China backs niche films about minority groups in hope of easing ethnic tensions

In the upcoming film Deegide, a Mongolian woman herder struggles to keep her family and their sheep alive as a spring snowstorm descends upon the plains, threatening them with starvation. She gets no help from her husband, a depressive alcoholic who is lost without the horses and lush meadows his father knew.

The film explores the will to life against a nature that is both the sole provider and the greatest danger to survival. The film closes with the titular Deegide taking her husband, who has fallen ill, to a hospital in Beijing. The treatment will bankrupt the family, but as she embarks on the journey, Deegide shows not defeat but tested resolve.

What makes the film unusual from the hundreds of others released on the mainland every year is its backers, the State Ethnic Affairs Commission. Deegide is the first in a series the commission hopes to make about China’s 55 ethnic minority groups that co-exist, not always easily, with the Han majority.

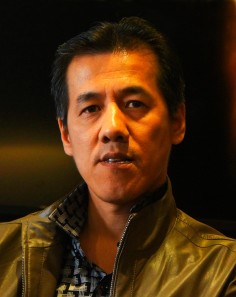

The films would not be an empty exercise in propaganda nor a broadside against separatist movements, said Zhang Zhiqiang, the head of the project’s management committee.

While international viewers may be interested in stories set on the plains of Gansu, or the dusty backstreets of Hotan, luring Han to cinemas at home might prove more difficult.

Zhang said they had already attracted 300 million yuan (HK$379 million) in private funding, and predicted at least 2 billion could be raised by the end of next year. They planned to release at least two films every year, with a goal of covering all 55 groups within a decade. All the films will have a guaranteed first run at 48 leading cinemas across the country.

Ethnic minorities cautioned the scripts should be written by locals. “I would love to watch films featuring the history of Tibet ,” said Dhnath Drolma, a Tibetan jewellery store owner in Chengdu in Sichuan province.

“I hate the idea of labelling us a primitive and distant ethnic group with odd customs simply to attract audience overseas in a novelty bid. I want to see a movie telling a true story of a Tibetan tusi or chieftain a few hundreds of years ago … Such a film would help preserve and record our root and culture,” she said.

Pointing to Deegide, Zhang said the film was a sincere attempt to show the strengths of the Mongolian people and their respect for nature. It doesn’t shy away from the impact of modernisation on the nomads, and acknowledges that many of the men in the communities have lost the roots of their identity. But the films would steer clear of any political messages, he said.

“Our goal is to spread the truth … and virtues about China’s ethnic minority groups,” Zhang said. “In the movies, the audience won’t see well-made plots serving a propaganda attempt at ethnic solidarity or against separatism.”

The films had to be commercially viable, and a large part of the formula would rely on drawing audiences overseas, Zhang said.

“For example, the Story of the Weeping Camel, a Mongolian-themed movie [debuting in 2003] was made for just 4 million yuan but earned 40 million euros overseas … its success proves foreign markets should be main focus for our ethnic-themed films.”

However, some scholars and experts on ethnic issues questioned whether the films could lure moviegoers in the mainland’s cities.

Such films proved popular in the years after the 1949 civil war and following the breakout of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. But they have mostly distinguished themselves as box office flops in the past 20 years, according to Yu Ji, a professor of communication at Southwest University in Chengdu .

“Since the 1980s, more than 200 ethnic-themed films have been produced. But only a few have been released in theatres. It shows that mainland audiences in the big cities now feel distant from ethnic minorities.”

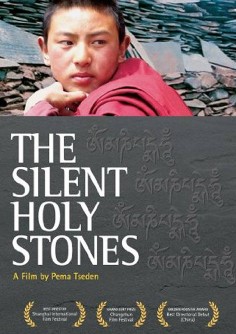

The film knits drama and comedy to tell the story of a young Buddhist monk who returns home from the monastery for a two-day visit, and grows entranced with a programme showing on his parents’ television set. He returns to the monastery and together with a boy trulku, or reincarnated lama, continues to sneak viewings of the series. With the film, Pema Tseden tries to address the loss of cultural values and religious practices.

Despite the strong reception by critics, Holy Stones did poorly on the mainland. Zhang recognises the challenge his team faces in attracting Han viewers, but insists that with a good scripts and high production values, the films can find a wide domestic audience.

Jiang Zhaoyong, a Beijing-based expert on ethnic issues, said a lack of economic opportunity and the government’s restrictions on religious expression stood behind growing estrangement among some minority groups in recent years.

“But, there are few TV dramas or movies reflecting such realities, which would help the inland Han better understand the bitter pain of the ethnic minority people.”