How Akira and Blade Runner predicted the neon urban ugliness of Tokyo and Hong Kong in 2019

Dystopian and eerily prophetic movies Akira and Blade Runner – both set in the year 2019 – inspired Tai Kwun’s new multimedia exhibition ‘Phantom Plane, Cyberpunk in the Year of the Future’ (and it’s super Instagramable)

When was the last time you went an hour without looking at your phone? Do you break out in a cold sweat when your social media feed won’t refresh? Are we really in control of these machines, or is it the other way around?

Today’s hyper-connected world of AI, IG, cyberwarfare, drones and mobile phones is exactly the kind of nightmarish dystopia science fiction storytellers dreamt up decades ago – so it’s jolting to realise we have officially arrived in the fabled future of fiction.

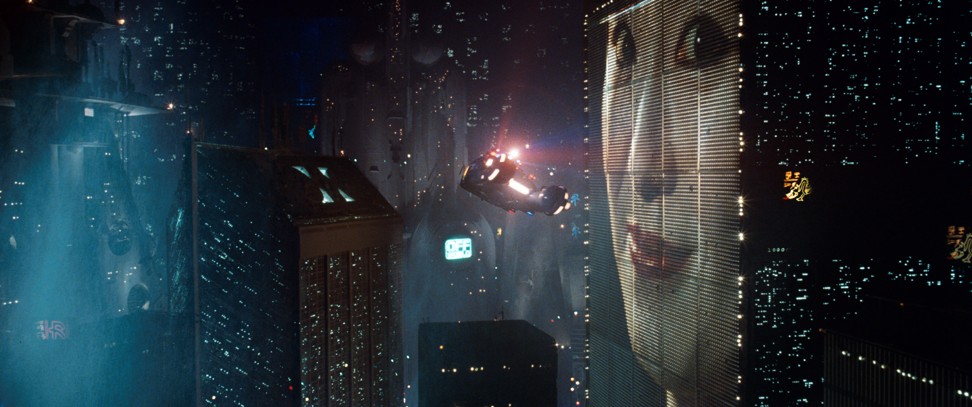

Two of the most influential sci-fi visions ever realised are both eerily set in the year 2019: Hollywood’s blockbuster Blade Runner and Japanese animation Akira – two seminal films that might skirt the East/West schism, but both clearly draw their imagined urban environments from Asia’s sprawling mega-cities. Or should that be “meta-cities”?

Produced six years apart, in 1982 and 1988 respectively, but with beguiling parallels in their depiction of an imagined 2019, both films are the jumping-off point for a synapse-firing, new multimedia exhibition at Hong Kong’s Tai Kwun.

Pause. . . . Shot with #sonya7ii #sel35f28z @sonyhongkong #sonyhongkong #sonyhk_daysandnights

A post shared by Jason J (@jason_x.j) on

Set in dystopian future versions of Los Angeles and Tokyo respectively, both films are today recognised among the most prominent examples of “cyberpunk”. While technically defined as a niche sci-fi subgenre, cyberpunk’s hi-tech, low-life aesthetic has today been readily appropriated into pop culture iconography exemplified in the widely-adapted novels of Philip K. Dick and endlessly riffed-on The Matrix movies.

Something about cyberpunk’s runaway, invasive-tech and scarred-planet scenarios clearly chimes with the climate crisis, divisive populism and simmering public revolt of the present day – as evidenced by the success of this year’s blockbuster Alita: Battle Angel, a Hollywood adaptation of the classic 1990s manga, and 2017’s Blade Runner 2049 sequel.

And with a live-action Akira remake in the works – Thor: Ragnarok director Taika Waititi is confirmed to helm – interest in Tai Kwun’s timely “Phantom Plane, Cyberpunk in the Year of the Future” exhibition is naturally piqued.

Strolling the surreal show’s three floors, it’s jarring how readily truth blends with fiction, reality with imaginary. Dominating the stretch of one wide wall, Japanese photographer Takehiko Nakafuji’s stark, angular, black and white city scenes appear as if stills from a classic cyberpunk film. Flecked with harsh cinematic light gleaming from extreme weather-soaked surfaces, they are actually documents of Hong Kong and Tokyo in the mid-90s and today. Time stands still in black and white.

