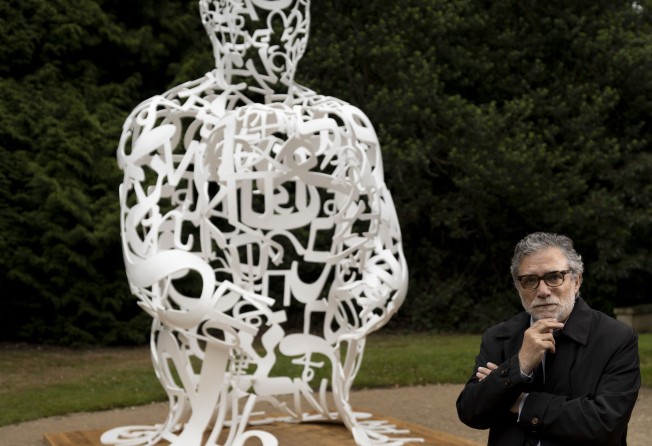

Spanish artist Jaume Plensa on art in the era of NFTs: the celebrity sculptor demands his public works be important, democratic, beautiful ... and he invites us to look AND touch

- His drawings are on show at the UK’s Yorkshire Sculpture Park and the Picasso Museum in Antibes, France, while his sculptures have been displayed in London, Chicago, Paris, Dubai and Tokyo

- He is best known for large-scale, poetic public works such as Soul in Singapore, Water’s Soul in New York, Possibilities in Seoul and House of Memory in Shanghai

Jaume Plensa has no concerns about appearing unfashionable when it comes to his view of what art is really all about.

“I think beauty is the soul of art,” he says, unequivocally. “Art has this tremendous importance, especially in the sense of introducing [beauty] to people’s everyday life. Of course, we can discuss what beauty means and that may be different for you than for me – but I think everyone has some conception of beauty in the back of their brain … and when you’re in front of it, you know it.

“There’s this idea [in the art world] that to talk about beauty is anachronistic – that it belongs to the past – an idea that I completely disagree with,” he adds.

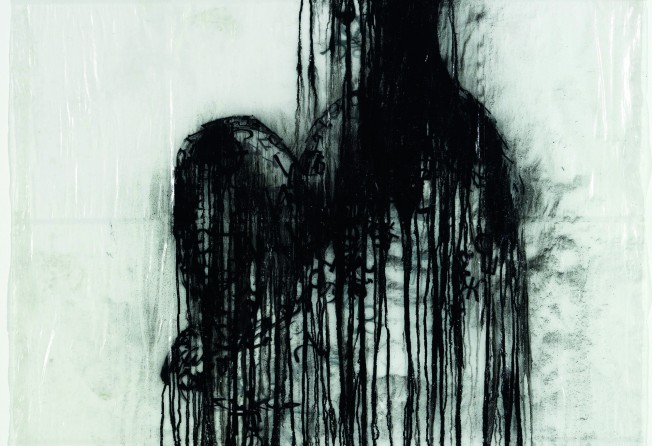

The Spanish artist’s philosophy is clearly expounded in his sculptural works in a variety of materials – alabaster, stone, glass and steel – but also unconventional ones like water, light and sound. His work can be delicate and intimate, as with his collection of drawings, now on show at the UK’s Yorkshire Sculpture Park and the Picasso Museum in Antibes, France, but he is best known for his large-scale, poetic public works.

Any art show these days has to have plenty of text explaining what each piece is about, and I’m not sure that’s a good thing

Spot them in Singapore – that’s his Soul at the Ocean Financial Centre; in Seoul, with his Possibilities; or in Shanghai with his House of Memory. He’s also had major pieces displayed in New York, Chicago, London, Paris, Dubai, Toronto, Nice and Tokyo. His pieces are hard to miss – indeed, one characteristic of many of his best known works is their sheer scale.

