China’s ‘Spicy Mums’: luxury-spending powerhouses who live by word of WeChat groups

No price is too great – whether on education, experiences or clothes – as rich mainland parents strive to ensure their children achieve elite status in life

The development of China in the past decade is most easily visible through big numbers.

Yet statistics such as “Chinese travelling overseas increased by 1,380 per cent from 2000 to 2017” do not help to understand the intricate changes in society that have taken place.

One of these enormous (seismic, tectonic, however far you want to go) changes is in the new parenting culture of China’s affluent millennial generation.

The more traditional aspects of Chinese parenting culture are clear: a one-child policy, parents who feel the need to pressure their child into intensive study, Einstein-level mathematics, weekend classes and the like, with grandparents and extended family all colluding into the alleged “Little Emperor” culture.

The new lifestyle, opinions and expectations of China’s millennials and their influence as the drivers of luxury consumption, should now be well accepted by anyone who reads about global luxury.

But now these millennials are also parents – China’s new generation of modern parents, living in globalised cities and travelling internationally at will.

Just five to six years ago it was not uncommon to come across hotels in Shanghai that labelled themselves as “business hotels”, which were not interested in the “family” sector.

Only a few specialised shopping malls had sections for children’s play areas and the like.

In 2018, practically every single 5-star hotel offers children’s amenities, menus and activities, while countless shopping malls and other businesses now compete for family visitors with global names such as Peppa Pig and Dora the Explorer tagging along.

In luxury, brands are eager to capture the new Chinese family: Baby Dior campaigns strongly, China has the most Burberry children’s stores in the world and Fendi Kids opened in Shanghai’s Plaza 66 in 2017.

Millennial parents not only demand but expect special organic food, imported children’s furniture, with “baby MBAs” and ‘Olympic mathematics” yet more angles on the drive of furthering the lifestyle of their mini-me.

How is this new demographic of the affluent, modern Chinese parent evolving, and what must luxury brands know to connect with them?

China is approaching a boom of millennial mamas – or in their own words, “Spicy Mums” aka “Hot Mamas”. They are the new generation of post-1990 mums that maintain an image of both hot and cool.

To understand this new demographic of the affluent, modern Chinese parent, luxury brands should be aware of the size of this social shift.

Imagine the difference in parenting in the West, between those born in the 1930s or the 1960s.

We are talking about the first generation of parents that are asking new questions about parenthood, rather than simply accepting what was done before.

Post-90 Spicy Mums think, shop and raise children very differently than previous generations.

A 2018 report on Chinese millennial mothers’ shopping behaviour from CBN Data and a 2016 “Maternal Marketing Whitepaper” share similar insights on this new demographic.

The reports suggest that:

- They feel entitled to self-care and self-love. They see investment in premium brands as a necessity for themselves and their children.

- They turn to other millennial mothers, rather than their own parents, for parenting advice.

- They are less sensitive about price and more concerned about product safety and quality.

- They love to shop for high-quality children’s products via cross-border e-commerce.

The competition: parenting to win

As the clearest indication of the thoughts of this demographic, one simple comment from a mother went viral on WeChat last year.

The piece was titled “A Monthly Salary of 30,000 yuan (US$4,493) is Not Enough for My Child’s Summer Vacation”.

Written by a highly-paid executive mother, it told the story of how she could hardly keep up with the extravagant overseas summer programmes that she lined up for her daughter.

The mother said that the total cost of her daughter’s education over the summer was 35,000 yuan (about US$5,240), including 20,000 yuan for a 10-day US study tour and other tutoring classes that cost up to 10,000 yuan – and that she was compelled to do this as all of her peers were doing the same.

With the country’s digital boom, new Chinese parenthood is also digitally integrated.

These Spicy Mums form their communities mostly through dedicated apps and WeChat groups.

Babytree, an online community with more than 20 million millennial parents, is among the most active sites. QinBaobao (or “kiss baby” in Chinese), is a popular app for these parents to exchange parenting ideas, and post photos of their babies without the social pressures of mixing life or work contacts in WeChat.

In these e-parenting communities, Haitao, meaning cross-border e-commerce, is frequently brought up: how to source safer, better products than the domestic options in China is a primary concern for such parents.

Key-opinion-leader parents hit key cultural pointers

The demographics’ economic capacity to spoil their children, combined with a lack of generationally consistent parenting knowledge, have given rise to a wave of parenting key opinion leaders across social media.