The archetypal-imagined technology which became a reality might be the hologram, which Hong Kong multimedia collective Zheng Mahler powerfully uses in The Master Algorithm to conjure a morphing image of Qiu Hao, the world’s first virtual, artificial intelligence newsreader, unveiled in mainland China last year. Meanwhile the deadening self-reinvention of social media is invoked by US-born artist Sondra Perry’s Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation, which presents an unnerving automated avatar of its author strapped above an archaic exercise workstation.

Reality consistently intrudes on the imagined fiction, probing where the filmmakers got things right – but humanity perhaps didn’t. A world where body and machine are increasingly integrated, and corporate greed and technology are a source of urban alienation, not enlightenment.

Dating from the 1980s, US-born multimedia artist Tishan Hsu’s three-dimensional portraits (Terrain, No Name and Stripped Nude), depicting human body parts contorted with metallic grids and furniture items, seem like an eerie vision of whatever Google is cooking up after its watches and glasses. From a decade later, Tetsuya Ishida’s Interview (1999) sees the Japanese artist imagine a man being cross-examined by three human-faced machines – surely the next step for automated border control worldwide.

The modern cityscape is consistently invoked as a source of terror, not wonder. In Zheng Mahler’s large-scale Nostalgia Machines – a looming 15-minute animated video installation surrounding the entrance which visitors must enter under – skyscrapers are presented not as idealistic signs of progress, but “invaders” in opposition to the authentic street scenes below.

Sitting at the centre of the first room, South Korean artist Lee Bul’s huge hanging glass sculpture After Bruno Taut (Beware the Sweetness of Things), recalls the shape and sheen of glass skyscrapers – offering a brittle reflection to the viewer that chimes with our disconnected, self-absorbed realities. In a similar way, Shanghai-born Cui Jie’s three stark white sculptures recast real-life mainland buildings, such as the postmodernist East China Electric Power Buildings, crystallising these towering structures as imposingly, not inspiringly, futuristic visions.

Zooming down to street level, the most self-consciously Instagramable exhibit is surely Japan-born Shinro Ohtake’s huge installation Mon Cheri: A Self-Portrait as a Scrapped Shed, a real snack kiosk and caravan dumped in the gallery centre. Overflowing with treasured garbage, it will sound alarms with any pop culture hoarder living in a densely populated, high-rent metropolis such as Hong Kong.

A ready shorthand for Hollywood to invoke the post-global imagined future, Hong Kong’s bright lights and jumbled skyscrapers have long served as a sci-fi screen touchstone, and the city is never far from the frame here, too. Spread over the walls of a linking corridor with the irreverent disdain of a dive bar washroom, Hong Kong photographer Chan Wai Kwong’s pink-lit, monochrome snapshots of the densely populated Sham Shui Po, Yau Ma Tei and Wan Chai neighbourhoods teem with a cinematic squalor all the more unnerving for its verité nature; streets lined with smashed televisions, dismembered mannequins, tattooed Triads, loose women and, of course, plenty of neon. A recurring theme is the faces of children – eyes wide, perplexed, unnerved, enlivened, invigorated … but tarnished?

Despite being pieced together from footage mainly shot in Istanbul, Canadian-born artist Jon Rafman’s Neon Parallel 1996 – a cyber-noir, “lost vaporwave” mini-movie which plays on surveillance anxieties – conjures the metallic sheen, “electronic markets, high rises and never-resting streets” of Hong Kong, tellingly indicative of how homogeneous our cities have become.

Commissioned especially for the show, Japanese former graphic designer Hiroko Tsukuda reimagines “Asia’s World City” as a dense, claustrophobic, monochrome mesh of concrete street scenes, intended to draw parallels between “a fictional apocalypse and anxiety of our times”. While the curators couldn’t have imagined how 2019 would unfold, it feels a fitting portrait of a city scarred by petrol bombs and tear gas on a weekly basis.

At the centre, rows of cramped lifts appear to evoke both the ease of ascent but also restricted freedom – both physically and mentally, with only one route an option. Tellingly, the idyllic openness of Victoria Harbour is manhandled into a tiny top right corner image, scrunched behind inflexible metal bars.

Most meta of all might be Irish-born Yuri Pattison’s specially commissioned video installation False Memory, which offers a virtual walk-through of a real-life reimagining of Hong Kong’s infamous Kowloon Walled City – the lawless mini-state demolished in 1994 which has served as a reference point for dystopian scenarios so common to cyberpunk genre – reconstructed as a themed Japanese gaming arcade. The circles of past and future, real and imaginary, truth and fiction all close here. And the future looks anything but bright.

The Tai Kwun exhibit will run until January 4, 2020.