Duterte looks to Philippines’ private sector to reboot signature building plan

- By the time he steps down in 2022, the Philippine president wants work to have begun on 100 priority projects under his ‘build, build, build’ programme

- Nearly half of these will now be funded by investments from companies like oil and shipping giant Udenna and regional beer behemoth San Miguel

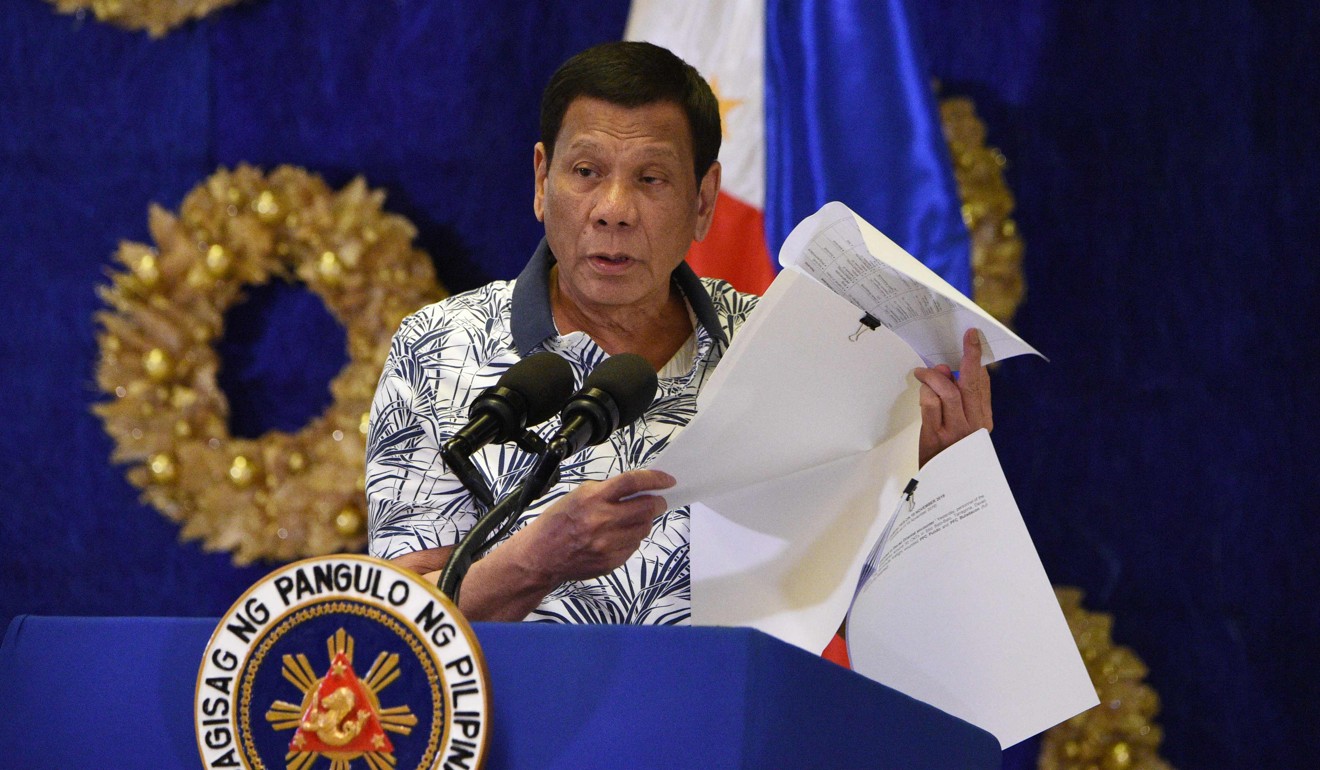

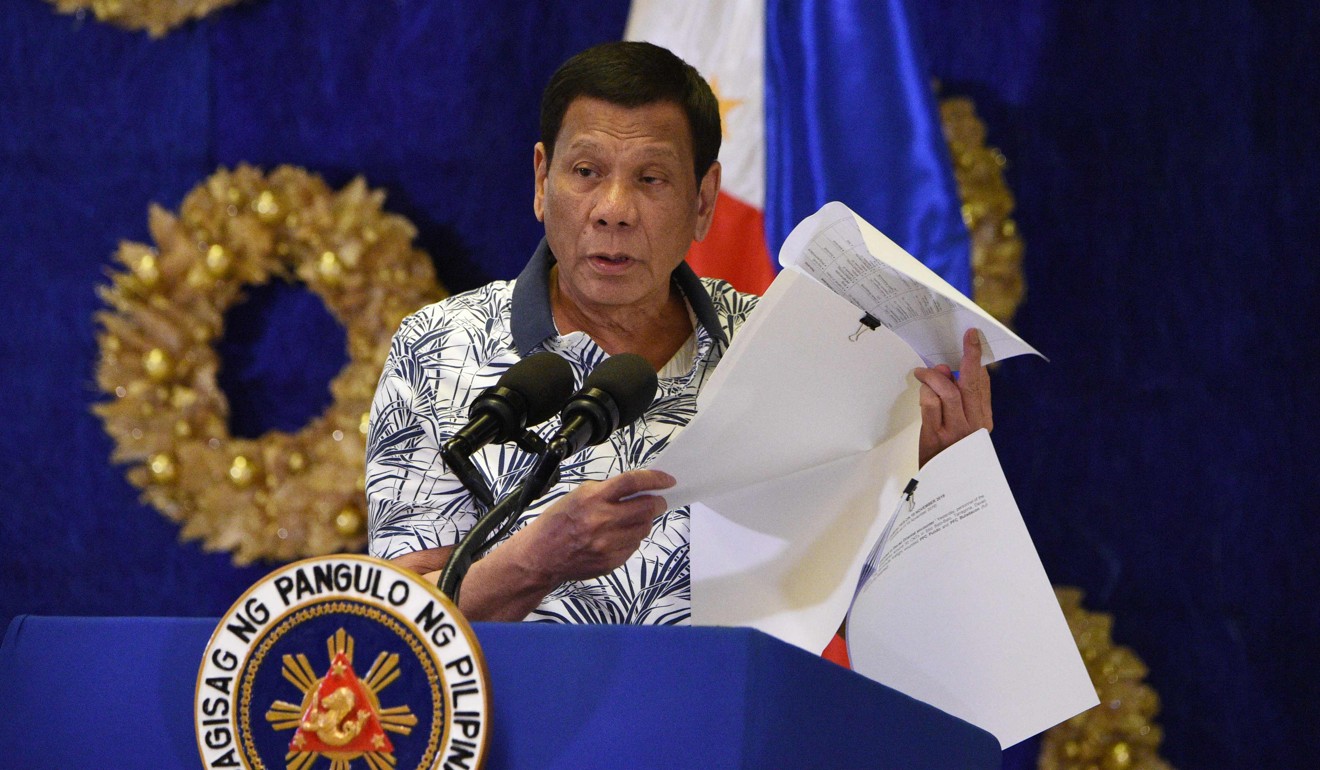

When Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte took office in 2016, he promised US$165 billion in spending to “build, build, build” roads and railways in the Southeast Asian nation.

The programme consisted of 75 key projects – including a railway stretching the length of Luzon, the country’s main island – along with thousands of smaller ones like schools, to be funded mostly from development loans and the government’s budget.

Halfway through the president’s six-year term, only two of those key projects have been completed. Most have run into bureaucratic delays, or faced problems like acquiring land and financing to get off the ground.

Now Duterte is revamping the plan and giving businesses a bigger share of the projects, after earlier shying away from privately led projects because of financing risks and delays. That is a boon for companies like Megawide Construction, which is already planning bids for rail and other infrastructure projects.

“It’s a good opportunity for us,” said Edgar Saavedra, CEO of Megawide. “This is like a rebirth for the Philippines.”

Duterte’s new plan consists of 100 priority projects, nearly half of which will be funded from investments by companies like San Miguel, which wants to build a 736-billion peso (US$14.5 billion) airport north of Manila, and Udenna, which proposed a monorail in Cebu.

The revamp could result in a more streamlined approval process, given “sufficient attention to fast-track implementation”, according to Cosette Canilao, chief operating officer at Aboitiz Equity Ventures’ infrastructure unit. Canilao was head of the country’s Public-Private Partnership Centre, which reviewed company-led infrastructure projects under Duterte’s predecessor, Benigno Aquino.

The infrastructure gap is large across emerging Asia, with the Asian Development Bank estimating the region needs US$26 trillion worth of investment through to 2030 to address bottlenecks and keep growth going. Political uncertainty has delayed infrastructure projects in Thailand, while in Indonesia, the government has offered tax benefits to get around funding constraints.

Philippine billionaire Enrique Razon, chairman of port operator International Container Terminal Services, said he is looking at proposing more infrastructure projects to the government. Razon is a major shareholder in a venture that seeks to develop a new water source for the Philippine capital.