Among them, “ZhouYueyue” makes illustrations about a typical young mum’s experience, striking a chord with many. “NicoMama”, who shares more practical information graphics and healthy cooking tips, is deemed as a “mum authority’”.

There is plenty of space for niche content, too.

“Nakikorose”, who brands herself as a “maternity and child sleep consultant”, seems to attract parents in a higher income bracket.

Content perceived to be scientifically credible, or myth defying against the long-standing parenting superstitions in Chinese society is popular among post-90 Spicy Mums.

Filial piety remains strong among all in China – at least, part of it.

Millennial parents bring their own parents with them on holidays, family celebrations always involve gifts and blessings to their elders and they are still nonetheless keen to have willing babysitters.

Yet they still consider that the instruction of the older generations may be based on ancient theorem – a mismatch with their otherwise international lifestyle and knowledge.

The spending power of Spicy Mums is booming. From children’s fashion, enrichment classes, to preschools that promise a “holistic” educational approach, there are a few main buying trends among China’s modern parents.

1. Luxury children’s wear – ‘mini-me’, but also ‘better-me’

A quick view on social media can reveal that Spicy Mums love nothing more than dressing in similar outfits to their children and posing alongside them for an “Aren’t I cute, too?” selfie. Smart brands are wise to this.

In May 2018, Dior posted pictures of child celebrity Heidi Cui in a Baby Dior dress in Cannes.

Heidi gained public attention as a result of her role in the reality television show Where Are We Going, Dad?.

This image combines youth with popularity and success – three traits which are catnip for Spicy Mums.

[Chinese[ Spicy Mums love nothing more than dressing in similar outfits to their children and posing alongside them for an ‘Aren’t I cute, too?!’ selfie. Smart brands are wise to this

Luxury children’s wear is nothing new to the affluent Chinese market.

D&G, Gucci, Baby Dior, Burberry and French luxury line Bonpoint have been the capsule wardrobe for wealthy Chinese children.

