Is tide turning for US-China ties under Trump?

US president the first to use national security strategy to label China a strategic competitor

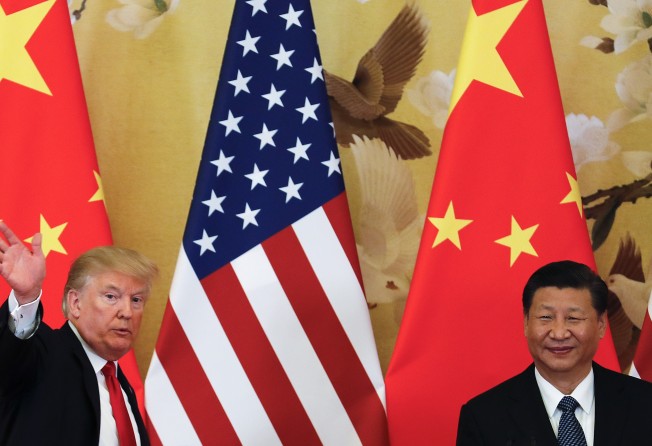

When US President Donald Trump branded China a revisionist, rival power this month he breathed new life into a decades-old policy debate in Washington: how to define US-China relations.

It is a conundrum that has confronted every American president since Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China, which marked the beginning of the rapprochement between the two cold war foes.

Policymakers, politicians and think tanks in both countries revisit the question every few years, trying to redefine the complex bilateral relationship.

It is not the first time China has been labelled a strategic competitor to the United States, with Washington’s China policy having swung between containment and engagement in the back and forth policy debate since the normalisation of diplomatic relations in 1979.

But Trump became the first US president to spell it out officially in America’s national security strategy, a policy paper required by the US Congress since the mid-1980s.

In his most comprehensive foreign policy statement, delivered nearly a year after he took office, Trump catalogued mounting security and economic threats posed by China and accused Beijing of using its repressive vision of a new world order and economic aggression to undermine American security and “displace the US in the Indo-Pacific region”.

While critics say Trump’s broadside just stated the obvious, without prescribing solutions, others argue Trump’s move to list Beijing as a global threat should be taken seriously despite his unpredictability and incoherence when it comes to foreign policy issues.

They say it reflects a growing consensus within the US foreign policy establishment towards Beijing’s muscle-flexing in Asia under President Xi Jinping and a sea change in Americans’ perception of China in the past decade, especially after China surpassed Japan as the world’s second largest economy in 2010.

Surveys by the Washington-based Pew Research Centre have found Americans’ overall impressions of China have steadily deteriorated due to tensions over the South China Sea and constant frictions on trade, security and human rights issues. Nearly half the American public now see China’s emergence as a world power as a major threat to the US, up from less than 40 per cent 10 years ago.

Two years ago, Jeffrey Bader, an Asia adviser to US presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, observed that the changing balance of power between the two countries was nearing a tipping point, with the bilateral relationship shifting from one that was predominantly cooperative to one based primarily on overt rivalry.

Pundits said Xi’s global ambition, which he spelt out at the Communist Party’s national congress in October, would alarm the Trump White House, feed into the anti-China narrative in Western countries and exacerbate the potential for rivalry between a rising China and the US, the only global superpower.

Xi, who has just been confirmed as China’s most powerful leader in decades, declared at the party congress that China had entered a new era and was ready to take the centre of the international stage and promote the China model as an alternative development option for other nations.

“It’s probably a time of confrontation,” said Ma Zhengang, a former Chinese ambassador to Britain and a former president of the China Institute of International Studies. “China’s rise will face more arduous tasks and challenges as the dominant powers will seek to maintain their control of the international order and crank up the heat and rhetoric on China threats.”

Observers said that despite the personal rapport the US president had developed with Xi since their first summit in Florida in April, Trump appeared to have returned to his hardline campaign stance on China, spurred on by the more hawkish, China-bashing voices in his administration.

“For decades, US policy was rooted in the belief that support for China’s rise and for its integration into the post-war international order would liberalise China. Contrary to our hopes, China expanded its power at the expense of the sovereignty of others,” Trump said when releasing his national security strategy on December 18.

He declared that great power rivalry, previously dismissed as the preoccupation of a bygone era, had returned.

Taken aback by Trump’s about-face, just a month after he was feted with elaborate pageantry in the Chinese capital during his “state visit plus”, Beijing denounced his remarks as another US attempt, driven by “cold war mentality”, to prevent China from becoming an equal power.

