Museums in the West are full of stolen treasures – by visiting them are we perpetuating colonial-era violence?

- Among the artefacts on display in some of the best-known museums are pieces that were taken violently from their rightful owners

- In his book The Brutish Museums, curator Dan Hicks lays out the arguments for restitution – and the ways tourists can help

Professor Dan Hicks, curator of world archaeology at the Pitt Rivers Museum, in Oxford, England, is a sort of gamekeeper turned poacher.

Instead of fiercely hanging on to his museum’s collections, he thinks at least some of them should be given away, and especially those items that were looted, often violently, from their owners and whose return is now being requested by heirs or successors. And he thinks other museums should do the same.

“Each morning,” he writes in his recently published book, The Brutish Museums, “this morning for instance, as these museums are unlocked, the alarms turned off, the lights switched on, the doors opened to the public, to tourists and to school groups, this loss and violence is repeated.”

This is an alarming thought. If the violence of colonial acquisition reoccurs whenever the doors open, doesn’t that make the tourists who rush in part of the problem? After all, our entry fees help to keep the museums running, and where entrance is free our visits help justify government funding.

And some would argue it’s not just colonial pillage we’re supporting, but when we visit institutions that accept sponsorship money from fossil-fuel companies – the Science Museum, in London, for instance, or the Musée du Louvre, in Paris – we’re condoning the delay in significant action on global heating, too.

So when we’re once again allowed to travel, should we be boycotting at least some of these “world museums” and their alluring gift shops, and spending our money elsewhere?

Hicks’ museum – named after British army officer, ethnologist and archaeologist Augustus Pitt Rivers – houses more than half a million archaeological and ethnographical objects, from a stone axe that was still in use in Papua New Guinea in the mid-20th century to Roman shoes unearthed in Egypt that are around 2,000 years old. But in The Brutish Museums, he is particularly interested in the Benin Bronzes – more than 1,000 plaques cast with elaborate figures that were plundered by British forces from the shrines of kings in Benin, West Africa, in 1897. They are now found not only in the Pitt Rivers, but also in about 160 other museums, from Abu Dhabi to New York.

Hicks rejects the usually anodyne accounts of the bronzes’ acquisition, replacing them with an almost racy tale of blood, greed and fury, all wrapped up in a donnish discussion of the underlying principles behind demands for their restitution, and the weakness of contrary arguments.

The professor particularly objects when archaeology, ethnology and museums are put to work to promote a dubious view of racial superiority, as was the case right from the 19th century foundation of many of them – a view of cultural evolution that amounts to little more than a promotion of white supremacy: “Here are the objects produced by backward peoples, the peoples we beat, and the peoples to whom we are bringing the light of civilisation.” But it’s the curators, the administrators and the governments he wants to hold to account for this, not the customers.

Nevertheless, we have a supporting role to play.

“The main message to visitors is you’re never more than 150km away from a looted African object in the UK,” he says, on a video call from Oxford. “The decisions to return them are often in the hands of trustee bodies, or the governing bodies of universities, or city councillors. The visitors’ role in asking questions about provenance, asking questions about display, is central.”

Hicks says it can be difficult when an object has been collected and displayed to admit that it was wrong to do so. Some museums are taking rearguard action to slow the pace towards restitution.

One response has been to give a more frank account of how controversial items were acquired. The British Museum, for instance, now offers its roughly six million visitors a year stories of acquisition and ownership that, while exhibiting considerable caution, still acknowledge when objects were taken by violence as the result of colonial politics. This is particularly true where claims for restitution have placed objects – such as the Benin Bronzes, moai statues from Easter Island and the Elgin Marbles from Athens’ Parthenon – in the news.

For Hicks this is progress, but not enough. “The curator would love that you just rewrite the label, that you just recontextualise, that you put an interpretation board up. But that’s actually how you continue doing what you’ve been doing for 150 years.”

His book is a broadside against backpeddling, but when the dust and smoke have cleared, assuming his view triumphs, will there be anything in the most lauded museums left for us to see?

“Ninety-nine per cent of African objects taken to Britain … Well, we don’t even know what we’ve got. Some of them are in boxes that haven’t been opened for 100 years. Their state of conservation we simply do not know – they’re not on databases,” he says. “This is the reality.”

