Short of war, US can’t help but lose to China’s rise in Asia, says think tank Lowy Institute

- Lowy Institute’s 2019 Asia Power Index puts Washington behind both Beijing and Tokyo for diplomatic influence

- Trump’s assault on trade has done little to stop Washington’s decline in regional influence, compared to Beijing, say experts

The United States may be a dominant military force in Asia for now but short of going to war, it will be unable to stop its economic and diplomatic clout from declining relative to China’s power.

That’s the view of Australian think tank the Lowy Institute, which on Tuesday evening released its 2019 index on the distribution of power in Asia.

However, the institute also said China faced its own obstacles in the region, and that its ambitions would be constrained by a lack of trust from its neighbours.

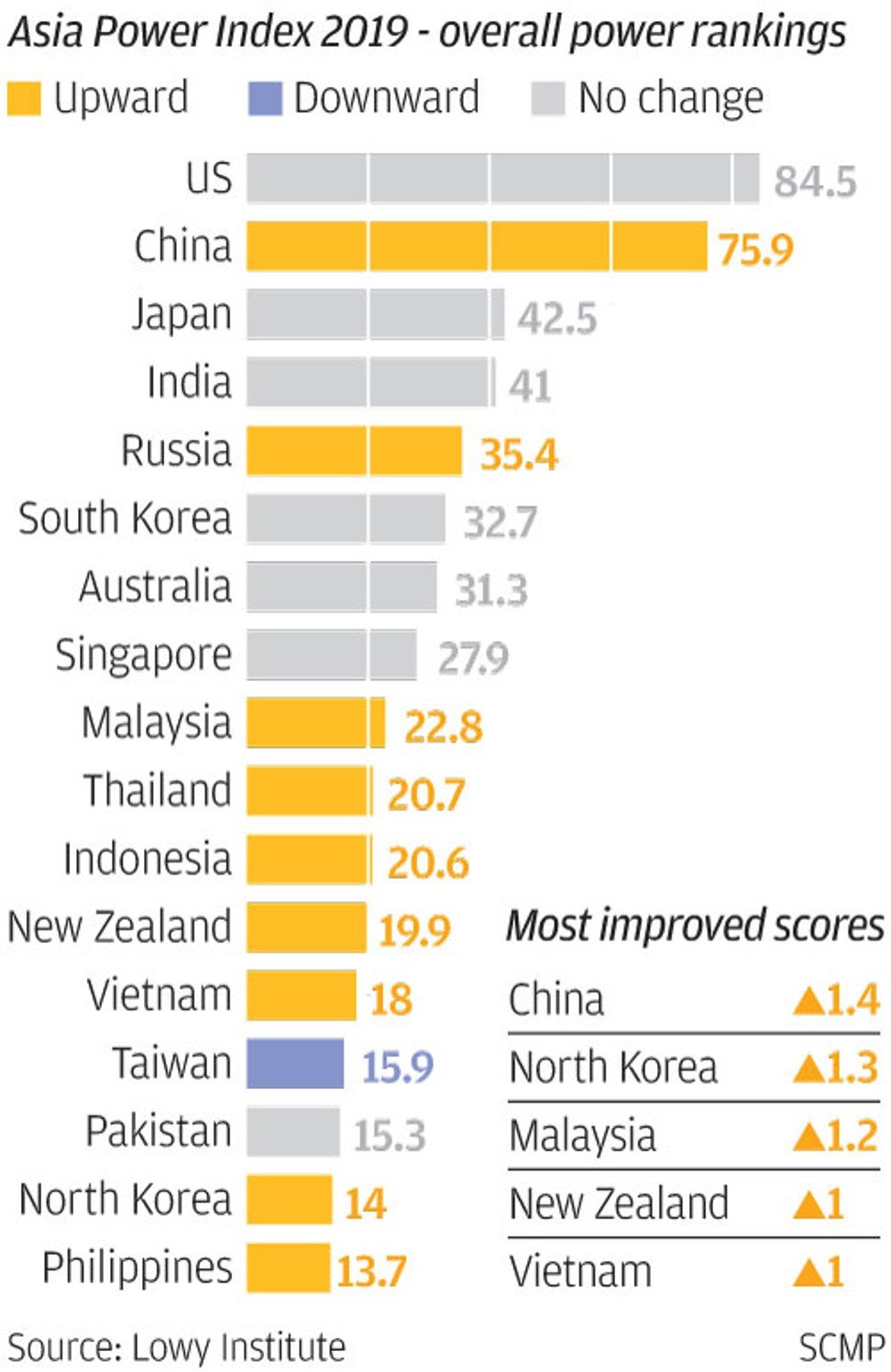

The index scored China 75.9 out of 100, just behind the US, on 84.5. The gap was less than America’s 10 point lead last year, when the index was released for the first time.

“Current US foreign policy may be accelerating this trend,” said the institute, which contended that “under most scenarios, short of war, the United States is unlikely to halt the narrowing power differential between itself and China”.

