Opinion: why Afghanistan’s stability is so important to China

China has become increasingly more proactive and committed to its neighbour Afghanistan’s stability since 2014. That year, Beijing sent no fewer than three high level officials, including Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, to Afghanistan.

It also hosted the fourth foreign ministers’ meeting of the annual Heart of Asia process - an effort by the international community launched in late 2011 to engage Afghanistan’s extended neighbours and relevant organisations in the country’s reconstruction. China’s hosting of this event gave the process a big boost.

Following this, China coordinated various meetings on Afghanistan with regional stakeholders, including Iran, Pakistan and Russia.

China has even conversed with representatives of the Taliban, Afghanistan’s primary insurgency group, and is one of the four members of the now dormant and so far ineffective, Quadrilateral Coordination Group. This group, comprised of Afghanistan, China, Pakistan and the US, intends to coordinate Afghan political reconciliation through talks with the Taliban.

In addition, Beijing has committed more aid to Afghanistan, post-2014, than in the entire period from 2001 to 2013.

Since international forces substantially scaled down in Afghanistan in 2014, the insurgency has made notable advances. Government forces and the insurgency now find themselves in a military deadlock.

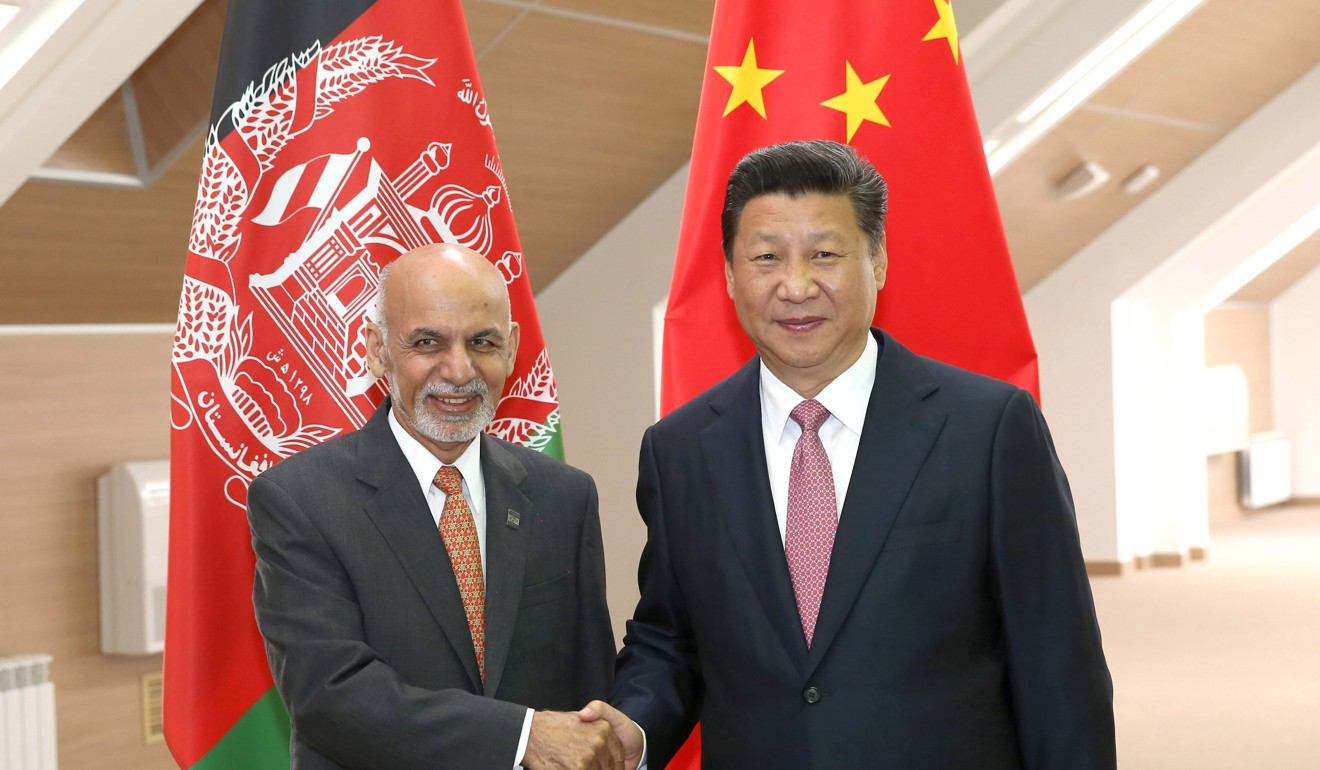

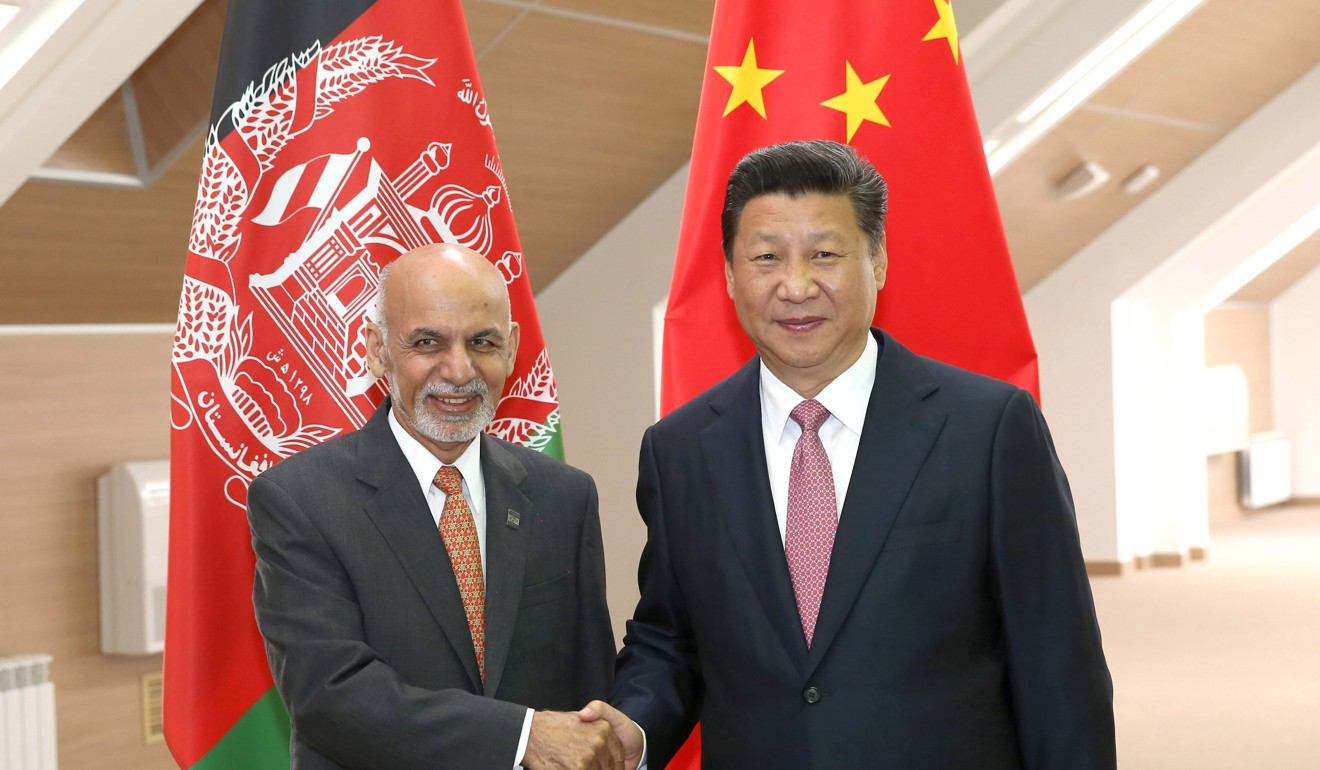

This is against the backdrop of mutually reinforcing political, socioeconomic and security crises out of which the national unity government headed by President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah does not seem able to break. The government has welcomed closer Chinese support.

Afghanistan’s instability affects China’s own stability, particularly that of its terrorism-prone Xinjiang region. Members of the Turkistan Islamic Party, a Xinjiang-focused Islamic separatist group, have been apprehended in Afghanistan. China fears that an unstable Afghanistan will permit greater use of Afghan territory by the militants to plot attacks on Chinese territory and sustain the country’s thriving drug industry. This can threaten social stability in China and the perceived ability of the Chinese government to protect the populace from harm.