Trump’s statement could usher in a new chapter for bilateral ties, observers said, following the normalisation period under US presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, the brief disruption after the bloody 1989 Tiananmen crackdown and the fervent policy of economic engagement embraced by administrations from George H.W. Bush to Barack Obama.

Ties were “entering the third phase, where we’re once again defining China principally as a strategic competitor both in economics and security”, said David Lampton, director of China studies at Johns Hopkins University’s school of advanced international studies and a former president of the National Committee on US-China Relations.

Lampton said the Republican Party’s effort to identify China as a strategic competitor had been delayed for more than 16 years.

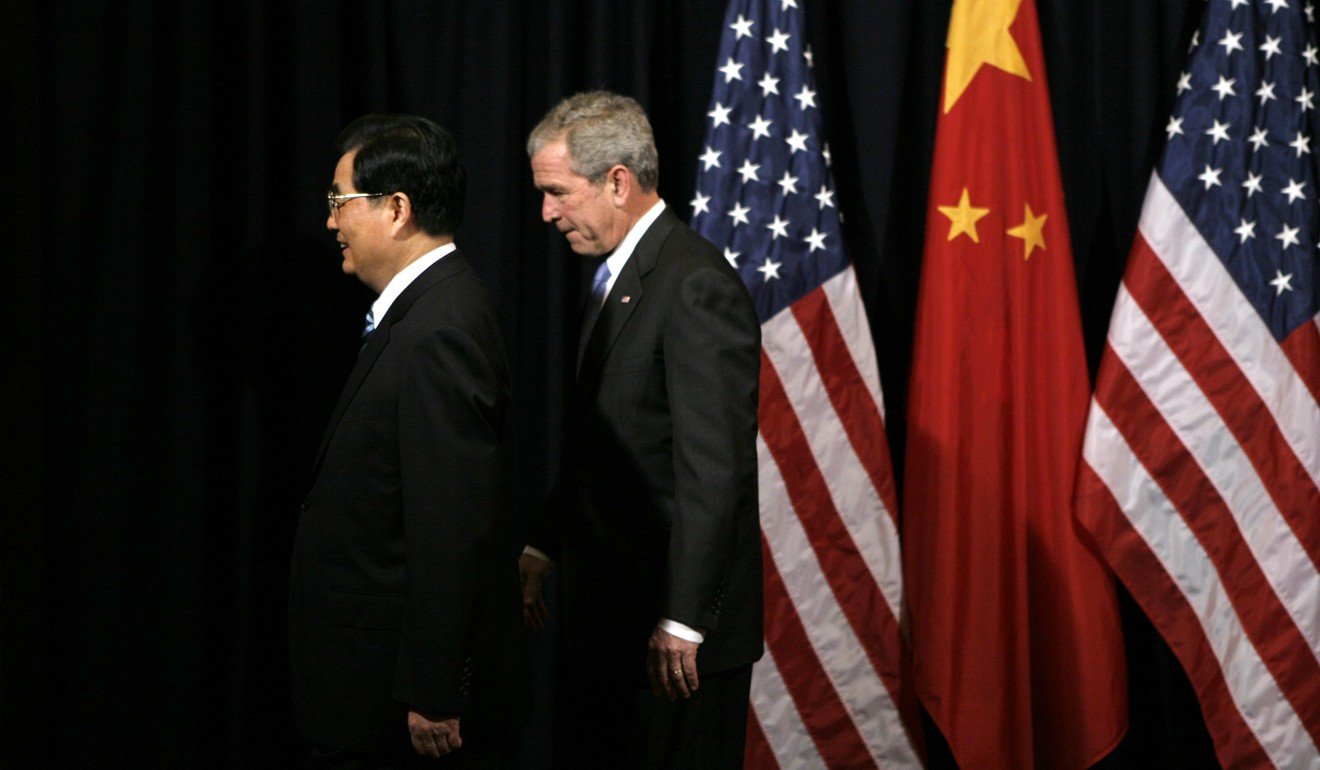

George W. Bush famously declared during the 2000 election campaign that China was a “strategic competitor”, a concept developed by his chief diplomatic adviser Condoleezza Rice, who later served as his national security adviser and then secretary of state.

As a candidate, the younger Bush strongly criticised Clinton’s “constructive strategic partnership” and “blind engagement” with China, which paved the way for Beijing’s accession to the World Trade Organisation in December 2001, at the end of Bush’s first year in office.