Since July, US President Donald Trump has slapped tariffs on Chinese imports to reduce his country’s trade deficit with China. He most recently hiked a 10 per cent levy on US$200 billion worth of Chinese goods to 25 per cent and has also threatened to impose tariffs on other trading partners such as the European Union and Japan.

Herve Lemahieu, the director of the Lowy Institute’s Asian Power and Diplomacy programme, said: “The Trump administration’s focus on trade wars and balancing trade flows one country at a time has done little to reverse the relative decline of the United States, and carries significant collateral risk for third countries, including key allies of the United States.”

The index rates a nation’s power – which it defines as the ability to direct or influence choices of both state and non-state actors – using eight criteria. These include a country’s defence networks, economic relationships, future resources and military capability.

It ranked Washington behind both Beijing and Tokyo in terms of diplomatic influence in Asia, due in part to “contradictions” between its recent economic agenda and its traditional role of offering consensus-based leadership.

Toshihiro Nakayama, a fellow at the Wilson Centre in Washington, said the US had become its own enemy in terms of influence.

“I don’t see the US being overwhelmed by China in terms of sheer power,” said Nakayama. “It’s whether America is willing to maintain its internationalist outlook.”

But John Lee, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, said the Trump administration’s willingness to challenge the status quo on issues like trade could ultimately boost US standing in Asia.

“The current administration is disruptive but has earned respect for taking on difficult challenges which are of high regional concern but were largely ignored by the Obama administration – North Korea’s illegal weapons and China’s predatory economic policies to name two,” said Lee.

“One’s diplomatic standing is not just about being ‘liked’ or ‘uncontroversial’ but being seen as a constructive presence.”

CHINA’S RISE

China’s move up the index overall – from 74.5 last year to 75.9 this year – was partly due to it overtaking the US on the criteria of “economic resources”, which encompasses GDP size, international leverage and technology.

China’s economy grew by more than the size of Australia’s GDP in 2018, the report noted, arguing that its growing base of upper-middle class consumers would blunt the impact of US efforts to restrict Chinese tech firms in Western markets.

“In midstream products such as smartphones and with regard to developing country markets, Chinese tech companies can still be competitive and profitable due to their economies of scale and price competitiveness,” said Jingdong Yuan, an associate professor at the China Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

“However, to become a true superpower in the tech sector and dominate the global market remains a steep climb for China, and the Trump administration is making it all the more difficult.”

The future competitiveness of Beijing’s military, currently a distant second to Washington’s, will depend on long-term political will, according to the report, which noted that China already spends over 50 per cent more on defence than the 10 Asean economies, India and Japan combined.

TRUST ISSUE

However, distrust of China stands in the way of its primacy in Asia, according to the index, which noted Beijing’s unresolved territorial and historical disputes with 11 neighbouring countries and “growing degrees of opposition” to its signature Belt and Road Initiative.

Beijing is locked in disputes in the South China Sea with a raft of countries including Vietnam, the Philippines and Brunei, and has been forced to renegotiate infrastructure projects in Malaysia and Myanmar due to concerns over feasibility and cost.

Xin Qiang, a professor at the Centre for American Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai, said Beijing still needed to persuade its neighbours it could be a “constructive, instead of a detrimental, force for the region”.

“There are still many challenges for [China to increase its] power and influence in the Asia-Pacific,” Xin said.

Wu Xinbo, also at Fudan University’s Centre for American Studies, said Beijing was having mixed success in terms of winning regional friends and allies.

“For China, the key challenge is how to manage the maritime disputes with its neighbours,” said Wu. “I don’t think there is growing opposition to the Belt and Road Initiative from the region, actually more and more countries are jumping aboard. It is the US that is intensifying its opposition to the project as Washington worries it may promote China’s geopolitical influence.”

Yuan said the rivalry between the US and China would persist and shape the global order into the distant future.

“They can still and do wish to cooperate where both find it mutually beneficial, but I think the more important task for now and for some time to come, is to manage their disputes in ways that do not escalate to a dangerous level,” Yuan said. “These differences probably cannot be resolved given their divergent interests, perspectives, etc, but they can and should be managed, simply because their issues are not confined to the bilateral [relationship] but have enormous regional and global implications.”

Elsewhere in Asia, the report spotlighted Japan, ranked third in the index, as the leader of the liberal order in Asia, and fourth-placed India as an “underachiever relative to both its size and potential”.

Lee said the index supported a growing perception that Tokyo had emerged as a “political and strategic leader among democracies in Asia” under Shinzo Abe.

“This is important because Prime Minister Abe wants Japan to emerge as a constructive strategic player in the Indo-Pacific and high diplomatic standing is important to that end,” Lee said.

Russia, South Korea, Australia, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand rounded out the top-10 most powerful countries, in that order. Among the pack, Russia, Malaysia and Thailand stood out as nations that improved their standing from the previous year.

Taiwan, ranked 14th, was the only place to record an overall decline in score, reflecting its waning diplomatic influence after losing three of its few remaining diplomatic allies during the past year.