, olive, pepperoni, ham and cheese. Boutique-beer types gather around the corner, at the Sand Creek Brewing Company, founded by 19th-century Swiss immigrants, to sup on a velvety porter, American brown ale and hoppy IPA.

The town is surrounded by lakes and wetlands, and a 10-minute drive away is Lake Arbutus. The water is encircled by tall pine trees sheltering a huge campsite filled with tents, caravans and gigantic camper vans. When I arrive, a mammoth weekend flea market is being set up, an eclectic slice of rural America where you can buy a redneck door sign reading, “Trespassers will be shot. Survivors will be shot again”, delicious organic cheeses and home-made jams, kitsch Americana souvenirs and even designer furniture made by the distinctive long-bearded Amish people, who still get around by horse and carriage and live without electricity.

The Stone’s Throw, a stone’s throw from the flea market and at the water’s edge, is one of the few remaining Wisconsin supper clubs, which are found in rural settings, standing amid forest or beside a lake, and continue a tradition of dining and drinking that dates back to the days of Prohibition. Supper clubs start serving dinner as early as 4pm, with last orders at 9pm.

A red wooden cabin filled with cosy leather banquettes and booths, its walls adorned with stuffed fish and bear and moose heads, and dominated by a U-shaped bar lined with tall stools, the Stone’s Throw is as much social club as restaurant, with patrons lingering over the salad bar, signature giant steaks and a steady supply of brandy-based Old Fashioned cocktails as they discuss the exploits of local football team the Green Bay Packers.

The pow-wow seems a world away, and although we are welcomed by the locals – they don’t get many foreign visitors in these parts, some want to buy my euros as souvenirs – it seems wise to steer the conversation well clear of politics.

I spend the last morning of the pow-wow enthralled again by the rhythmic dancing before one of my new friends, Nehomah Thundercloud, an educational programme director, takes me and Walker on a more edifying tour of Black River Falls – which begins at the casino.

The Ho-Chunk are one of many tribes that have taken advantage of the fact their ancestral lands lie beyond federal jurisdiction and set up Las Vegas-style casinos. The profits from Ho-Chunk Gaming – along with hard-won federal grants – have been invested in a host of social-welfare projects for the tribe; a medical and dental centre; arts-and-crafts programmes; a retirement home; an independent law court; and schools that concentrate on teaching the Ho-Chunk language, which, for long periods, the people were not allowed to speak.

The Ho-Chunk are one of hundreds of Native American tribes, most of which hold regular pow-wows that are open to all, offering an opportunity to gain a unique view of a pre-Columbian world.

Getting there

Cathay Pacific and United fly direct from Hong Kong to Chicago.