Berlin’s fine dining scene fuelled by Brexit, start-ups and fintech

Twenty-eight years after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, a wave of gastronomic confidence is sweeping across the German capital and the hype is not just about bratwurst and beer.

When White Guide, a leading Nordic restaurant guide, introduced its dining app 12forward in late 2016, it picked Berlin over other German cities for its inaugural global launch, touting the city’s “cutting- edge” cuisine in “Germany’s fast-evolving radical food scene”. “Without a doubt, Berlin is Germany’s dining capital,” says Per Meurling, a Berlin-based food writer and the contributing editor of 12forward Berlin. “Other cities are years behind the level of quality and innovation we see here.”

Meurling, who is from Sweden, adds: “Since the wall came down, Berlin has transformed into a refuge for the creative class of Europe, and we have seen a massive influx of the brightest and most colourful people from – and outside – the continent.”

He says it helps that it is relatively easy and cheap to start a business in Berlin compared to other European capitals. “The city is very large and relatively unexploited, which leaves a lot of new neighbourhoods to explore for businesses.”

Billy Wagner, founder of Nobelhart & Schmutzig, which is blazing a trail for the city’s booming food scene, says: “With so many people from around the globe coming to Berlin, they bring different cultures, identities, habits and, of course, money.” He says the local dining scene is being influenced by cuisines from around the world with Asian elements mixed in, “which makes it interesting”.

Spurred by a booming tech industry and, according to “Global Startup Ecosystem Ranking 2015”, the fastest growing start-up ecosystem globally, young and talented professionals are flocking to this post-war Bohemian culture capital, attracted as much by its economic and political prowess as they are by its comparatively affordable housing. Berlin has been held up among contenders to profit from London’s expected demise as the leading financial centre in Europe once Britain leaves the European Union. That’s not to mention industry chatter about Berlin staking its claim as a potential epicentre of European fintech.

“The new economy of the city means that there are more people, in particular more open-minded people, who can support exciting new food business,” says Dylan Watson-Brawn, the Canadian chef and co-owner of one of the city’s newest and foremost cutting-edge eateries, Ernst.

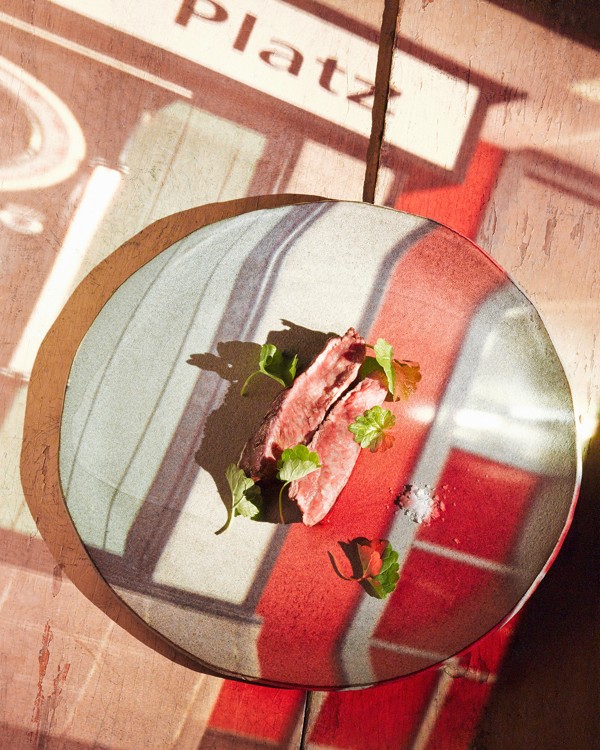

Watson-Brawn adds that newer restaurants are moving away from the traditional French style that dominated gastronomy in Germany over the past decades. His restaurant sources vegetables from organic/biodynamic farms in the region, meats from farms that practise ethical raising and slaughtering, and seafood from sustainable fishermen. “Chefs are taking more risks, although things are still far behind cities like London and Paris,” he says.

Other cities are years behind the quality and innovation we see in Berlin

This obsession with local artisan produce may be a relatively recent development in Berlin, but 230 kilometres away in Wolfsburg, Sven Elverfeld, executive chef of Aqua Restaurant at The Ritz-Carlton Wolfsburg, started working with seasonal produce and local suppliers back in 2000.

“In the region, we get very good white asparagus, and from Lüneburger Heide, we get a high-quality trout,” Elverfeld says. “From Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, we get nice dry aged calf, and from the Müritz [near Berlin] we get excellent lamb, which we use to work with lamb sweetbread and tongue.” Elverfeld also works with a regional hunter who supplies him with deer and venison, and several local farmers who specialise in the production of wild herbs and micro vegetables.

Smaller, more casual restaurants are also getting onto the bandwagon.

“Diners are now more interested in the process of production and food in general,” says Andreas Rieger, chef de cuisine of the one Michelin-starred Einsunternull. “The usage of luxury products like foie gras, caviar and truffle has decreased. Instead, we search for quality and have a close cooperation with farmers and producers.” In his restaurant in Berlin, 90 per cent of the produce is from Germany and, during the recent summer, staff of Einsunternull helped in the harvest of asparagus at farmer Paul Schulze’s property.

“We even started a Facebook call searching for volunteers who could help pick the asparagus,” Rieger says. “As a reward, helpers got a five-course lunch voucher with paired drinks at our restaurant.”

Meurling of 12forward says that it was virtually impossible to have casual fine dining in Berlin more than three years ago, referring to eateries like Ernst, Nobelhart & Schmutzig and Einsunternull. “But the city’s ‘bistrofication’ in recent years means that it now has a solid offering of restaurants with fine dining background cooking simple yet advance fare in casual surrounds.”

He adds that the broad cultural diversity in the population and the boom in contemporary street food in 2013 has also led to interesting offerings in markets like Street Food Thursday and Bite Club. He also notes a surge in contemporary “ethnic projects like Vietnamese and Korean”.

Perhaps it helps that most chefs populating the growth of alternative cuisines are not natives of Berlin – Lode & Stijn is run by Lode van Zuylen and Stijn Remi from Holland; Ernst by Dylan Watson-Brawn from Canada; and Dóttir by Victoria Eliasdóttir from Iceland.

“Even the German chefs in Berlin, like Micha Schäfer from Nobelhart & Schmutzig and Sebastian Frank from Horváth, are pretty much from other places in Germany,” Meurling adds.

For a snapshot of how far Berlin has progressed as a dining city, Tim Raue, a Berlin native and chef-owner of the eponymous Asian-inflected restaurant, suggests we look at the Michelin Guide.

“In the last 10 years, Berlin went from about 10 Michelin starred restaurants to 25,” says Raue, who was once hailed as one of the chefs responsible for making Berlin an exciting food city in Germany.

“Apart from having better quality restaurants, young chefs are seeking and creating their own culinary style – that to me is the most important development in our dining scene.”

And for avid diners, there is no lack of restaurant options in Berlin, be it minimalist produce-driven bistro cuisine or multi-Michelin-starred Asian- or French-inflected fine dining.

New restaurants, foreign chefs and a booming tech industry has taken Berlin from 10 Michelin starred restaurants to 25 in the last decade