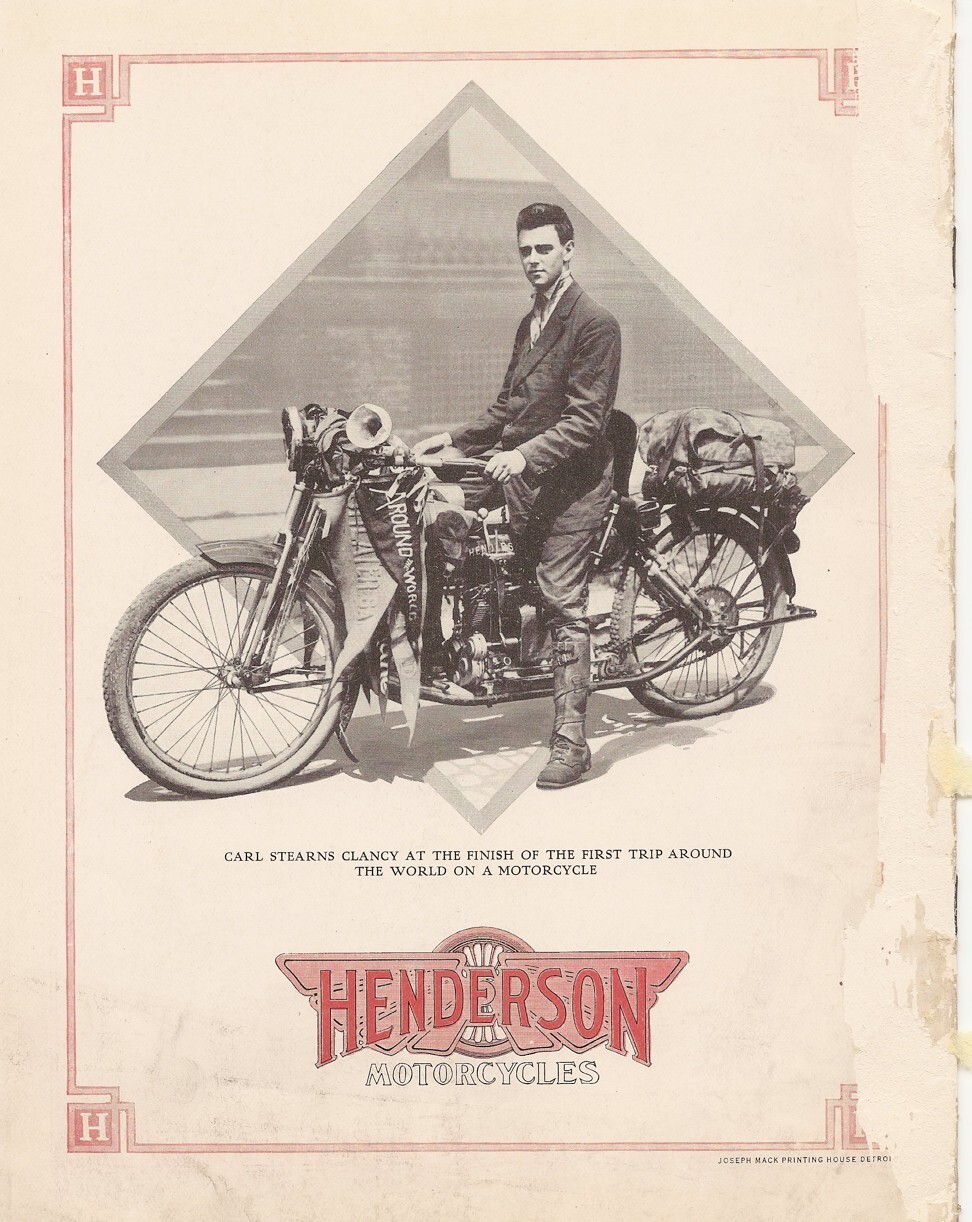

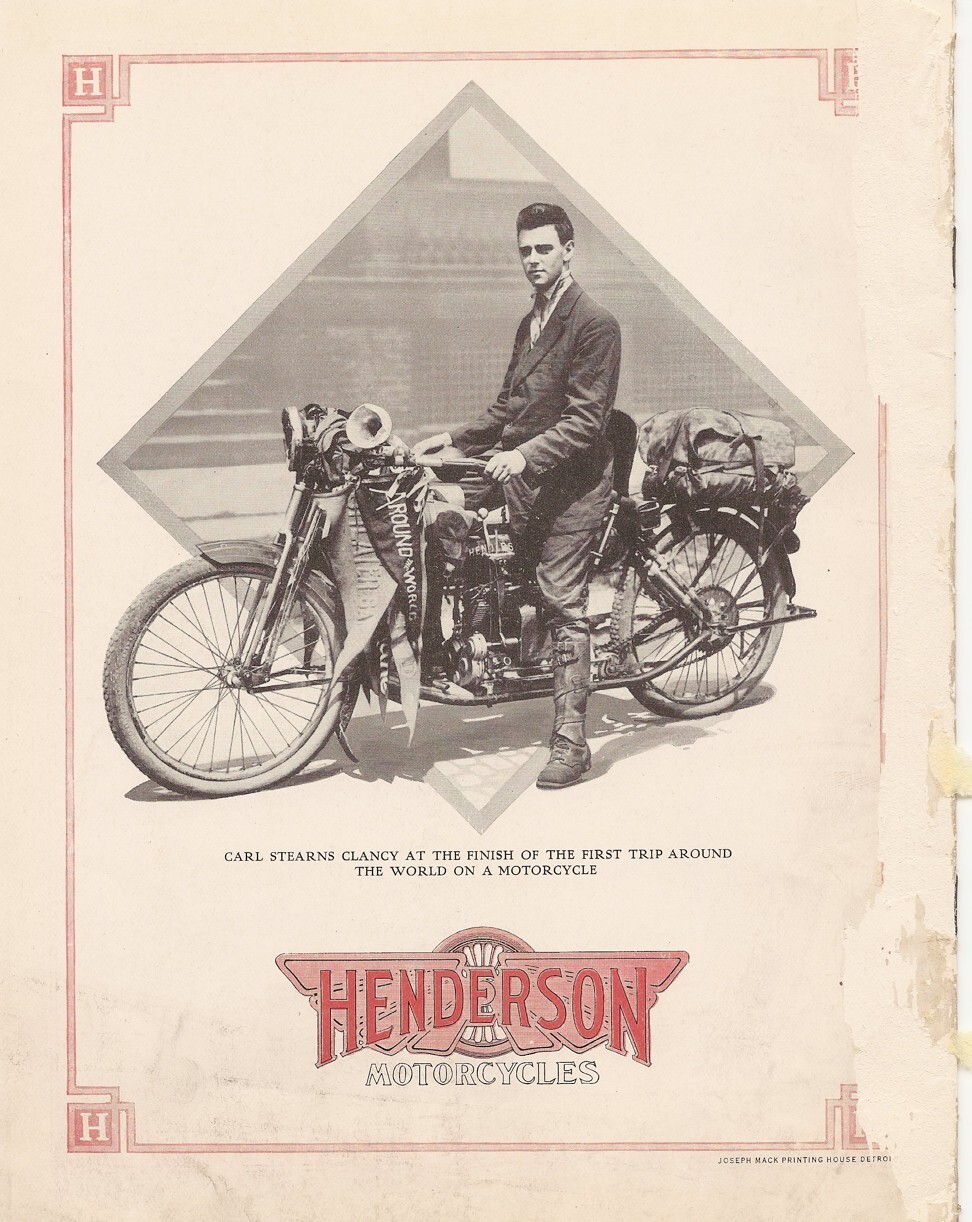

Around-the-world motorcycle touring pioneer Carl Stearns Clancy, and what he thought of Shanghai and Hong Kong in 1913

- Dressed in a three-piece suit and tie, Carl Stearns Clancy circumnavigated the globe on a single-gear motorbike

- He was impressed by the ‘quiet, respectful, courteous and neat’ Chinese he found in Hong Kong

It was going to be the “longest, most difficult, and most perilous motorcycle journey ever attempted”. At least, that was the opinion published by The Bicycling World and Motorcycle Review when it hit American news stands in the autumn of 1912.