In addition, the Islamic State Khorasan branch threat in South Asia is growing. In Afghanistan, it is based in its eastern Nangarhar province, close to the border with Pakistan. IS-K has regional aspirations that include Central Asia and nearly stretch into China’s western borders.

China also realises that as long as Afghanistan is unstable, US and Nato forces will have a reason to sustain a military presence there - only kilometres from China’s border. Under the current security circumstances in Afghanistan, China welcomes this, but does not wish to see this prolonged more than necessary.

This ties into China’s aspiration to create a buffer of stable, functional and prosperous neighbouring states - no fewer than 14 in China’s case - that will amply rely on the Chinese economy and pose a limited threat to Chinese stability, either directly or indirectly. This notion has compelled China to step up as a regional security actor, as it is doing in Afghanistan.

In China’s view, there is limited security without economic development, which itself cannot take off without basic infrastructure.

This in turn relates to the Belt and Road initiative. China is pouring tremendous human and financial resources into this endeavour. As a long-term vision for economic integration of the Eurasian continent, and even beyond, mitigating threats to both its implementation and the security of current and future transit of goods, energy and people is absolutely vital.

To make things worse, Afghan instability actually threatens the initiative’s corridors that run through the southern stretches of Central Asia, and its flagship project, the China-Pakistan economic corridor. It runs quite close to the border with Afghanistan, and Pakistan itself is prone to frequent terrorist attacks. Some of these, Pakistan claims, are plotted in Afghanistan.

Foreign policy is always an extension of domestic interests and thus China has, for all these reasons, decided to step up in regard to Afghanistan’s stability. Undoubtedly, there is also an altruistic interest to see Afghanistan stabilise and the Afghan people to flourish.

In time to come, China will have its hands full with not only trying to better understand the complex dynamics of peace and conflict in Afghanistan and the region, but also making sure that its increased commitment bears fruit.

Richard Ghiasy is researcher at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s China and Global Security Programme