Silent Night: Austrian city of Salzburg pays homage to 200-year-old carol that put first world war on pause

- It is the quintessential Christmas carol and this year, Salzburg and a nearby village that is its birthplace celebrate the 200th anniversary of its first performance

- When Joseph Mohr put pen to paper to write the lyrics, the world was emerging from dark days – quite literally – and his hymn was a message of hope

It’s early December, and I’m standing in Salzburg’s snow-dusted Residenzplatz, sipping mulled beer (yes, you read that correctly, and it’s actually rather good) and listening to trumpeters perform Silent Night. This year marks the 200th anniversary of the carol’s first public performance, on Christmas Eve, 1818, at a tiny church in the nearby village of Oberndorf.

It’s an anniversary the Austrian city is celebrating with gusto. Joseph Mohr, who wrote the lyrics, was baptised inside Salzburg Cathedral, later becoming a priest in Oberndorf, where Franz Xaver Gruber, who wrote the music score, was an organist.

At the Silent Night 200 exhibition, which runs until early February at the city-centre Salzburg Museum, visitors can learn how to “sing” the carol in sign language, and how to say its first lines in some of the 300 languages it has been translated into (“busuku obuhle” is Zulu for “silent night”). A popular exhibit is a hi-tech display of QR code-adorned cards, which can be placed on a panel to reveal weird and wonderful facts: Bing Crosby’s version of the carol sold 30 million records; there wasn’t a single portrait painted of Mohr. In 1912, when artist and priest Josef Mühlbacher was asked to sculpt a monument honouring the carol, Mohr’s body was exhumed to give him an idea of the lyricist’s appearance.