The trailblazing odyssey was to take a 20-something advertising copywriter from Epping, New Hampshire, around the planet on a 934cc Henderson Four, which boasted a single gear and no front brake and retailed for US$325. The machine’s devil-may-care pilot was Carl Stearns Clancy, and rain or shine, sweltering tropical heat or nigh Arctic blizzard, he was to be found mounted on his two-wheeled steed wearing a three-piece suit with a collar and tie. Truly, this was the 24-carat golden age of the amateur gentleman adventurer.

In some ways, travel was simpler then. Rather than being straitjacketed by a daily blog and festooned with corporate logos, Clancy was able to fund his trip with occasional journalism. If roads were fewer and patchier, traffic was certainly lighter, although it was rare that the Henderson could hit its top speed of 105km/h.

No prurient documentary camera or local television news station poked its lens into Clancy’s innermost feelings along the way. And if he had forgotten to pack the relevant map – as he did in Ireland, on the first leg of the trip – or there was no map at all, there was usually an admiring soul who was more than willing to help out with directions.

Clancy was also fortunate with his timing: in August 1914, a year after he completed his epic journey, Europe and much of the rest of the world was engulfed in a bitter and bloody war. Freewheeling travel became next to impossible.

“Clancy was every bit a true adventurer,” says Dave Barr, a double amputee from Bodfish, California, who rode a Harley-Davidson Shovelhead around the world in the early 1990s. “Today, none of us could replicate what he did then, so his was the motorcycle adventure of the century. I can only wish I’d had that same opportunity.”

Clancy made a formal start in Dublin as a tribute to his Irish father, and rode through Britain and much of Europe before crossing to North Africa and then sailing to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) via the Suez Canal.

“The Henderson was the most advanced motorcycle of its time,” says Craig Pallister, a founding member of the Vintage & Classic Motorcycle Club Hong Kong. “That said, Clancy would not have had the most comfortable ride, given the very thin wheels and minimal suspension. He would have been absolutely knackered most nights.

“He would also have had to be his own mechanic – punctures he could have fixed by himself fairly easily, but anything to do with the engine would have been more problematic. In all senses, it would have been an epic ride.”

Clancy crossed from Ceylon to Singapore, and having discovered he would be unable to ride to Hong Kong, he boarded another ship, landing in Victoria in March 1913. He had been expecting a city rather than the relatively modest port that Hong Kong was at the time. However, the inhabitants were anything but a disappointment.

The Chinese impressed me very favorably. They are quiet, respectful, courteous and neat

“The Chinese impressed me very favorably,” he wrote. “They are quiet, respectful, courteous and neat. All the ladies wore very becoming silk pantaloons, long embroidered coats and neat slippers […] several of them carried chubby, doll-like babies, with legs astraddle their sides or waists, and all seemed well and happy.”

Clancy had planned to motor up the coast to Shanghai, but as the few roads were in poor condition and infested with bandits, he elected to go by sea once more. Shanghai was an eye-opener – a rip-roaring cosmopolitan entrepot that was thriving in the wake of the revolution that had overthrown the imperial Qing dynasty.

Having toured the main sights, Clancy set out with a guide for a more authentic experience in the “native city”.

“A little later we came to a great iron door in a high wall,” he wrote. “The latchstring was not out, but some mysterious raps by the guide caused the door to slowly swing back on its hinges, revealing a dried-up old man and admission to the old Mandarin Tea Gardens of East and West.”

Clancy delighted in everything the gardens had to offer, relishing “queer limestone formations, archways decorated with minute figures, immense stone dragons, ponds filled with goldfish and a summerhouse [that] overlooked the whole enclosure”. He added, “Entirely deserted though it was, the garden was so purely Oriental, so absolutely unique in every detail, it would be impossible for a Western mind to conceive of it, or to originate any one of its countless weird, yet strangely beautiful designs. The Chinese are surely artists. I should have liked to sit there half a day and dream.”