With material in museum storage often amounting to many multiples of that on display, should any main items be returned to the descendants of their former owners, there are plenty of non-controversial replacements.

Subsequent loans of artefacts may arrive from countries to which returns have been made, and indeed items do not necessarily vanish when their rightful ownership is acknowledged, but may remain on long-term loan.

Each claim for restitution has to be examined on its merits, and not all are valid. For instance, the demand often repeated in the Chinese press that every piece of the British Museum’s 23,000-strong Chinese collection should be returned holds no water, since most items were legitimately purchased before donation.

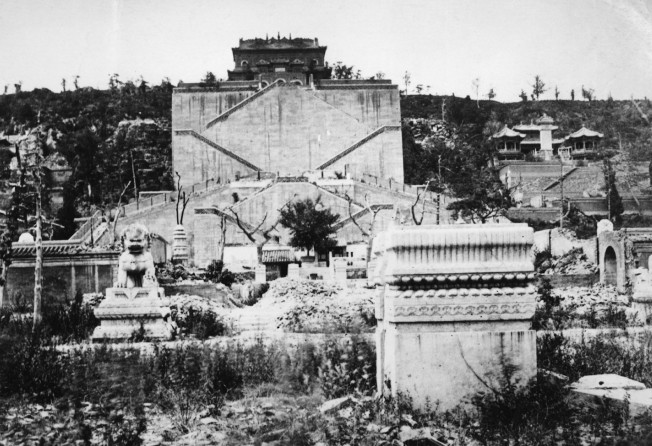

Claims that most or all of the items were taken during the notorious Anglo-French sacking of Beijing’s Summer Palace in 1860 are false – a glance at the museum’s website confirms there are myriad origins to the collection. Perhaps 15 pieces may be of Summer Palace origin, but there’s no way of telling, and even these 15 include bits of roof tile that might have come from one of many other contemporary buildings.

Hicks’ arguments resonate with Chris Garrard, a member of protest group BP or Not BP?, which mounts theatrical protests against fossil-fuel sponsorship.

As the parody of the Bard’s words in the group’s name hints, it began life arguing that Britain’s Royal Shakespeare Company should reject funding from fossil-fuel producer BP. Having succeeded, it has embarked on a drawn-out campaign to compel the British Museum to do the same.

The group has partly taken up the issue of restitution, too, sometimes operating unofficial “stolen goods” tours of the British Museum, in which guides amplify the histories of controversially acquired objects.

“Eight years of creative protests have steadily grown and grown from a small group of activists, to, in February [2020], having an occupation of the museum with one-and-a-half thousand people taking part,” says Garrard.

And when they parked a 30-foot wooden Trojan horse in the museum courtyard – in their view a perfect metaphor for BP’s invasion of this cultural citadel – most visitors found this thought-provoking and entertaining.

The concern here is that the sums needed to get a company logo onto a museum or particular exhibition are tiny fractions of oil companies’ total communications budgets. The social legitimacy gained is bought cheaply, and in some activists’ view, this is the British Museum sponsoring BP, not the other way round.

I think the kind of role for visitors is to ask questions, to critique, to challenge, to protest in the ways that we do as well, and to demand that the museum is accountable

Like Hicks, Garrard and his co-campaigners want to hold boards and management teams to account. Those bodies are shirking their responsibility to respond to the next big crisis we’re going to face in society, he argues.

“Our protests are carefully designed to engage people, to mobilise them, give a platform to communities who are impacted by BP, but we’re quite specific that we’re targeting the sponsorship. We’re not wanting to take down the curators or the people who work very hard within the museum, but trying to change the way the museum works and approaches many of these issues.

“I think the kind of role for visitors is to ask questions, to critique, to challenge, to protest in the ways that we do as well, and to demand that the museum is accountable,” says Garrard.

Hicks welcomes the debate. “Who’d be a curator if your only job is to unlock the museum at the beginning of the day and to close it,” he asks. “We are academic spaces. We’re places of knowledge. We’re public spaces. We’re places for society. We need these places desperately today.”

So when the opportunity comes again, do give these museums your support, but ask questions, and make your views known.