Animal rights activists want Nepal's sacrifice festival stopped

Hundreds of thousands of livestock were killed in the last Gadhimai festival in Nepal, which rights campaigners dubbed a bloodbath

The Gadhimai temple in southern Nepal is preparing to celebrate its quinquennial festival in which thousands of animals are sacrificed to please the Hindu goddess of power.

Organisers estimate up to 15,000 buffalo will be slaughtered on November 28-29, the only two days allotted for animal sacrifice during the month-long festival. It is considered to be the world's largest ritual animal slaughter.

During the 2009 festival, more than 250,000 animals and livestock including buffalo, goats, pigs, rats, chicken, ducks and pigeons were killed around the 5km radius of the temple in the village of Bariyapur, 145km from capital Kathmandu.

"It was like a bloodbath," said Manoj Gautam, president of the Animal Welfare Network Nepal, who visited the site. "The mass slaughter of animals at Gadhimai represents violence in an extricable, inhumane manner and we are trying to stop that."

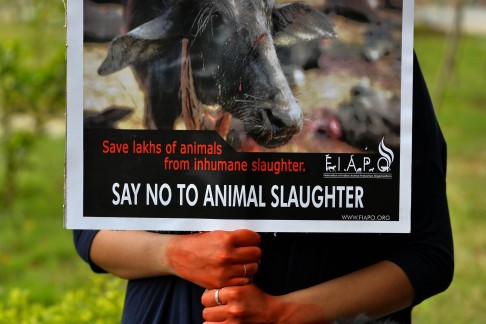

Animal rights organisations are campaigning to change this centuries-old tradition, but it is an uphill battle.

In remote parts of Nepal and neighbouring Indian states from where the majority of devotees visit Gadhimai, activists say religious beliefs are entrenched in the community. People refrain from challenging these customs fearing negative consequences from an angry goddess.

Gadhimai's head priest, Mangal Chaudhary Tharu, said the tradition could not be changed overnight.

The more than 250-year-old festival started with the village's feudal landlord, Tharu said. While in prison, he had a dream that a mass slaughter to appease the goddess would resolve his problems. "People come here with strong belief," Tharu said. "They sacrifice animals to thank the goddess for fulfilling their wishes. But we don't ask or force them to do that - it's their own will. These days some people also bring sweets and break coconuts as a symbolic sacrifice."

After gruesome images from the previous festival surfaced, online petitions pleading with the Nepalese government to end this carnage have gained momentum, some even calling for a boycott of Nepal as a tourism destination until it stops.

British actress Joanna Lumley and Indian animal rights activist Maneka Gandhi have opposed sacrifices at Gadhimai.

"I would appeal to the Nepal government to stop this terrible massacre; it has absolutely no religious connotation," Gandhi said.

Earlier this month, protesters outside the Nepalese Embassy in London and New Delhi demanded an end to the practise.

But Nepal's official response to this culturally complex issue has been muted.

"It will be difficult to immediately stop the ancient tradition, but we are not in the process of promoting such practise," said Mohan Krishna Sapkota, spokesperson for the Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation.

India, with which the country shares close cultural ties, has already banned animal sacrifices in many of its temples.

Considering the large number of devotees likely to take animals across the border to Gadhimai, the Ministry of Home Affairs' Border Management Division has put border outposts in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh on high alert.

India's Supreme Court recently issued an order to "ensure that no live cattle and buffaloes are exported out of India into Nepal, but under licence."

Meanwhile, public health experts are urging the Nepalese government to remain vigilant of possible outbreaks of diseases likely to be passed from animals to humans.

"There are risks of many infectious and communicable diseases," said Dr Yashovardhan Pradhan, former director general of the Department of Health Services. "It's difficult to change people's cultural beliefs but [ritual sacrifices] need to be done in a safe manner."

Nepal's Directorate of Animal Health plans to establish inspection posts around the festival site to check the health and well-being of animals, said Umesh Dahal, senior veterinary officer overlooking festival operations.

According to its action plan, the department will also vaccinate animals and livestock in and around surrounding villages and ensure there are proper disposal pits for animal carcasses.

But activists like Gautam claim that the government is not doing enough; the scale of such mass slaughter is unjustifiable.

"The entire world [will be] watching," Gautam said. "This could tarnish Nepal's image internationally."