Clancy was brought down to earth with a bump, though. The gatekeeper demanded money to let the visitors out, and declined the offer of the equivalent of 15 US cents.

“The rascal wanted more,” stormed Clancy. “My Savage [pistol] was in my suitcase at the hotel, or he would have changed his mind. Still, there were two of us to one of him, so finally he decided to let us through.”

That Clancy had chosen to include a 10-round semi-automatic weapon in his personal baggage, and contemplated using it to settle a petty dispute, can only be classed as signs of the times. His outbreak of temper – in contrast to his appreciation of the bucolic surrounds – may provide a clue to his character. Either way, his Shanghai adventures were not over.

Give China a little time, and she’ll not only have plenty of trunk roads, but one of the richest countries on the globe. Nothing can stop her

“Asking to be shown an opium den, I was told they had been entirely eliminated,” he wrote. “But the guide knew of one shopkeeper in the French Quarter who still smoked the drug and a little later we found him in full action […] He smoked rapidly, stirring the opium in the pipe with a small wire until it was exhausted. He seemed a very healthy individual, and full of business, offering to let me smoke for 20 cents, but I was not sufficiently tempted.”

Before sailing for Japan – where he found private motor vehicles were so rare that housewives frequently mistook the Henderson’s horn for that of an itinerant fishmonger – Clancy concluded his musings on China with a prophecy: “I liked both the Chinese and their country, and regretted our short acquaintance. Give China a little time, and she’ll not only have plenty of trunk roads, but one of the richest countries on the globe. Nothing can stop her.”

While Clancy remains relatively obscure in the travellers’ pantheon – even the National Motorcycle Museum in Anamosa, Iowa, contains only a few artefacts related to his circumnavigation – his heroics have inspired a select band of dedicated motorcyclists down the years.

“A friend [Gary Walker] and I rode around the world on BMW R1200GS bikes in 2013 to commemorate the Clancy legend,” says Geoff Hill, whose account of the journey, In Clancy’s Boots, became a bestseller. “Whenever we travel by motorcycle, we have nothing to think of when we wake but riding off down the road, unencumbered by regrets and concerns. Every day is still an adventure and a new beginning.”

San Francisco, where Clancy landed in May 1913, marked the beginning of the end of what newspapers of the time, with a notable lack of irony, called his “globe-girdling”. Fans turned out to greet him and a friend, Robert Allen, mounted on a Henderson 1913 joined him on the trip back east, which included a courtesy call on the Henderson factory in Detroit, before Clancy wrapped up the journey – estimated at 29,000km – in New York.

No broad highways criss-crossed the United States at the time, and Clancy lamented the state of the roads in northern California, eastern Idaho and western Montana, which he called “far worse than in any other country”.

In a slightly ponderous mood, Clancy summed up his final thoughts: “It would be difficult to overestimate the value of such a tour. In many countries I reached districts far from the lines of ordinary travel and was brought into touch with the great rank and file of the people.

“The traveller who wishes to obtain a true knowledge of living conditions must go where he is not expected, and this is what I always tried to do.”

Clancy had left the US with US$270, worked his way around the world, and proudly recorded he had US$200 when he got back to his starting point. In a flurry of clichés he wrote: “I’d started out a boy, and come back a man – where’s there’s a will there’s a way.”

Clancy was no one-trick pony. More or less as soon as he had finished his round-the-world jaunt he embarked on a career in the film industry, producing or directing numerous movies starring Will Rogers – the David Letterman of those times – before going on to make rather more sedate documentaries for the US Forest Service. He married the children’s author Eloise Lownsbery, in 1932, and – still passionately fond of motorcycles, but content with shorter rides – retired to the historic town of Alexandria, Virginia, where he died in 1971, aged 80.

“Few people have heard of Clancy these days, but he deserves a higher profile – what he achieved was nothing short of amazing,” says Hill. “To contemplate a trip like that was the act of a madman, and to complete it was the act of a hero.”