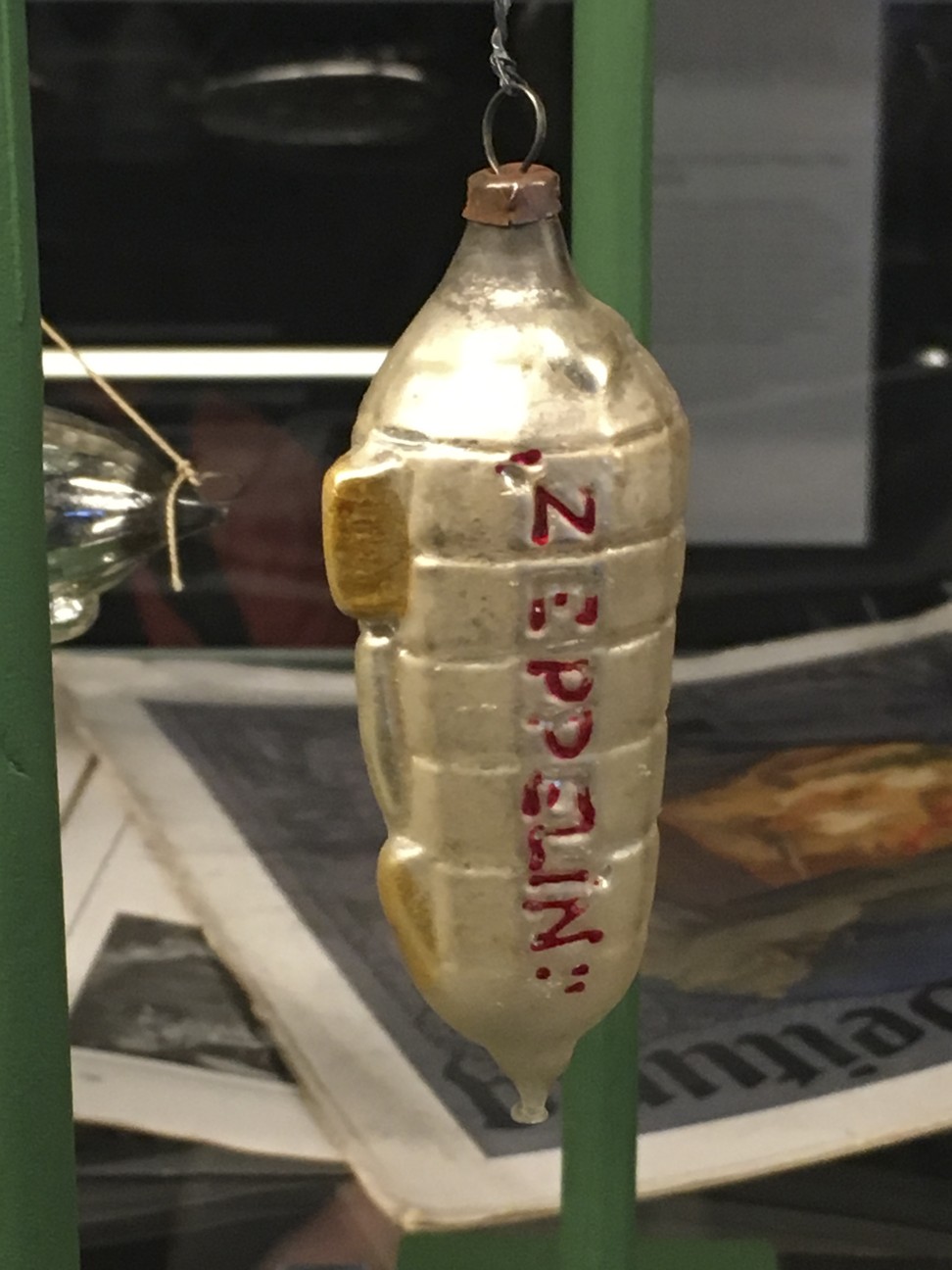

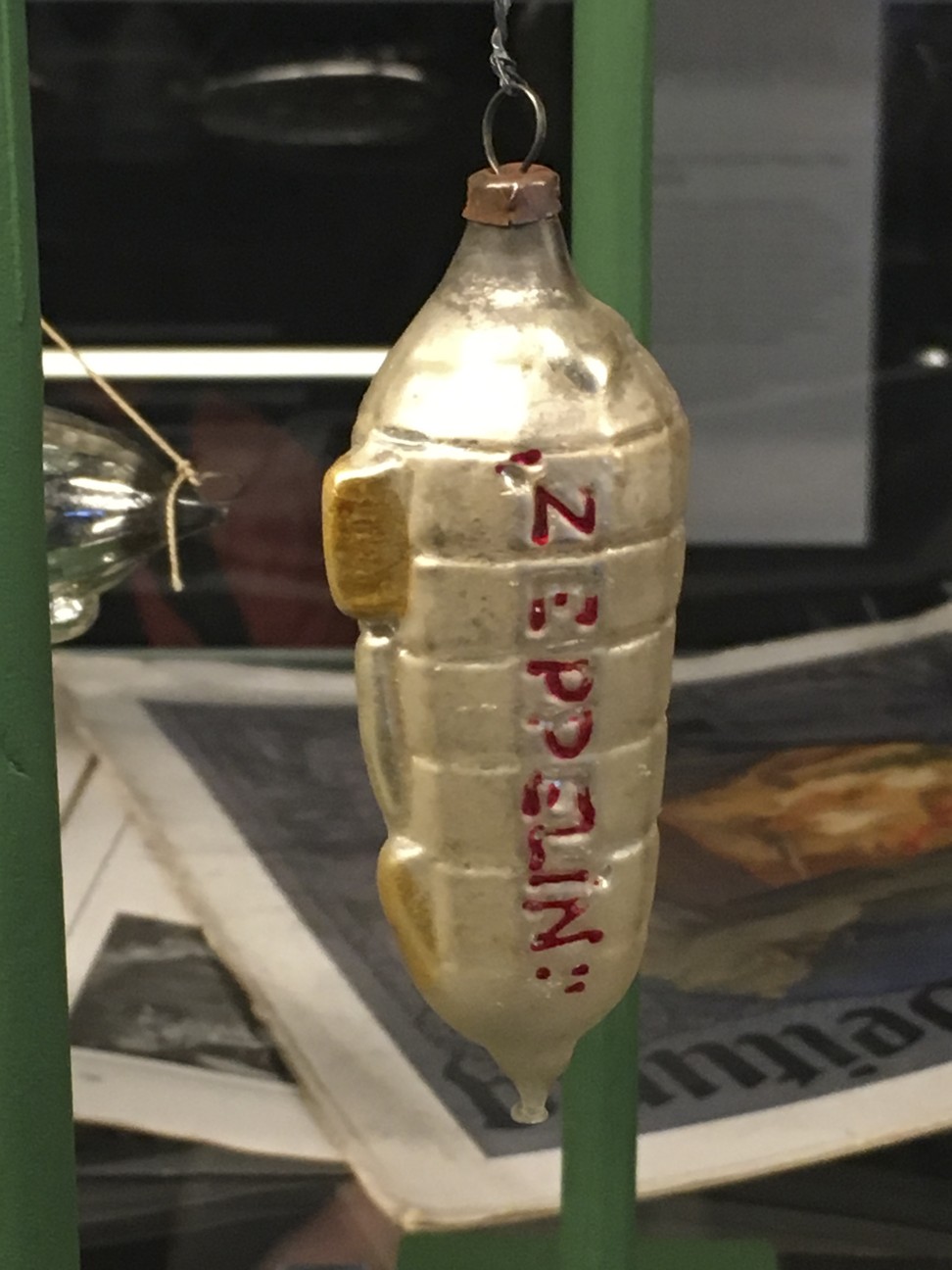

Downstairs is a collection of Silent Night memorabilia. The carol has been used to sell everything from wine and beer to cigarette lighters and thimbles. Also on display are Christmas ornaments dating back to the first world war – miniature silver Zeppelins and hand grenades, which once dangled from trees. They are a nod to the carol’s reputation as the song that put a war on pause.

On Christmas Eve, 1914, German officer Walter Kirchhoff, a tenor with the Berlin Opera, emerged from the trenches and sang Silent Night in German, then in English. British troops joined in, in a brief respite from the horrors of battle.

The kitsch knick-knacks belie Silent Night’s stark origins. In 1818, Europe was licking its wounds after the Napoleonic wars, and much of the world was recovering from the devastating effects of the 1815 eruption of Indonesia’s Mount Tambora. It was heard more than 1,000km away and was the most devastating volcanic event on record. A thick fog of ash drifted from Southeast Asia, blocking out sunlight and prompting historians to dub 1816 the year without summer. In much of North America and Europe, the ground remained frozen in June. Germany and Austria were affected more than most. Crops failed, prompting food shortages, widespread rioting and the worst famine of 19th-century Europe.

When Mohr put pen to paper, the world was emerging from dark days – quite literally – and his hymn was a message of hope.

Outside the tiny Silent Night Chapel in Oberndorf, a crowd is gathering. Luckily my guide, an expert on the carol, has friends in high places, and he shows me inside before the chapel opens to the public. Silent Night was first performed here, but in a different building: St Nicolas Church, which stood on the same site, close to a bend in the River Salzach.