Last October he unveiled Water’s Soul in Newport, Jersey City, right on the Hudson River. The piece is 22 metres tall but, as he points out, with Manhattan as its backdrop, that’s not so big. Setting them within the urban environment makes the scale of his public artworks all the more important, he argues. Not that he uses the term “public art”.

“When city councils and critics and the like speak of ‘public art’ to me it sounds like they’re suggesting it’s in some way second league, or not strong intellectually – because ‘public art’ is strongly related with the kind of works you find on roundabouts,” he laughs.

“I prefer ‘art in public spaces’ because when you place a piece in that context you have to have a dialogue with the space, with the community and public areas, which are incredible places to develop art in a more democratic way. There is also an incredibly important return to society [through art in public places], because I think people have a hunger for beauty where they live.”

But public art matters, he adds, because art matters, and yet there are a lot of people for whom visiting art galleries just isn’t on their agenda: this is a way for them to experience art in ways sudden and unexpected. “They may not have any art knowledge, but there it is, and it can transform the way they look at the landscape,” he says.

“Suddenly this little touch transforms what you thought you knew already.”

Yet he can appreciate why so many wouldn’t consider visiting a gallery as time well spent. Art, he says, should be enigmatic, yet we live in times when gallerists are over-keen to explain a work’s meaning and often in ways that complicate, obfuscate and, ultimately, put people off.

“Any art show [these days] has to have plenty of text explaining what each piece is about, and I’m not sure that’s a good thing,” Plensa exclaims. “When you go into a library you can recognise a book as a book without knowing what it’s about or whether you like it.

“And perhaps the problem is that sometimes today it’s hard to know whether something is meant to be art or not without the context of a museum or gallery, and the text to say it is. I prefer to know myself whether something is art or not, and whether it’s good or bad. Sometimes the explanation just kills that enigma.”

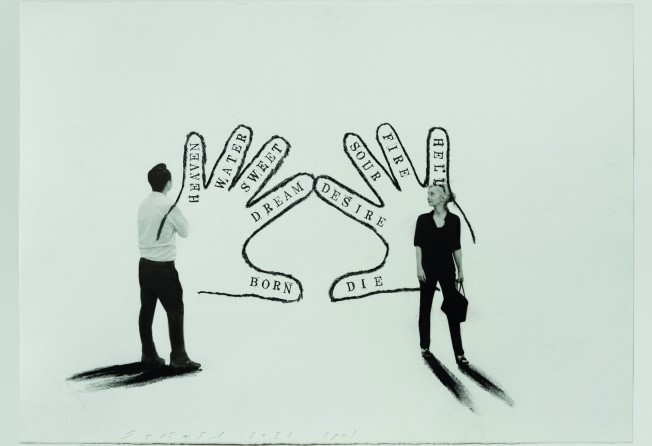

As a sculptor, first and foremost, his work isn’t limited in its appeal to the visual either. Plensa is keen for people to do with his public art what gallerists are rarely keen for visitors to do with those pieces in their careful white boxes: to touch them.

I’m convinced that sculpture is the only medium through which you can express that which is invisible, mystic – that which can’t be touched but which is always about us

He remembers giving a lecture at the opening of a show some years ago in which he spoke of the importance of interacting with his work. A woman in the audience took him to task. In that case, she asked him, why did his pieces come with the usual “Please do not touch” signs?

Plensa had to correct her. Read again, he implored. The signs say, “Please do not touch … Caress.”

It’s a return to a more ancient, less precious view of art as intriguing, inviting and inclusive – less the remote asset class from which we must keep our distance. But then, says Plensa, sometimes it can seem to him that just being a sculptor in a world of NFTs is rather out of keeping with the times.

“It always seems that sculpture is perceived as something that’s coming from the past, not a medium of the future, but my opinion is probably completely the opposite. I’m convinced that sculpture is the only medium through which you can express that which is invisible, mystic – that which can’t be touched [figuratively speaking] but which is always about us,” he enthuses.

“It’s like religion in its attempt to embrace those big questions that come up generation after generation. I think sculpture has that capacity because it stands apart from the everyday nature of life.”