Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan’s reopening of 400km Trans Bhutan Trail restores ancient link between mountains and monasteries for Bhutanese and visitors alike

- The Trans Bhutan Trail was for centuries used to get between villages in the Himalayan kingdom, but fell into disrepair after roads were built in the 1960s

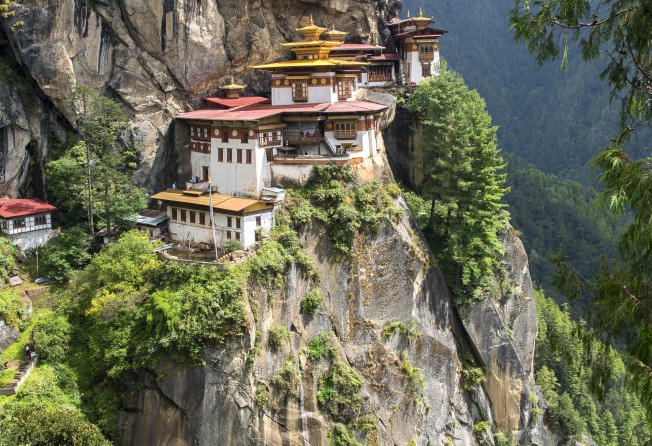

- Bhutan restored the 400km path during the Covid-19 pandemic. Now visitors can hike along it to the Tiger’s Nest monastery – look out for the photobombing monks

Quick, what’s the capital of Bhutan?

No, me neither, until recently – and I’m supposed to be a travel writer.

Thimphu is low key and likeable. There’s a handicraft market, a few modest boutiques and plenty of general stores, but you don’t come to Bhutan to go shopping.

You come to learn about Buddhist rituals from scarlet-robed monks and to venture barefoot into temples and monasteries. You come to gaze at the world’s tallest seated Buddha and to feast on delicious Bhutanese dishes. You come to hike along the Trans Bhutan Trail.

The Himalayan kingdom reopened its borders on September 23 after nearly two and a half years of Covid-enforced isolation. Tourists are back and there is renewed optimism in the air, thanks in part to a 16th-century footpath.

The Trans Bhutan Trail (TBT) was used by messengers and monks, soldiers and traders for centuries, until it fell victim to “progress”. The introduction of a national road network in the 1960s led to its rapid demise. Steps subsided, paths became overgrown and bridges collapsed.

Families, friends and farmers were no longer able to wander between villages and the trail closed. It would be some time before it reopened.

The new roads brought cars. Not too many, though; Bhutan is the only country in the world with no traffic lights.

And if you think that’s quaint, wait until you see the quirky roadside signs that encourage good driving habits: “Going faster will see disaster”, “Alert today, alive tomorrow” and “After whiskey, driving’s risky”. (English is the medium of instruction in the Bhutanese education system, which makes chatting to locals – as well as understanding the road signs – easy for English-speaking visitors).

Restoring the original trail meant drawing on local knowledge. While Covid-19 had the planet in its grip, the Bhutanese got busy. Meetings were held with village elders to help tease out details of forgotten pathways and crumbling Buddhist shrines. Furloughed workers cleared vegetation, 10,000 new stone steps were cut and bridges built.

TBT 2.0 is now open and the people of Bhutan can once again walk in the footsteps of their ancestors. I am among the first group of foreign guests invited to hike sections of the 403km (250-mile) route.

We loosen up with what should be a relatively easy downhill trek. I’m in no shape for anything too strenuous, though, and when our guide, Damchoe, offers to carry my day pack, I ask him to carry me instead.

I huff and puff past a troop of youths in bright orange uniforms who are using a chainsaw to chop down overhanging tree limbs. This isn’t mindless deforestation, however, just trail maintenance.

Bhutan is all about the long game – 71 per cent of the country is under forest cover and the constitution mandates to maintain at least 60 per cent in perpetuity.

The rebooted TBT is maintained by this army of youngsters. The De-suung, or Guardians of Peace, are a 30,000-strong volunteer force with responsibilities that range from firefighting and assisting at Covid quarantine centres, to keeping the ancient footpath in tip-top condition.

We complete our first section of the trail and spend the night at a campsite hemmed in by steep hills carpeted in dense evergreen forest. My tent is comfortable but it’s located near the entrance, a short distance from my fellow campers.

Bhutan is home to Royal Bengal tigers, bears and leopards and I sleep fitfully. The next morning, Damchoe chuckles and reassures me that none of the country’s toothy carnivores roam this corner of the country. It turns out I’ve more chance of being attacked by a leech.

Next to the campsite is Thinleygang Lhakhang. Perched on a hill and surrounded by trees knitted together by low-hanging clouds, the Buddhist temple is spectacularly photogenic – and that’s before a group of monks glides into the frame. It’s not the first time this has happened, either.

