How Singapore got rid of corruption and cleaned up its act, illustrated step by step on the Graftbusters’ Trail

- Singapore ranks joint fourth on an index of the perceived honesty of its institutions but before the 1950s, corruption was not just common but widely accepted

- Walking the Graftbusters’ Trail helps explain how the city’s Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau fearlessly went after police and government ministers

Clutching expensive bags, wearing designer sunglasses and changing poses swiftly, one young person after another is photographed in front of a hulking old building in downtown Singapore.

The appeal stems from its window shutters, which are variously purple, blue, green, gold, orange and red. This flood of colour has made the building a prime backdrop for social media images, planting it on Singapore’s busy influencer trail along with locations such as Marina Bay Sands and Gardens by the Bay.

The building with the multihued shutters is the Old Hill Street Police Station, which is also a key stop on a more meaningful tourist trail, one that helps to explain Singapore’s affluence.

Many other nations have greater natural resources than the city state yet are comparatively unsuccessful. At the heart of their failure, all too often, is corruption.

When the era of self-governance began in Singapore, 63 years ago, the authorities cracked down on abuses of power for private gain, as I learn while following the Graftbusters’ Trail.

City tourist trails typically focus on themes with broad appeal such as food, nature, architecture and culture. By contrast, Singapore’s National Heritage Board has crafted niche routes centred on cemeteries, maritime history, military barracks and law enforcement.

More than 40 unique trails are listed on the heritage website, where route maps can be downloaded in English, Malay, Mandarin or Tamil. One of them is the Graftbusters’ Trail.

Singapore ranks equal fourth – with Norway and Sweden – on NGO Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, meaning it trails only Denmark, Finland and New Zealand when it comes to the perceived honesty of its institutions. Hong Kong is in 12th place, directly below Britain, which plays a central role along the Graftbusters’ Trail.

The route helps explain how Singapore evolved from being a city rife with corruption during the British colonial era to one of the world’s most honest nations. Much of the credit is due to the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB).

Admittedly, the trail is great PR for the Singaporean government, keen to showcase its trustworthiness and transparency, but it is also fascinating. And its compact nature and central location means it can easily be weaved into a busy day of sightseeing, perhaps while strolling between the National Museum of Singapore and tourist hotspots Clarke Quay and the Singapore River Walk. Five of its seven points of interest can be seen on a 1.5km (0.9-mile) stroll.

I start at the National Museum, a commanding neoclassical structure dating from 1887. The artefacts, text and audiovisual displays in the spacious Singapore History Gallery provide a strong sense of the colony in the generations after the British took over, in 1819.

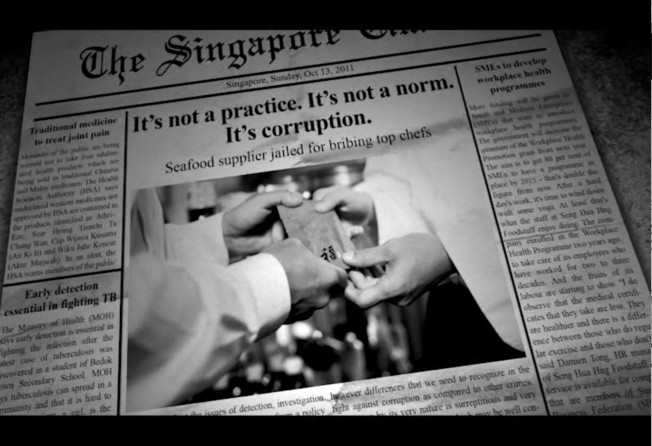

Corruption was not just common but also accepted. It wasn’t until 1871 that corruption became a crime. Even then, the law was barely enforced.

Throughout the 1800s and most of the 1900s, the police were central to the problem, according to a 2022 study by Jon S.T. Quah, a former professor of political science at the National University of Singapore.

During that period, the colonial government ignored systemic corruption within the force. The authorities also made the mistake (assuming it was, indeed, a mistake) of tasking police officers with investigating their own sins.

