Beijing attempts to soothe small businesses’ social tax fears as trade war dims growth outlook

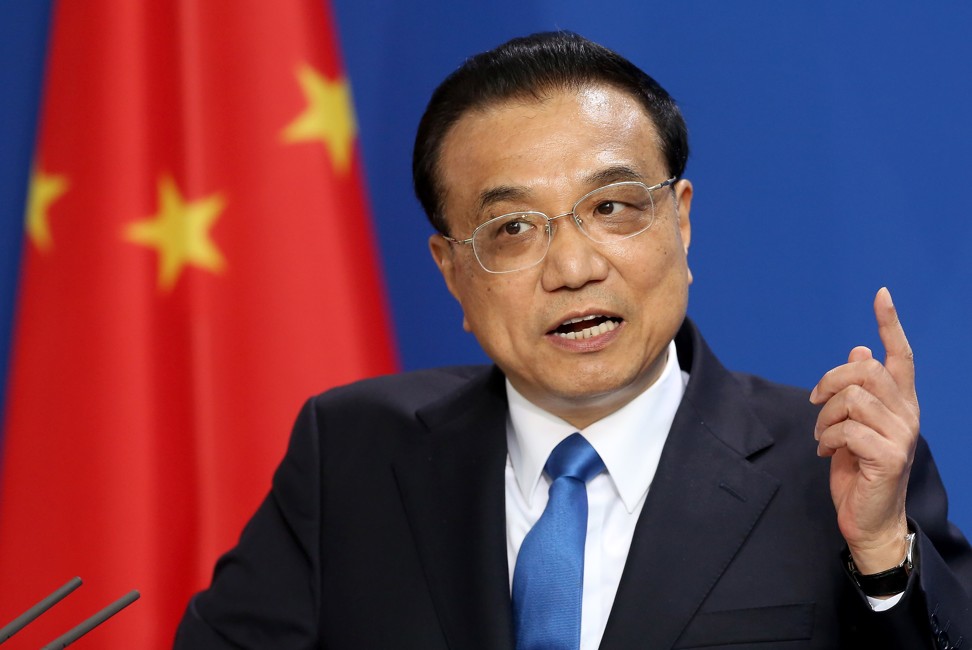

Premier Li Keqiang promises to maintain status quo amid fears small firms could be driven out of business

Beijing has taken the unusual step of assuring China’s small businesses that the government will not abruptly raise their social tax burdens after a planned regulatory change to tighten fee collection stirred fury and fear among small manufacturers.

At a regular State Council meeting on Thursday, Premier Li Keqiang promised the government would maintain for now the status quo on the collection of corporate contributions to social funds and would study lowering social welfare contribution rates to ensure “there is no increase in the corporate burden”.

The move is a clear attempt to assuage the concerns of many small, private factory owners who fear they will be driven out of business if they are forced to pay their social welfare fees in full.

Chinese employers are obliged to pay several social taxes every month based on their workers’ wages. These comprise contributions to the national social security fund (equivalent to 19 per cent of the total payroll), health care insurance fund (10 per cent), and unemployment, work injury and childbirth insurance (about 2 per cent).

Implementation of social payment rules, however, is often lax, especially among small, private sector manufacturers, and the authorities in charge of collection often tolerate underpayment. But from January the duty of collecting the fees will shift to local taxation bureaus, which will have the incentives and means to ensure businesses pay their dues in full.

This tightening of the collection process could deal another blow to China’s economy even as it struggles with slowing domestic demand and an escalating trade war with the United States. At the very least, the change could wipe out profits at many of China’s private businesses.

A report by brokerage Guotai Junan Securities estimated that the rule change would cost Chinese employers an extra 2 trillion yuan (US$292.16 billion) next year, or about the same as the combined profits of all of China’s privately owned businesses in 2017.

Jason Zhang, who runs a factory in the southern city of Shenzhen making cables for smartphones and computers, said it would cost him about 1 million yuan a month if he was forced to pay social welfare fees strictly in line with state regulations.

Zhang said he currently pays social welfare fees for about half of his 800 workers and that his profit would be wiped out if he paid the full amount. Even without the higher costs, Zhang said his factory’s 10 million yuan profit in 2017 would drop by 30 per cent due to falling demand if the US imposed tariffs on Chinese electronic components, as it had threatened to do.

The new social welfare collection rule could be the straw that broke the camel’s back for his business and many similar factories, he said.

“A lot of entrepreneurs like me cannot afford such a drastic change,” Zhang said.

Concern about social welfare fees is part of a bigger debate on whether the government is taxing Chinese businesses and individuals too heavily, especially after the US and other countries cut their tax rates. Appeals for Beijing to cut business taxes to improve competitiveness have increased since US President Donald Trump signed into law in December a reduction in the corporate income tax rate from 35 per cent to about 21 per cent.

The Chinese government has already promised to reduce the burden of tax and fees on businesses. In its annual work report in March, Li said he would cut the corporate tax burden by 800 billion yuan and administrative fees by a further 300 billion yuan this year.

However, many small firms may not feel any easing of their burden as a result of stricter collection methods by tax authorities.

For example, some Chinese venture capital funds were abruptly told by the tax authorities last month that they should pay the full 35 per cent tax rate on their income instead of a preferential 20 per cent rate they had been allowed to pay for years.

The planned change prompted the China Merger and Acquisition Association, an industry group, to appeal to the government to avoid raising taxes on venture capital firms at a time when the country is trying to finance a series of new hi-tech initiatives.

Li touched the issue on Thursday, ordering tax authorities not to increase the “overall tax burden” on venture capitalists.

Wu Qi, a senior fellow at the Beijing-based Pangoal Institute, said China needed to enact meaningful tax cuts for small, private sector businesses amid the nation’s broad economic slowdown and the external headwinds caused by the trade war.

Such cuts would “be the most effective tool” to help stabilise growth, as the government had vowed to do and had the capacity to do, Wu said.

China’s tax revenue in the first seven months of the year rose 14 per cent from the same period of 2017 to 10.8 trillion yuan. The rate was more than twice the 6.8 per cent by which the nation’s gross domestic product rose in the first half of the year.

Tang Dajie, secretary general of the China Enterprise Institute, said a rapid rise in the cost of raw materials, rents, taxes and social security payments this year had created a major threat to the viability of private firms.

Despite Beijing’s promise to cut social security contribution rates, Tang said only a few rich provinces would be able to do so given the government’s initiative to rein in local government debt. When the social contribution rate was reduced several years ago, only a few provinces cut it by 1 percentage point to 19 per cent.

Tang said China should also slash its value-added tax rates as they were are among the highest in the world. In May, Beijing trimmed the highest VAT band by 1 percentage point to 16 per cent.