Malaysia could play a ‘vital role’ in mediating the conflict between Thailand’s army and Muslim separatists – but will the junta allow it?

- Over the past 15 years, a violent conflict in Thailand’s southernmost provinces has claimed more than 7,000 lives

- But analysts are hopeful that neighbouring Malaysia can help the country achieve a resolution to the war between the insurgents and the army

Peace talks to end a 15-year war in Thailand’s southernmost provinces between Muslim guerilla fighters and the army hit a snag last weekend, when Bangkok’s new peace negotiator did not turn up for a scheduled meeting.

But analysts are still hopeful that a resolution to the long-running insurgency is in sight – and they are pinning their hope on Malaysia’s role in the talks.

After he returned to power last year, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed expressed his commitment to the peace process and appointed former police chief Abdul Rahim Noor – who played a role in ending the country’s communist insurgency in 1989 – as representative in the Thai peace talks.

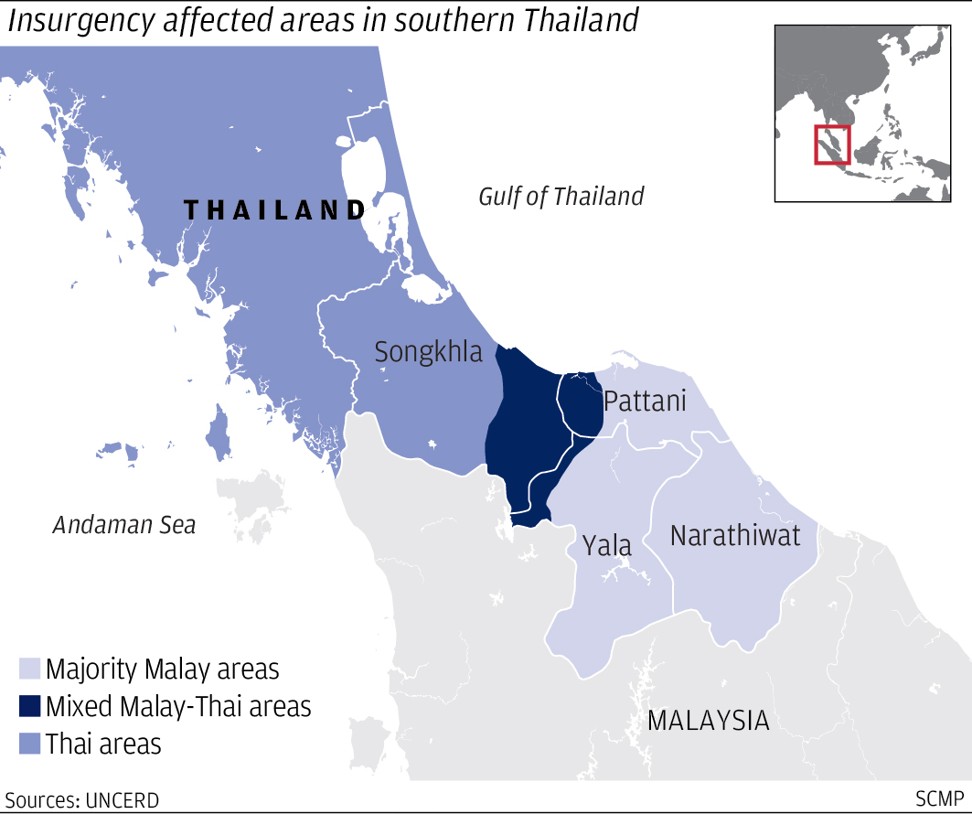

The war affects a region that spans the Thai provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat and Yala – as well as Songkhla to a lesser extent.

It was an independent Muslim sultanate that was formally annexed by Buddhist-majority Thailand at the turn of the 20th century. In 2004, simmering ethnic tensions escalated into full-blown conflict as a result of long-running centralisation policies, local administrative changes and a war on drugs that hit the region particularly hard.

More than 7,000 people have died in the violence over the past 15 years, according to local monitoring organisation Deep South Watch.

Paul Chambers, a lecturer at Naresuan University in northern Thailand, said given Malaysia’s proximity to the conflict zone and the fact that most Thai Muslims in the southern provinces are ethnic Malays, Malaysia could “play a vital role” in ending the conflict.

Zachary Abuza, a professor specialising in Southeast Asian security issues at the National War College in Washington DC, said the Malaysian government is interested in the peace talks because “they don’t want instabilities on their borders”.

Malaysia as mediator can release a message to the groups

Malaysians would also be concerned about the flow of weapons from Thailand towards the south after several Islamic State cells were dismantled in Malaysia last year, even if “there is no evidence that IS is involved in the deep south”, said Abuza.

However, the Thai efforts in peace talks have “never been in good faith”, said Abuza, pointing to negotiator Udomchai Thammasarorat’s snub of a meeting facilitated by Malaysia with the delegation of the Mara Patani, an umbrella organisation consisting of several separatist groups. Udomchai only showed interest in meeting its leader Sukree Haree.

After the incident, Mara Patani suspended the talks until after Thailand’s March 24 elections and asked for the Thai facilitator to be replaced with a person “with more credibility”.

“Mara Patani sees the attitude of refusal to confront the dialogue team as unacceptable and [we] suspect a hidden agenda when he only wanted to meet me,” Sukree Haree told Malaysian news agency Bernama.

The latest round of peace talks had just officially begun on January 4.

Abuza said Thailand’s junta government, which seized power in May 2014, would not give Malaysia any substantial role in negotiations. “They are terrified that this [would] become an internationalised conflict.”

Chambers said the junta saw the talks as a “public relations ploy”.

“It is trying to show itself to be a peacemaker, but at the same time, it has increased the level of violence [in the southern provinces],” he said.

Rungrawee Chalermsripinyorat, an independent researcher and former analyst for the International Crisis Group NGO, is hopeful that last year’s change of government in Malaysia, and the appointment of new negotiators for both sides, could yet prove to be “major developments” that “change the direction of the peace dialogue”.

“It is not a completely new track, but it seems to be a significant change in many respects,” she said.

She also considers that the Thai government has made “good efforts” to invite everyone to the table.

Last month, Udomchai – considered a moderate within the army – told a press conference that the junta had taken Malaysia’s advice and was open to discussing some degree of autonomy for the region, marking a change from previous talks, according to Rungrawee.

He also opened the door for all separatist groups, including “those that use violence”, to engage in the process, which has been interpreted as an olive branch to the Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) – an extremist militant group that has shunned negotiation efforts in the past.

“This is a very positive change,” Rungrawee said. “They are trying to send a positive gesture to try to convince the BRN to come to the table.”

Srisompob Jitpiromsri, who runs the Pattani-based Deep South Watch, also viewed the developments as positive.

“Now the Thai government seems to be more open on the autonomy choice. That is a positive side that Malaysia as mediator can release as a message to the groups,” he said.

But both the involvement of Kuala Lumpur and the upcoming Thai elections could also destabilise the peace process.

“Some insurgent groups living in Malaysia have negative feelings towards Malaysia ... because they have been arrested and sent to Thai authorities in the past,” Srisompob said.

These groups have requested the participation of other international observers, but Thai authorities have rejected the idea “because it would mean the internationalisation of the conflict”, he said.

The future of the peace process will remain unclear “until the new [Thai] government is formed”, Rungrawee said.

“If the pro-democracy camp wins, we are likely to see a revision of the dialogue team again. But, if the pro-junta camp wins, the peace talks might just be a continuation of the current process.”