How India became China-led development bank’s main borrower

Almost 28 per cent of the money lent by AIIB in first two years of operation has gone to projects in India

Territorial disputes between China and India have not stopped India becoming the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank’s (AIIB) top borrower.

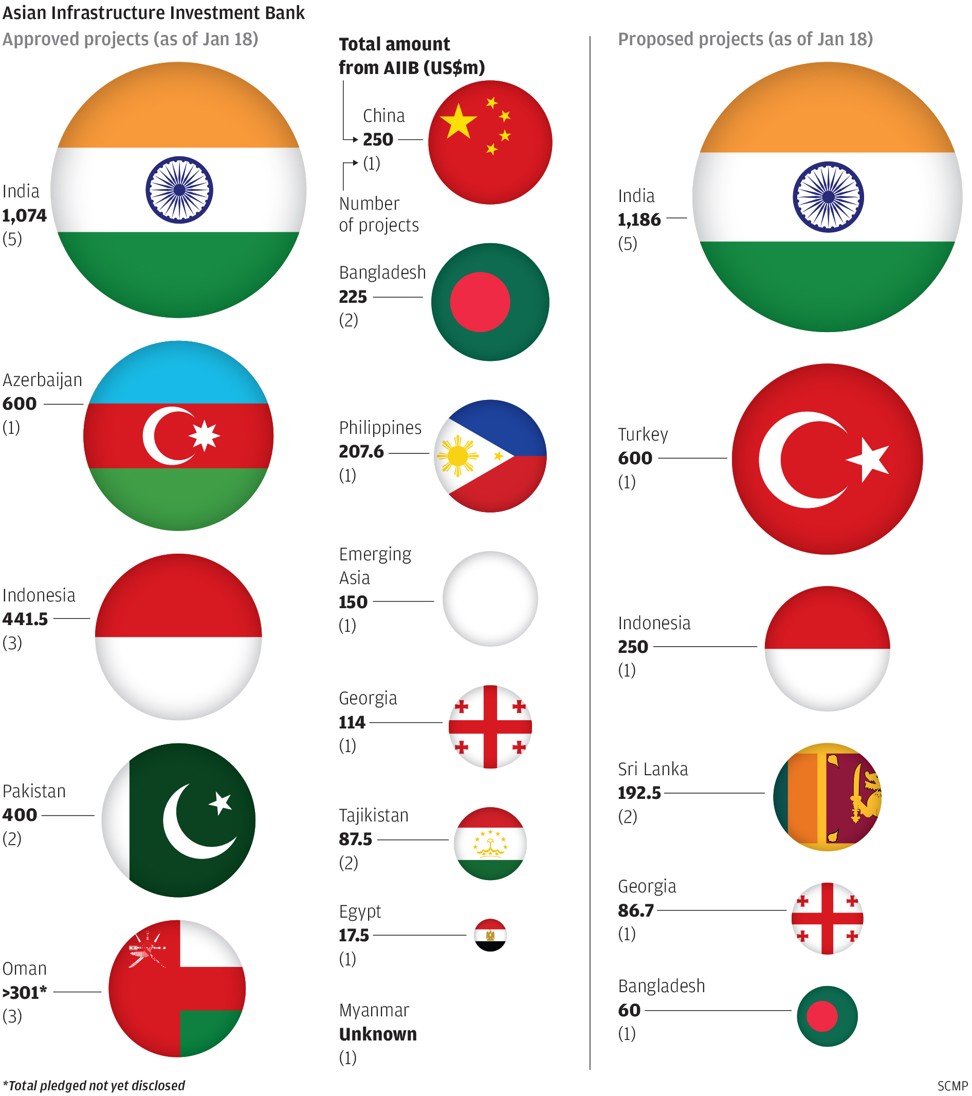

The AIIB, which celebrated it second anniversary this week, has approved funding for 24 infrastructure projects, five of them in India, bank data shows, with its loans to the Indian projects – totalling US$1.074 billion – accounting for almost 28 per cent of the money it has lent.

“India and China may have disputes – a common scenario for big neighbouring countries – but business is business,” said Zhao Gancheng, director of South Asia studies at the Shanghai Institute for International Studies.

Indian and Chinese troops were engaged in a tense border stand-off on the Doklam plateau, in the Himalayas near Bhutan, for months last year, while New Delhi also boycotted Beijing’s “Belt and Road Initiative” forum last May and warned countries involved in the trade-development scheme they risked being saddled with “unsustainable debt burdens”.

Indian scholars have also portrayed China’s port-building activities in Pakistan, Sri Lanka and elsewhere in India’s backyard as “a string of pearls” designed to contain their country, while Chinese investment in and loans to Nepal and Sri Lanka have also sparked unease.

New Delhi is also trying to rein in a bilateral trade deficit that amounted to US$51 billion last financial year – on two-way trade totalling US$71.5 billion.

The AIIB, a multilateral development bank first proposed by President Xi Jinping in 2013, opened for business on January 16, 2016.

It focuses on funding the construction of roads, railway lines, ports and energy and rural infrastructure, mainly in Asia, and currently has 84 member countries, with China holding just under 27 per cent of its voting shares. That gives Beijing effective veto power, as major bank decisions require at least 75 per cent support.

India is the second largest shareholder, with 7.7 per cent of the votes, followed by Russia with 6.1 per cent and Germany with 4.27 per cent.

Xi also proposed the belt and road plan in 2013, with the aim of building infrastructure to better connect China, Europe and countries in between.

AIIB head Jin Liqun has dismissed allegations that one of the bank’s roles is to support the growth of China’s soft power, saying it had its own operating standards.

Even though India had been reluctant to join the belt and road plan, Amitendu Palit, a senior research fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore, said it had always been an enthusiastic supporter of the AIIB, which had adopted a multi-country, rules-based style of governance.

“The AIIB has acquired the status of a plurilateral lending initiative, so there is no problem for either India, or China, in overlooking bilateral differences and working together at the AIIB,” he said, adding that India wanted to open up investment opportunities in the region.

“Unlike the AIIB, which is being guided by transparent procedures and clear rules of law, [belt and road] projects and funding patterns are ambiguous. It is, until now, more an initiative where countries are bilaterally negotiating with China to obtain funding for projects.”

Palit said India’s main concern about the belt and road scheme, apart from the lack of transparency in decision making, centred on the development of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which passed through territory claimed by both India and Pakistan.

Zhao said China’s support of lending to India through the AIIB was a “completely business-based decision, like any other banks”.

“Investing in India is beneficial for China because the country is one of the most economically and politically stable countries in the region,” he said.

The biggest AIIB loan to an Indian project approved so far has been US$335 million for a metro rail project in the southern Indian city of Bangalore that includes 13.6 miles (22km) of railway line and 18 stations.

The European Investment Bank lent €500 million (US$609.5 million) to the project two months before the AIIB.

India also has the most applications for AIIB funding awaiting approval, involving five projects seeking to borrow a total of US$1.19 billion. One of them, a metro line in the west coast city of Mumbai, is asking for US$500 million, which would be the AIIB’s biggest loan if approved.

Madhav Das Nalapat, director of the department of geopolitics and international relations at Manipal University, said he expected other Chinese banks would become big lenders to Indian companies, given the country’s vast funding needs and its “impeccable record” when it came to repaying loans.

“Once trade between India and China crosses US$300 billion annually, which it will in about five years, the two countries will be close friends,” Nalapat said.

But Palit said the likelihood of further Sino-Indian collaboration on matters of common interest did not mean bilateral differences would subside.

“Those would remain and both countries would have to work on those separately,” he said.

Additional reporting by Wendy Wu