In the 18th century, the boatmen who paddled salt-laden barges along the river loathed this spot – submerged boulders made the bend impassable, forcing them to unload their boats and drag them across a strip of land before re-entering the water. In winter, the situation was bleaker still, and to raise their spirits, bargemen banded together to sing carols, often in return for food given by wealthy merchants. In summer, they prayed to St Nicolas – to whom the original chapel was dedicated – for safe passage down the river.

After St Nicolas Church had fallen into disrepair, the Silent Night Chapel was built to honour the original – and in a nod of respect to the bargemen, and the patron saint who watched over them. Its opening in 1937 was attended by the Austrian chancellor and Gruber’s grandsons – outside the chapel is a picture of them singing Silent Night at the event. Inside, there is room for little more than two rows of three short pews, a guestbook, an altar and two rather severe-looking portraits of Mohr and Gruber. The spartan surroundings remind visitors of the hard times that inspired their famous carol.

Oberndorf’s pastel-pink Stille Nacht (“silent night”) Museum – the former parsonage, which was Mohr’s home between 1817 and 1819 – is metres from the chapel.

His superior, who lived nearby, thought of Mohr as a rebel, and complained about the “un-priestly” behaviour of a man who was partial to pipe-smoking and enjoyed the occasional beer. The protests were ignored, Mohr stayed, and in 1818 he performed Silent Night, a poem he had written two years earlier, with Gruber.

