How Nepal’s cancelled dam scheme highlights country’s big debate: ally with India or China?

Decision to cancel infrastructure project throws focus onto internal divisions between pro-Beijing and pro-Delhi factions

The question of whether Nepal should go ahead with plans to build a dam with a Chinese firm has become entwined in the wider debate about whether the country should align itself with India or China.

The Nepalese government indicated last week it would abandon the US$2.5 billion deal with Chinese state company China Gezhouba Group.

The deal was signed in June during the administration of Pushpa Kamal Dahal, chairman of the Maoist Centre party, but his government has since been replaced by an interim administration ahead of elections later this month.

Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli – the chairman of the electoral bloc formed by Maoist Centre and the other main Communist group, the Unified Marxist-Leninists – warned against revoking the plan.

“The issue here is about foreign investment and such decisions cannot be taken on a whim,” he said, as the polls for the November 26 provincial and federal elections showed his bloc to be taking the lead.

The decision to scrap the project highlights Nepal’s divisions over how close the country should be to China, which has emerged as an alternative to its traditional ally India.

Yet the country’s political instability, which has already seen four prime ministers come and go since it adopted a new constitution in September 2015, makes it even more difficult to strike the correct balance between the neighbouring Asian giants.

Nepal’s political institutions emerged as part of the peace process to bring Maoist insurgents into the political mainstream following a long-running insurgency.

The dam agreement, signed a few weeks after Nepal joined China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”, was described by Deputy Prime Minister Kamal Thapa as being made “in an irregular and thoughtless manner” when he first revealed the cabinet decision via Twitter on Monday.

The formal decision to scrap the plan was announced by the Ministry of Energy on Friday.

The plan has been criticised because a memorandum of understanding with the Chinese company was signed without an open bidding process as required by law.

Rupak Sapkota, a researcher at Nepal Institute for Strategic Analyses, said the scrapping of the plan was the result of conflict between Nepalese political factions over their respective alignment with India and China.

“Nepal is still trying to figure out a balanced position between India and China,” he said.

He said the present Congress Party-led government – a transitional one formed ahead of the election – was known to be more pro-India and was trying to show loyalty to Delhi before, assuming the polls were correct, it was replaced by the more pro-China Maoist bloc.

Yet, Madhav Das Nalapat, a geopolitics expert from India’s Manipal University, said the cancelling of the plan “is not reflective of domestic politics but of domestic economic imperatives”.

He said China’s negotiation tactics when dealing with countries such as Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Nepal and Pakistan mirrored the hard-headed approach of US or European Union companies rather than offering “friendly” terms and conditions.

Water-rich Nepal has traditionally relied on India for technology and funding to meet its annual requirements of 1,400 megawatts.

