North Korean refugees fear time has run out for family reunions despite Kim-Trump summit

- There are about 60,000 South Koreans who have applied for reunions but were refused, and their time is running out

When Lee Geum-soon left her two-year-old daughter with her in-laws in North Korea and followed retreating US and South Korean troops across the border in 1951, she believed they would be reunited in a matter of days.

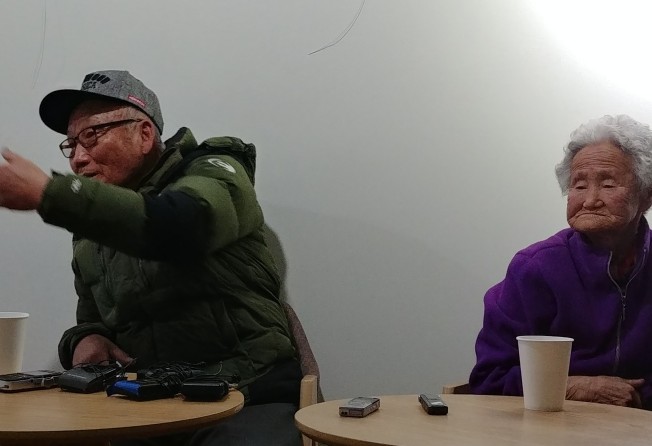

Seven decades later, the 93-year-old has given up hope of ever seeing her youngest child again even though warming ties between the North and South have raised hopes both sides, still technically at war, could agree a peace treaty.

Seoul recently stopped referring to Pyongyang as its enemy in a policy paper. North Korean leader Kim Jong-un has sought rapprochement with the South and the US in the past year. He is scheduled to meet US President Donald Trump in Hanoi at the end of the month as Washington seeks to persuade Pyongyang to give up nuclear weapons.

“I miss my youngest daughter. But I don’t think I will be able to see her again,” she said.

Millions of Koreans were separated by the division of the Korean peninsula in 1948 into the communist North and the capitalist South and the Korean war of 1950-53.

After the inter-Korean summit in 2000, the two countries arranged reunions of separated families. Some 4,000 people met with 20,000 relatives living on the other side the border. However, there are another 60,000 South Koreans who have applied for reunions but were not granted the opportunity.

Both Lee and her friend Kim Sung-ho gave up applying for their own reunions with their relatives in the North after from other North Korean refugees who already applied but failed to be chosen.

“They told me we would have no chance either as we are considered as traitors by North Koreans,” Kim said.

I miss my youngest daughter. But I don’t think I will be able to see her again

Lee fled the North with her husband and two older daughters. They settled in Sokcho, a port city near the border, about 158km northeast of Seoul.

Hundreds of other North Korean refugees from her hometown – Bukchong County in the northern province of Hamgyong – have also made homes there.

Lee and her husband had to do “whatever we could do” to feed their two other daughters they took with them to the South – doing chores, begging food or even picking through food waste left by US soldiers.

“Now, Sokcho is my hometown,” she said. “It’s been too long a time that we’ve been separated from each other and I have no desire to go back to the North. No more.”

Kim Sang-ho, Lee’s friend from her home town, recalled the years after heading south.

“We had extremely hard times living as war refugees as the Southerners looked down on us and harassed us. We missed our hometown so much that we gathered here in Sokcho to stay near home as much as possible,” Kim, 77, said.

Kim and his parents sailed to the South between late 1950 and early 1951 on their rickety fishing boat, just as the allied forces who advanced deep into the North were pulling back after being overwhelmed by a Chinese counteroffensive.

About 100,000 troops and 100,000 civilians, including the future parents of South Korean President Moon Jae-in, were evacuated from the port of Hungnam in an operation known as the “Christmas miracle”.

Kim Sang-ho’s family followed the changing front lines before settling in the spontaneously built refugee camp, which has become known as “Abai” village, a Hamgyong province dialect meaning “old people” as most of the settlers there have become old.

“The thickly wooded beach was incredibly beautiful,” he said. “We built hakoban [shacks] with whatever materials we could get our hands on – pieces of wood for doors, corrugated iron slates for the roof, pieces of wood crates for windows – and called it home.”

Kim saw some adult refugees ruin their health, drinking heavily and tortured by their longing for the families they left behind in the North.

Nonetheless, the Abai village has become a tourist attraction thanks to its history and North Korean culinary culture, including the popular Abai Sundae, a North Korean sausage filled with a mixture of ground vegetables, pork meat and curdled pork blood. A peculiar liquor called Bultokju (erection liquor), brewed with various herbs and sold in a bottle with a penis-shaped lid, is also popular among tourists.

When reunions of separated families were first arranged following an inter-Korean summit in 2000, many North Korean refugees were afraid to apply for reunions, concerned their relatives in the North would be relegated to an unfavourable social position if authorities knew their families fled south.

I am not an expert but I think we have to be very careful when we talk with them

Even so, some of them applied for reunions but few received confirmations from the North, as the refugees are considered “traitors”, Kim said.

In contrast, many South Koreans who joined the North’s side during the war were able to see their relatives they left in the South.

Kim and Lee both gave up applying for reunions with their families in the North. However, Lee and her husband were among the first South Koreans to board a cruise ship bound for the North’s scenic Mount Kumgang after cross-border tours began in 1998 under the policy of engagement and reconciliation with the North.

Lee’s husband brought several wrist watches as gifts for North Koreans but he was refused as such an act is considered politically motivated in the North and constitutes a breach of regulations for South Korean tourists visiting the North.

Regarding the Kim-Trump summit scheduled for February 27-28 in Vietnam, Kim said he is still sceptical of North Korea’s intentions after spending three years in primary school, “with the portraits of Stalin and the North’s founder Kim Il-sung staring down on us” from the classroom wall.

He said: “Who in the world would not want peace? I am not an expert but I think we have to be very careful when we talk with them as you never know what they have in their deep mind.”