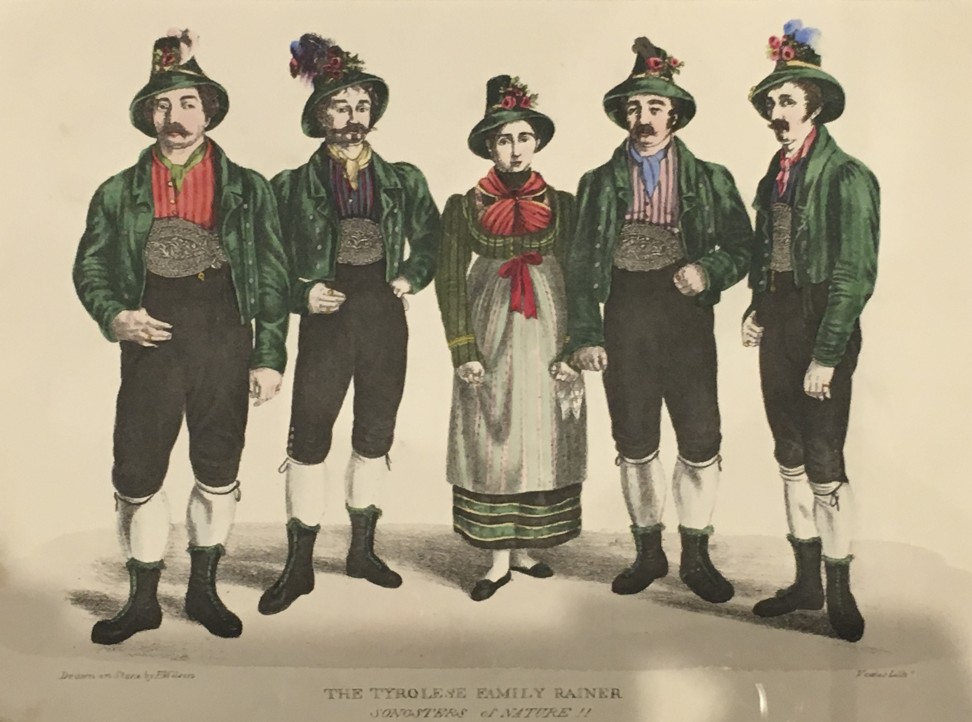

A year later, Carl Mauracher, a Tyrolean organ builder passing through Oberndorf, heard Silent Night and introduced the carol to his hometown of Fügen, about 140km (87 miles) to the southwest. The quaint town happened to be the home of the Rainer family, a travelling troupe of singers who added the song to their repertoire.

When Tsar Alexander I heard the song during a visit to Austria, he invited the troupe to perform for him in Russia, and the Rainers became an overnight success. Soon afterwards, they achieved what many of today’s big European pop acts fail to do – they cracked America, arriving in New York in 1838. The carol was performed there for the first time outside New York City’s Trinity Church. In 1859, it was translated into English and by 1872, it was a staple of American hymnbooks. In 1905, the popular American a cappella group The Haydn Quartet made the first recording. The arrival of radio in the late 1920s allowed it to be heard around the world, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Numerous recordings followed, and in the museum is a karaoke booth where visitors can sing along to versions by Taylor Swift and Die Toten Hosen, a rather shouty German punk band, among others. What Gruber and Mohr would have thought, one can only imagine.

At the rear of Salzburg Cathedral is the enormous font in which Mohr was baptised. He was in good company; Mozart had been baptised there 36 years earlier.

Mohr’s mother had four children by different men. She refused to identify his father but decided Salzburg’s executioner was an acceptable stand-in, naming him godfather. He, though, was too busy to attend the baptism, sending his maid instead.

It was the cathedral’s vicar who encouraged Mohr to study music. He later joined the church, despite the many obstacles in his path to the priesthood. Because of his illegitimacy, special dispensation was required, but in 1815 Mohr was ordained.

The cathedral is just around the corner from Salzburg’s Felsenreitschule theatre where, in November, a new play, My Silent Night, was performed for the first time. Fittingly, for a play based on a song written by one of the 19th century’s most famous composers, the Salzburg State Theatre commissioned one of the 21st century’s most famous composers, John Debney, to write the score. Debney, who composed the Oscar-winning music for 2004 film The Passion of the Christ wasn’t the only big name involved – the lyrics were written by Siedah Garrett, who penned Michael Jackson’s Man in the Mirror.

I suspect this particular tribute is one Mohr and Gruber would have approved of.

Getting there

Lufthansa, KLM and Turkish Airlines offer connecting flights from Hong Kong to Salzburg.