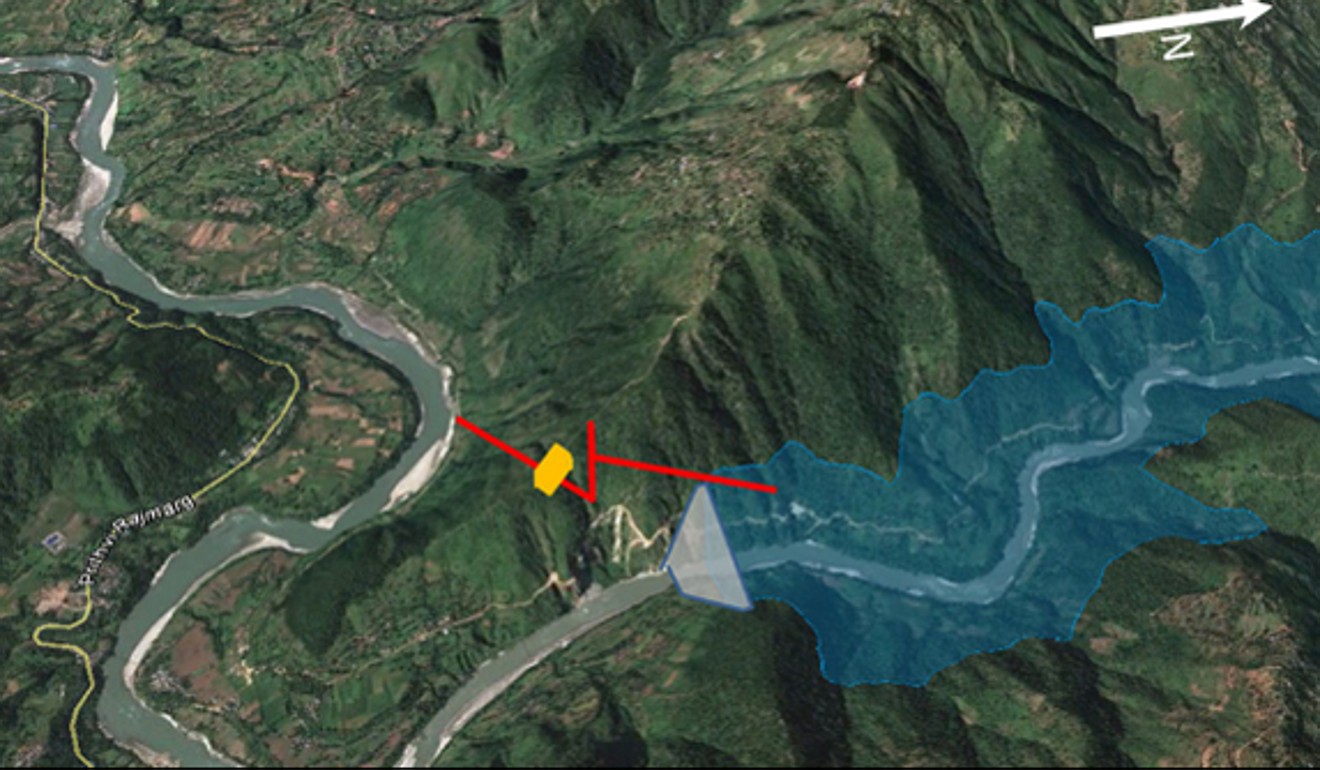

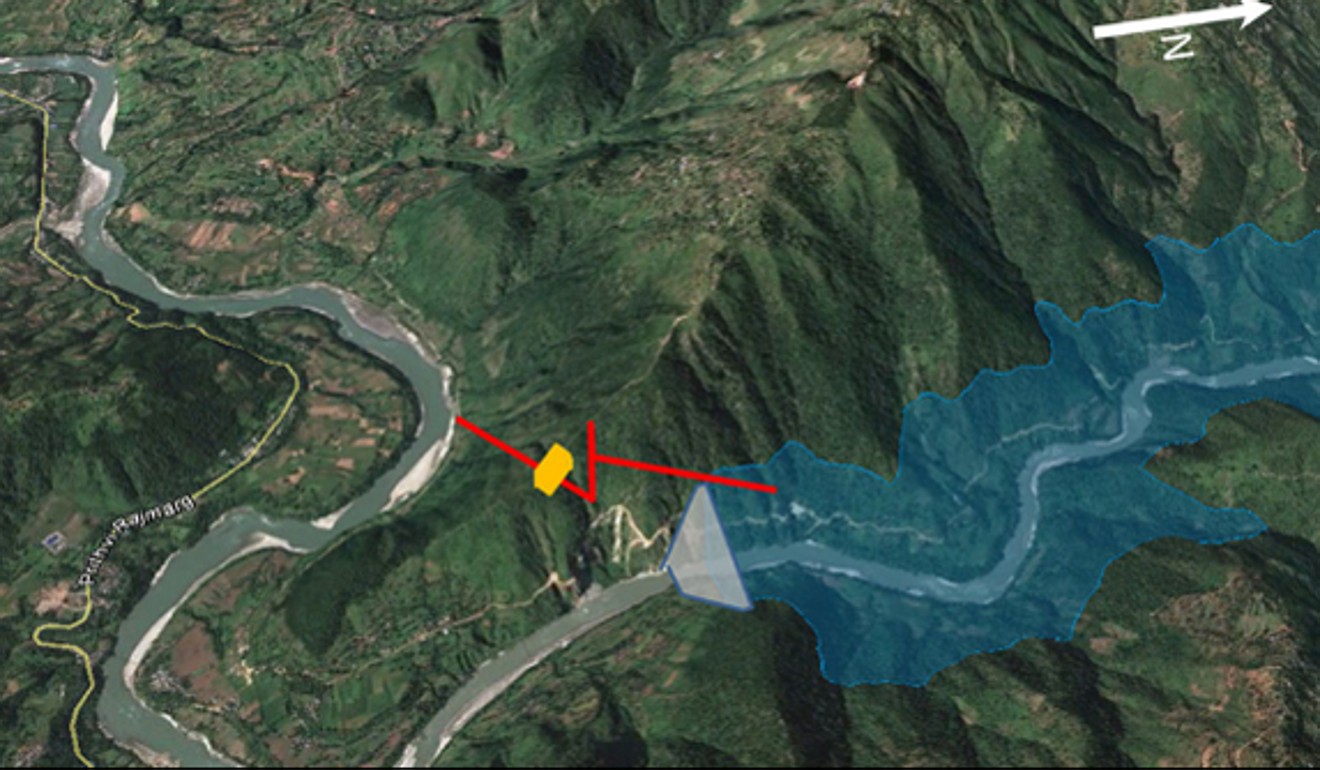

Should the project go ahead, the Budhi Gandaki dam – to be built about 50km west of Kathmandu – could generate 1,200MW.

Sapkota said Nepal needed more hydroelectric power to help improve the lives of people as well as boost the economy. “We have been waiting for a long time,” he said.

Domestic political divides over whether to engage with China’s belt and road plans to build an infrastructure network across Eurasia and into Africa are hardly exclusive to Nepal.

This week Pakistan also decided to cancel the US$14 billion Diamer-Bhasha dam with China because it could not accept the strict conditions.

In 2015 the Sri Lankan government suspended work on a US$1.4 billion Colombo port deal made by a previous administration, as it faced criticism domestically for being too reliant on Chinese investment.

However last year it decided to resume the project due to its falling foreign reserves.

“Whenever India indicates discreetly that a ‘red line’ has been crossed in a South Asian country’s wooing of China, that country usually draws back rather than trigger a negative reaction from the largest South Asian power. The present government in Kathmandu is following such a line,” Nalapat said.

Zhao Gancheng, head of South Asian studies at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies, said this had always been a challenge for China as it continued to increase its investments in developing countries.

“China needs to protect itself more to guarantee that it is signing the deal with the whole country, not the person governing it at that moment,” Zhao said.

“If Nepal shows that its priority is to cater to India whenever pressure is applied, China should be more aware of its own interests and take careful consideration before funding projects in the country in the future.”