When Singapore finally made a serious effort to quash corruption, this played out largely within the Old Supreme Court. Set between the National Gallery and the comprehensive Asian Civilisations Museum, this stately neoclassical building is passed every day by many Singaporeans who are perhaps unaware of its key role in the tale of their city.

It was here that the nation’s so-called Graftbusters was born in 1952, 22 years before Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption was formed for many of the same reasons.

The CPIB was established as a unit of 13 investigators, the Graftbusters’ Trail website explains. Their office was purposely sited within the Supreme Court building in a gesture that signified fighting corruption was now a national priority.

The colonial government’s hand had been forced by a major controversy the previous year, when several police officers were found to be complicit in a huge opium racket. The CPIB’s independence from the police force allowed it to quickly uncover extensive corruption within Singaporean government agencies and law enforcement departments.

By the end of the 1950s, the CPIB had become even more feared.

In 1959, Singapore ceased to be a British colony, achieving self-government. Under new prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, the Prevention of Corruption Act was enacted, boosting the power of the Graftbusters.

The CPIB expanded and soon needed its own premises. Only a plaque marks the bureau’s presence in the three-storey building at 81 Stamford Road, which is now occupied by the Singapore Management University. From 1961 until 1984, the CPIB office here was known as the White House, not due to its appearance but in reference to the assumed pure intentions of its officers.

However honest they may or may not have been, CPIB staff exposed a torrent of corruption. In the 1960s and 70s, they focused heavily on police who accepted bribes to protect brothels, opium dens, gambling syndicates and drug smuggling cartels.

In one 1968 case alone, they prosecuted 67 police officers working for a gambling gang. Operation Chap Ji Kee was undertaken together with the Criminal Investigation Department and targeted syndicates controlling the chap ji kee lottery, which was popular with housewives.

Then, in 1975, the CPIB took down a government minister, Wee Toon Boon. Wee was found guilty of using his influence to give advantages to an Indonesian businessman in return for a bungalow and the land it stood on as well as seven first-class tickets to Jakarta for an all-expenses-paid holiday for his family. He was sentenced to four and a half years in prison.

That scandal burnished the reputation of the Graftbusters and highlighted the Singaporean government’s determination to target corruption, even among its own ranks.

By 1984, the growing CPIB again needed more spacious accommodation, this time in that photogenic influencer magnet on Hill Street.

By this time, the bureau was no longer focusing primarily on police and low-to-mid-level government staff. It was now going after some of the country’s most influential people.

During its 14-year stint at Hill Street, the CPIB arrested a government minister (minister for national development Teh Cheang Wan was investigated for accepting bribes but committed suicide before he could be charged); senior members of the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation; and the deputy chief of the Public Utilities Board (Choy Hon Tim was sentenced to 14 years in prison for accepting the largest amount of bribes in Singapore’s history: S$13.85 million).

By the time the Graftbusters moved into their fourth headquarters, on Cantonment Road, in 1998, Singapore had become one of the world’s least corrupt nations. Prosperity had followed the clean-up. From 1986 to 1996, Singapore’s economy grew at an average of 12.8 per cent a year, according to government data.

In 2004, the CPIB shifted again, to another stop on the Graftbusters’ Trail — its current Lengkok Bahru hub. The hub is a hulking, cream-coloured building guarded by high perimeter walls and CCTV cameras.

At that stage, the Supreme Court, where many of the CPIB’s cases were heard, also had a new home. Situated opposite the Parliament of Singapore, this is one of the city’s most distinctive structures. A modern building topped by a glass dome that looks like a UFO, it was constructed in 2003 from translucent rosa aurora marble.

The court’s design supposedly signifies transparency of law, also reflected in its open-plan layout and the natural illumination from its atria and skylights.

This huge, stately building has witnessed many a corrupt official meet a grim fate. Breaking Singapore’s anti-corruption laws can incur a S$100,000 (US$73,000) fine or five years’ jail, or both. The CPIB doesn’t mess around.

It’s better to interact with the Graftbusters from a safe distance, as I did, by following the walking trail that helps explain how they hunted the corrupt and cleaned up Singapore.