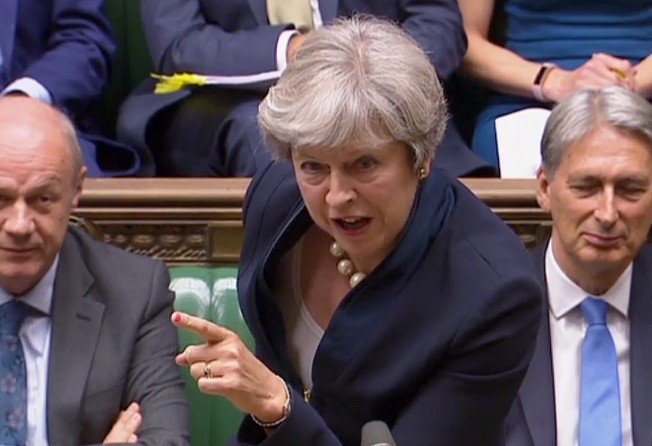

Theresa May’s Brexit battle returns to parliament as legislation faces opposition from both sides of political divide

Negotiations with the EU on the terms of the divorce are progressing slowly, threatening Britain’s hopes to move on to talks on a future trade relationship within weeks

British lawmakers began debating on Thursday a landmark bill to end Britain’s membership of the European Union, with Prime Minister Theresa May gearing up for a major battle.

The bill provides for the repeal on Brexit day of the 1972 European Communities Act that conferred Britain’s membership, and also converts estimated 12,000 existing European regulations into British law.

Ministers claim it is the first step in implementing last year’s referendum vote for Brexit, and will provide legal continuity to ensure no “cliff-edge” when Britain leaves the bloc in March 2019. But critics warned it represents an unprecedented “power-grab” by giving the government broad powers to amend the EU laws as they are transferred without proper parliamentary scrutiny.

A House of Lords committee said it “weaves a tapestry of delegated powers that are breathtaking in terms of both their scope and potency”, and the opposition Labour party has vowed to vote against it.

May’s Conservative party lost its majority in the House of Commons in a snap election in June, but her alliance with Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party means the first stage of the bill should pass.

However, she is vulnerable to rebellions on her own side as the legislation comes under detailed scrutiny in the coming weeks, while at least seven more Brexit-related bills are expected before Britain leaves the EU.

Cabinet divisions over one of the most contentious issues of Brexit, immigration, emerged this week following the publication of a leaked report proposing restrictions on EU workers once Britain ends free movement of labour.

Interior minister Amber Rudd was said by several newspapers to be unhappy with the plans, which have been condemned by several business groups as too tough.

Meanwhile in Brussels, negotiations with the EU on the terms of the divorce are progressing slowly, threatening Britain’s hopes to move on to talks on a future trade relationship within weeks.

May said on Thursday that the Repeal bill was “the single most important step we can take to prevent a cliff-edge for people and businesses, because it provides legal certainty” after Brexit.

Officials estimate that around 800 to 1,000 amendments will be needed to the EU laws being transferred – a task too large to involve full parliamentary scrutiny in each case, which is why they want to use the special powers.

The powers would expire two years after Brexit and cannot be used to raise taxes or amend human rights law – but they could be used to implement parts of the final Brexit deal agreed with Brussels.

Labour has said it would seek to defeat the bill when, after two days of debate, it goes to its first vote in the House of Commons on Monday.

“If this is passed in its current form, MPs are effectively relegating themselves to spectators as the baton is passed to the government to do as it likes with Brexit,” Brexit spokesman Keir Starmer told BBC radio.

The Scottish National Party (SNP) and the smaller Liberal Democrats party, which are both pro-European, are also likely to vote against the bill.

With the DUP’s support, the government has a working majority of 13 MPs in the House of Commons and the first stage of the Repeal Bill should pass.

But Conservative MPs are likely to join opposition parties in trying to amend the legislation when it moves to the next stage of debate later this autumn.

The devolved institutions in Scotland and Wales could also seek to hinder the progress of the bill.

All the EU powers being transferred will initially be taken back by the Westminster parliament, even where they involve policy areas that have been devolved to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The government has promised discussion on devolving these powers but the semi-autonomous administrations are sceptical they will really do so.