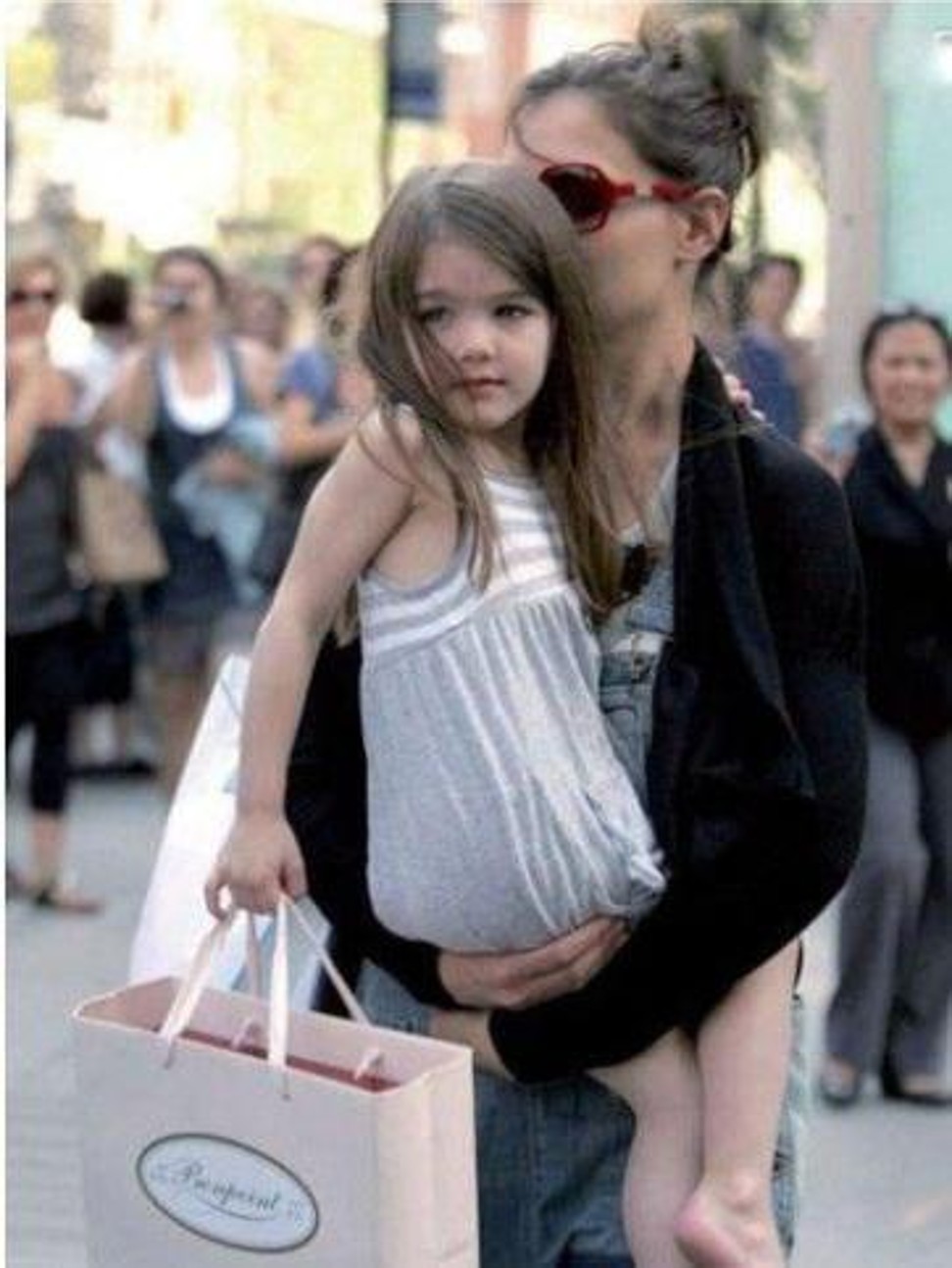

The practice of using celebrity children’s street styles to raise brand awareness, however, is particular to the Chinese market.

China’s children’s fashion websites and magazines’ main content are celebrity children’s styles, especially street styles shot by paparazzi.

What Suri Cruise – the daughter of actor Tom Cruise and actress Katie Holmes – the Beckhams, and other celebrity children are wearing in their day-to-day life become the fashion bible for millennial Spicy Mums.

The West has given a name to the demand for luxury children’s wear – “the mini-me trend”. In these more mature markets, luxury children’s wear consumption is led by the parents’ desire to channel their personality through their children.

A cool, well-dressed child is a manifestation of the parents’ good taste.

This trend is still in the embryonic phase, with affluent Chinese parents shopping for their children by looking at leading Western celebrities, dressing them in ways that they never could have achieved in their own youth.

The trend is fertile branding ground and shows long-term opportunities.

2. Experiences for both – ‘look what a good parent I am’

Luxury children’s fashion, imported organic food supplements – these are the new normal for China’s millennial parents.

Beyond the luxury purchase, they now seek experience, preferably with their own participation ready to be posted on their social media.

Baby swimming is one example. China’s first-tier cities have witnessed a boom in baby swimming clubs that charge more than 10,000 yuan for an annual membership.

The sport was spotted on Chinese celebrities’ social media, and then publicised as the choice of all smart parents such as Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and actress Ziyi Zhang.

Loong Swim Club, a market leader, has expanded all over China, emphasising its “German origins” to assure Chinese parents that it must be worth the fee.

It has included a German flag in its logo header, and a European Union distribution network on its homepage.

Like other swimming clubs, Loong uses social media to tell parents how baby swimming helps to develop a child’s social skills and increase their confidence. For many young parents, these promised advantages are worth the hype.

Four Seasons Hotel, Pudong, Shanghai and Hyatt On The Bund Shanghai have started to offer premium swimming classes for children in their pools – another indication of the changing expectations of their guests.

All aspects of an affluent lifestyle should involve the child, including dining at 5-star hotels.

The Peninsula Hotels in Shanghai and Beijing are well aware of the family aspect as a draw. Last Christmas, The Peninsula Beijing offered experiences such as baking biscuits and decorating trees together.

Along with the luxury elements such as Champagne for the parents and Christmas drinks for children, the focus was on the creative, social activities done as a family, learning about a “Western” holiday and ripe in plentiful photo opportunities for the parents to share on their WeChats and Weibos.

The “togetherness” side also has an aspect of “I’m a big kid, too” (aren’t we cute together?)

Would parents in the West want to buy Disney items for themselves? Perhaps not.

Yet millennial Chinese parents are young-at-heart – proved by the ubiquitous “gamification” seen across many luxury brands.

These parents want to be “part of the fun” themselves. One example was luxury fashion brand Coach collaborating with Disney (Coach x Disney in trendy terms) in a “magic mirror” on their WeChat accounts.