The government aims to start construction on all 100 projects on the new list before Duterte steps down in 2022, with one-third of the projects expected to break ground next year, said Vince Dizon, a presidential adviser on the infrastructure programme, who was appointed to the post in September.

Private-sector participation alone does not guarantee projects will get completed. Reforms are needed to speed up approvals, address corruption and prevent policy reversals, said James Su, an infrastructure analyst at Fitch Solutions in Singapore.

The scope of Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” programme is so large that “it was always going to be a challenge to implement the initiative in full,” he said.

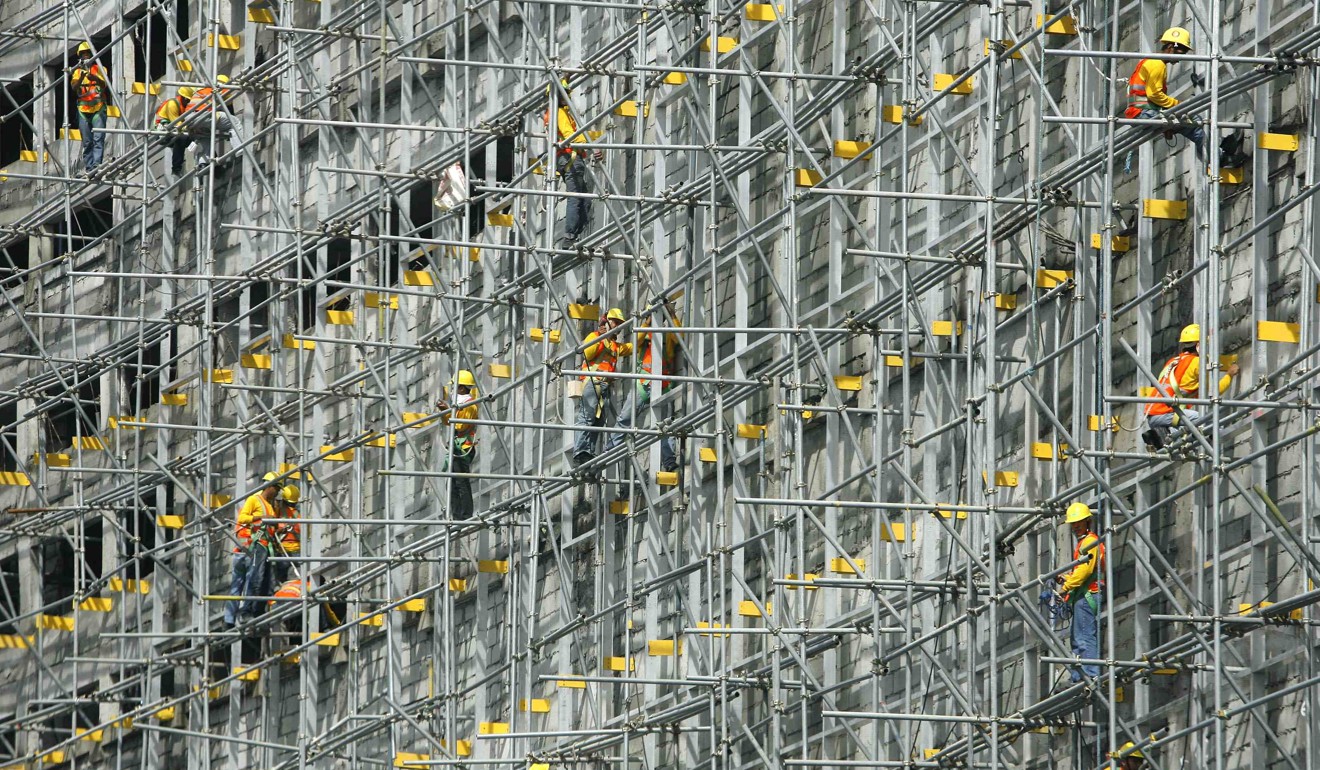

Turning to companies also poses risk a of competing firms suing each other over contracts. And even when projects do get off the ground, the Philippines faces a shortage of construction workers.

“These are issues all countries face when they raise infrastructure,” Thomas Helbling, the head of the International Monetary Fund’s mission to the Philippines, said at a recent conference in Manila.

Speaking to foreign investors this month at the Clark Freeport special economic zone, Antonio Lambino, an assistant secretary in the Finance Ministry, said the country’s infrastructure drive goes beyond the list of high-profile projects. Public infrastructure spending made up a record 5 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product last year, and should rise to 7 per cent by 2022, he said.

“We go around to take a look at these projects on the ground, and we do see that ‘Build, Build, Build’ is making a difference in people’s lives,” Lambino said.