While he looked set to carry out his hardline anti-China agenda after a fatal collision between a Chinese military interceptor and a US Navy spy plane near Hainan in April 2001, the terror attacks on the US on September 11 that year changed the course of history, with Washington moving closer to Beijing, which offered support for Bush’s global war on terror due to its own concerns about Islamic extremism and Uygur separatism in Xinjiang.

Dating back to the Reagan era, US presidents have followed a pattern of appearing to be tough on China during election campaigns, and even in their first few months in office, before backtracking on such aggressive rhetoric.

With China going through tremendous changes at a time of declining US leadership in a fast-changing geopolitical landscape, American politicians have, over the years, variously billed the country as a trade and strategic partner, a responsible stakeholder, a competitor or even a robust rival.

Reagan, whose foreign policy mantra of “peace through strength” has effectively been revived under Trump, was the first US leader to see China as a strategic partner.

His relations with Beijing got off to a rocky start over America’s continued arms sales to Taiwan despite his administration’s pledge to gradually limit such deliveries in a vaguely worded communiqué with Beijing in August 1982.

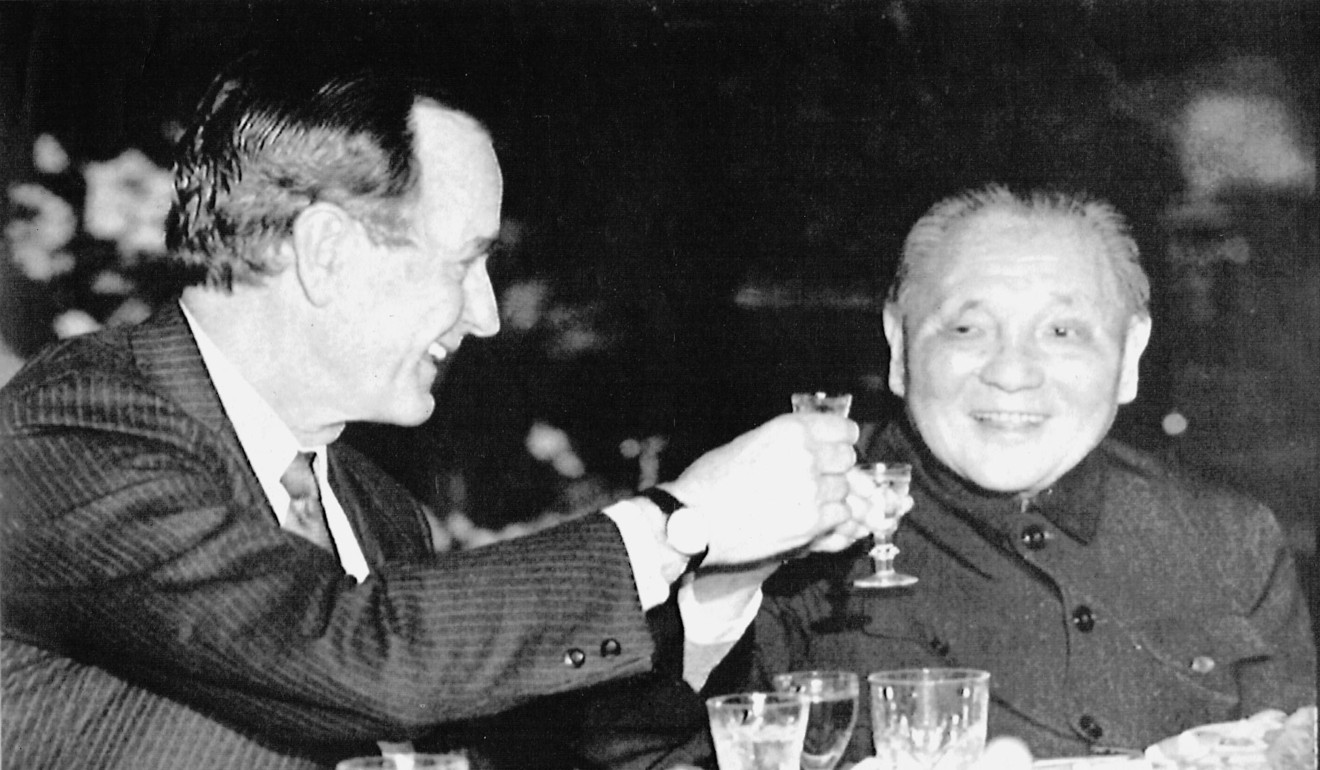

But like Nixon and Carter, Reagan, a fervent anti-communist, soon realised he had to come to terms with China’s paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping, to “write the final pages of the history of the Soviet Union”, which he described as an expansionist “evil empire”.