The launch of their “A Dark Fairy Tale” collection contained all of the current methods of interaction – short videos, the ability to interact with the AI “mirror” and offline events related to the game – all targeted at adult buyers.

3. ‘Holistic’ preschool

The Chinese phrase “赢在起跑线上”, which literally translates as “win at the starting line”, summarises the prevalent parenting ethos in China.

Even for the affluent, the “culture of scarcity” feeling remains ever-present.

With such a big population, the competitiveness and need to be sure of “not losing out” is right at the pulse of cultural behaviour.

While the need to ensure one’s children have the best education is recognisable in any demographic worldwide, the desire is distinct in China.

While a wealthy family in Britain, for example, may feel confident that their child can go to the “right” kindergarten and school, the urge to ensure that this is the case is the baseline of any affluent Chinese parent.

The clothes, the lifestyle and more are desired, while the educational aspect of making sure their child keeps up with their peers is the very raison d’être.

As a result, premium preschools with a “holistic” educational approach, promising to turn children into smart, kind and confident individuals can set their own price.

Willpower Royal British Education is one of many “holistic” preschools that cost well over 200,000 yuan per year in Beijing.

The preschool has made a list of advantages to justify the cost: organic food with made-in-England silver cutlery, state-of-the-art facilities, bilingual education and proper play time.

The kindergarten also offers training courses such as horse riding and golf, hobbies that are traditionally associated with privilege.

“International schools” are not available for Chinese passport-holders, but the most affluent segment of Chinese parents may live abroad (or send their child abroad to do so) for the number of years required to gain a foreign passport, before returning to study at an international school in China.

Even for Chinese passport-holders, these international schools have now created “bilingual schools”, still in their name, for example Wellington or Dulwich having a separate school which can accept Chinese passport-holders, at the same annual school fee of more than 200,000 yuan

Such a “holistic” approach that combines study and play is considered a luxury in Chinese education.

For millennial parents, the internationalism and social aspects are extremely attractive.

They believe the craft courses, sports lessons, and social time with peers from similarly privileged backgrounds will give their children an edge from early on.

Little Star Group, which manages high-end children’s wear brands, such as I Pinco Pallino and YeeHoo in China, offers exactly such programmes to millennial families.

Chinese millennial parents believe a ‘holistic’ approach, which promises to turn children into smart, kind and confident individuals … is a luxury in Chinese education … classical music is good for creativity, horse riding for chivalry, golf for calmness and sailing for ambition

The brand group has a special club space for its VIP members – Little Star Club.

VIP families can join the activities in Bund 27, a prestigious address in Shanghai.

Not only that, but the club offers social training: classical music, horse riding, golf and sailing courses.

Every activity is described as enhancing children’s character. Classical music is good for creativity, horse riding for chivalry, golf for calmness and sailing for ambition.

One 28-year-old Spicy Mum told The Luxury Conversation: “If my child grows up in this environment, his life vision and perspective will all be better.”

With a British kindergarten degree, her six-year-old boy has already secured a spot in a competitive elementary school in Beijing.

China’s Spicy Mums are big spenders when they are convinced the value is there.

Among the growing competition for this sector, the question is only whether they find your offer attractive or not.

The Luxury Conversation takeaways:

- Affluent mothers in China live by the word of WeChat groups. All keen to be in a WeChat group with their social peers, there is often one “leader” who makes recommendations based on what celebrities are doing on Facebook and Instagram. The Spicy Mums are keen to follow the trends set by celebrity parents and children. Instagram is accessed by VPN in China and is worth exploring to engage with these globally-versed mamas.

- Everything is education. Everything is betterment, upgrading … and basically showing off just how elite your children (and therefore you) are. Create a reason/purpose for the luxury.

- Elite children are “all access”. Dinner at a three-star Michelin restaurant? It is a family affair with the family’s little Princess or Prince sampling the degustation and comparing it with other food they have tried worldwide.

- The upgrading and the luxury should not be arbitrary – the ideal offering is to collaborate with a renowned education, institution, celebrity or other brand. Holding a cooking class in your hotel? Then give the little chefs a Cordon Bleu certificate afterwards. Promoting a healthy life? Then engage with one of China’s Olympic athletes for photo-opportunities. There should always be a famous badge, flag or face to attach to the activity as a mark of elite success achieved.

- For the “right” investment in their child’s experience, there is no limit for affluent Chinese parents. No price is too great if it will deliver the truly elite, WeChat post-worthy moment for their child.

This article originally appeared on The Luxury Conversation.