Whenever I take out my camera and compose a photo, a band of shaven-headed figures appear in the viewfinder. Perhaps they are working for the Bhutanese tourism board.

At our next stop, it’s even harder to keep monks out of our photos, but that’s because we’re visiting the Nalanda Buddhist Institute. My group head off for a talk on Buddhism but I hang around the courtyard with my hosts, drinking butter tea sprinkled with zow, a crunchy rice snack.

When one of them asks me for English Premier League football news, I’m happy to oblige. It’s not often I get the chance to offer enlightenment to a monk.

Another day, another early start. The official opening of the TBT is taking place at Simtokha Dzong, the nation’s oldest fortified monastery. Prince Jigyel Ugyen Wangchuck formally inaugurates the trail in the presence of political dignitaries, monks and the media.

Sam Blyth, founder and chair of the Bhutan Canada Foundation, the leading international donor for the project, reminds us that the TBT is not a tourist trail, although the people of Bhutan will share it with their international guests. Butter lamps are lit and then we all head outside to prepare for a hike.

The route leads us alongside a fast-flowing river bordered by a patchwork of emerald paddy fields and criss-crossed by wooden bridges. I fall into line with Karma Tshiteem, secretary of the Gross National Happiness Commission from 2008 to 2013.

The initiative, which was adapted from the internationally recognised gross domestic product (GDP) economic benchmark, has attracted global attention.

The former bureaucrat explains how the government is investing in its people and giving them more say in the running of their own affairs. He acknowledges that despite some success, there is still work to do in meeting the needs of development.

“Quality of living could be better but quality of life couldn’t be better,” he says.

Talking of which, the Bhutan government recently increased its Sustainable Development Fee – charged to tourists – from US$65 (HK$510) to US$200 per person per day, with funds directed back into communities to support health and education.

The levy, which does not include accommodation, food or entrance fees to sightseeing attractions, is also earmarked for the preservation of Bhutan’s cultural traditions and the funding of sustainability projects.

The terrain flattens out and, deep in a rhododendron forest, a farmer offers us freshly picked red apples. Next we’re offered steaming cups of tea and coffee at a rest stop and photobombing monks continue to materialise every time I get my camera out.

I ask one whether he thinks cable cars will one day link Bhutan’s mountains and monasteries.

“I’m 100 per cent sure they won’t,” he says. “We want to keep the place sacred.”

Karma continues to set a cracking pace while reminiscing about his time in public office. “When I was appointed, the emphasis was on building and improving motorable roads,” he says. “There were many villages where you had to walk three or four days to reach a highway. People had to carry their belongings on horses.”

With lungs burning and legs turning to jelly, I wonder whether I might be able to hire a horse for a couple of hours.

It’s my last day in the foothills of the Himalayas and our final hike proves to be the most challenging.

Taktsang Monastery is Bhutan’s signature sight. The Tiger’s Nest, as it is better known, appears on postcards and oil paintings, fridge magnets and jigsaw puzzles. If it sounds tacky and tawdry, fear not; the attraction draws hikers in their hundreds, rather than hundreds of thousands.

As usual, I feel woefully ill-equipped when comparing my outdoor gear with the rest of my group but I cheer up when I spot monks heading up in flip-flops.

The trailhead is 2,500 metres (8,200 feet) above sea level and soon after we set off, the air thins and my head begins to ache. Altitude sickness, perhaps, or too many bottles of Bhutanese beer the previous evening?

I power walk through the pain barrier and dodge herds of hurrying horses delivering food to the monastery. None slow down sufficiently for me to hitch a lift.

A cafeteria marks the halfway point, from where the Tiger’s Nest remains a distant white smudge shrouded in mist. As I’m congratulating myself on my stamina, the waitress explains that staff have to hike up to the cafe every morning, then walk down again after their shift.

Three cups of sugary tea later I press on. A series of sharp switchbacks delivers me to a vantage point a whisker below 3,000 metres. All of a sudden, I’m face to face with Bhutan’s most iconic landmark, which appears to be levitating but is actually wedged precariously into a vertical rock wall.

With impeccable timing, the clouds clear to reveal splodges of blue sky, and a medley of monks obligingly appear just in time to add a focal point to my photos.

For six days, Bhutan has educated and enchanted me. In an age of instant gratification, information overload and constant connectivity, the TBT provides a culturally rich antidote.

Values lost in other parts of the world are still in evidence in the Land of the Thunder Dragon – the people I have encountered have been unfailingly courteous and kind, and charmingly curious.

I have not been the speediest hiker on the trail, but walking at a relaxed pace and stopping to chat with passers-by has suited me. Besides, as the road sign says, “Going faster will see disaster.”

Tim Pile was hosted by the not-for-profit sustainable tourism enterprise Trans Bhutan Trail.