To win Beijing’s support for his battle to thwart Soviet hegemony, he decided to reset bilateral ties and forge a “global, strategic” partnership with China, including the launch of groundbreaking military and intelligence cooperation.

More importantly for Beijing, Reagan also quietly dropped his campaign pledge to restore official relations with Taipei, which has been the most delicate issue in Beijing’s love-hate relationship with Washington.

On a high-profile visit to Beijing in 1984, Reagan tactfully set aside differences with Beijing on Taiwan and ideology while using almost every public forum to denounce the Soviet Union. Beijing was uncomfortable with his blistering attack on a fellow communist regime and censored those remarks.

Like Reagan, Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama also bashed China on the campaign trail but changed the tune once inaugurated.

US-China relations were not pulled “out of the thin air” and it was no coincidence that eight presidents since Nixon had all chosen to avoid adopting a confrontational approach to China, said Stapleton Roy, who served as US ambassador in Beijing under George H.W. Bush and Clinton from 1991 to 1995 and is founding director emeritus of the Kissinger Institute on China and the US at the Woodrow Wilson International Centre in Washington.

“The two countries have found that even with the Soviet threat being removed, we still find it better to cooperate with each other than to get into confrontation with each other,” he said. “That’s not going to change whoever becomes [US] president.

“The pattern in US politics is that our new presidents would often get off on the wrong foot in dealing with China. President Clinton is an example. Then they have to come back to a recognition that US interests were not advanced by having confrontational relations with China.”

Clinton’s contentious decision to link China’s human rights situation to the granting of most-favoured-nation trade status saw his presidency marred by frequent spats with Beijing.

He reversed the policy a year after he took office and pledged to “take a new path” with China, banking on closer economic ties to increase US influence on Beijing.

Keenly aware of growing fears over China’s rapid economic growth and the “China threat theory”, Beijing rolled out a “peaceful development” policy in 2004, under Xi’s predecessor Hu Jintao, that is still is use today.

Originally known as “peaceful rise”, the concept was first coined by Zheng Bijian, a top government adviser and former vice-president of the Central Party School.

“In my judgment, Zheng correctly assessed the international environment and decided that China’s interests will be best served by peaceful rise because of the historical pattern when a rising country gets into military conflicts with the established countries around it,” Roy said.

But he said the way China had thrown its weight around had not matched those lofty pledges, and that had created frictions with its neighbours and pushed them closer to Washington.

In response to Beijing’s peaceful rise proposal, deputy secretary of state Robert Zoellick put forward the concept of the “responsible stakeholder” in September 2005. One of the most consequential efforts to redefine US-China relations, it appealed for China to properly use its growing international clout and shoulder greater responsibility in solving hotspots such as Iran, Sudan and North Korea.

“China has a responsibility to strengthen the international system that has enabled its success,” Zoellick said. “In doing so, China could achieve the objective identified by Mr Zheng: ‘to transcend the traditional ways for great powers to emerge’.”

Following the Obama administration’s “pivot to Asia” policy in 2011, widely seen as a renewed containment policy targeting China, Xi pushed for a “new type of great power relations” during his 2013 summit with Obama in California.

Xi’s formula for China-US relations, based on “non-conflict, non-confrontation, mutual respect and win-win cooperation”, was given the cold shoulder by the Obama White House amid concerns it would be tantamount to granting Beijing “equal power status”.

Trump’s Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, came under fire for echoing Xi’s formula during his first trip to Beijing in March, which was seen as kowtowing to Beijing and proof of the Trump administration’s incompetence.

Many experts agreed the 2008 global financial crisis was a watershed moment in the balance of power between the two countries.

“The global financial crisis lowered the prestige of the Western economies and enabled China to pass Japan as the world’s second largest economy and catch up closer to the US much faster than expected,” Roy said.

Yuan Peng, vice-president of the Chinese Institute of Contemporary International Relations, said last year that China had made the best of the strategic opportunity to narrow the gap in relative power between China and the US, and that the two countries might be entering an era of growing competition and even strategic rivalry.

“Economic and trade cooperation is serving as the ‘ballast’ of bilateral ties at the moment, but over time, the ballast may morph into a point of friction when competition overrides complementarity,” he said.

Additional reporting by Robert Delaney