For Prime Minister Mohammad Mahathir, revisiting China’s Malaysian projects is part of resetting a relationship

Richard Heydarian writes that the Malaysian PM, traditionally friendly with Beijing, may end some infrastructure projects if terms are not revised

Under Prime Minister Mohammad Mahathir’s second stint in power, Malaysia has begun to radically reassess its traditionally warm relations with China.

As one senior official told me during a recent visit to Kuala Lumpur, Chinese infrastructure projects could be axed amid concerns over economic viability, suffocating debt (US$250 billion), transparency of the contracts and domestic political pressure.

As a result, Malaysia, a top trading and investment partner of China, has surprisingly emerged as a new vortex of scepticism and resistance against Beijing’s growing influence in Southeast Asia.

Initially, many thought that Mahathir’s tough statements on Chinese investments were either election sloganeering to besmirch his China-friendly predecessor or part of a deliberate strategy to renegotiate large-scale infrastructure projects with Beijing for more favourable terms.

After all, the Malaysian prime minister has sung different tunes during his recent interviews, sometimes sounding more sceptical of China, at other times extending an olive branch.

What’s becoming increasingly clear, however, is that Malaysia’s new government is revisiting the whole development blueprint of its predecessor and is intent on reconfiguring overall relations with China.

Historically, Malaysia served as China’s most important economic partner in the region. During his earlier years in power, Mahathir, and later his successors, consciously cultivated stronger relations with Beijing as part of a broader strategy of economic development as well as non-alignment with the West.

As Mahathir told the South China Morning Post earlier this year, “I have always regarded China as a good neighbour, and also as a very big market for whatever it is that we produce.” He acknowledged the centrality of China to Malaysia as a “trading nation” and how economic interdependence means that “we can’t quarrel with such a big market”.

Yet China’s rapid rise in the past two decades has forced the Malaysian leader to revisit his earlier assumptions about relations with the Asian powerhouse.

His more strident stance was fully on display during Mahathir’s recent visit to Beijing, where he warned against “a new version of colonialism”. Developing countries like Malaysia, he said, “are unable to compete with rich countries in terms of just open, free trade” and he called for “fair trade”.

While falling short of directly naming China, the Malaysian leader reflected lingering frustration among smaller regional states over their increasingly asymmetrical trade and investments relations vis-à-vis Beijing.

Just two decades ago, many Southeast Asian countries held healthy trade balance with Beijing, with some, especially Singapore, emerging as major investors in China.

Nowadays, the terms of trade have radically transformed, with China a major source of capital, technology and manufacturing products in exchange for largely raw materials and low-value-added products from less developed Southeast Asian states.

The upshot is widening trade deficits with China, with some countries, particularly Laos, piling up unsustainable levels of debt.

Yet fears of a “debt trap” – with smaller countries like Sri Lanka forced to settle for debt-for-equity arrangements with Beijing – have forced even medium-sized, relatively developed states such as Malaysia to reassess their receptiveness to Chinese capital in recent years.

As Malaysia’s new finance minister, Lim Guan Eng, told The New York Times, “We don’t want a situation like Sri Lanka where they couldn’t pay and the Chinese ended up taking over the [funded] project.”

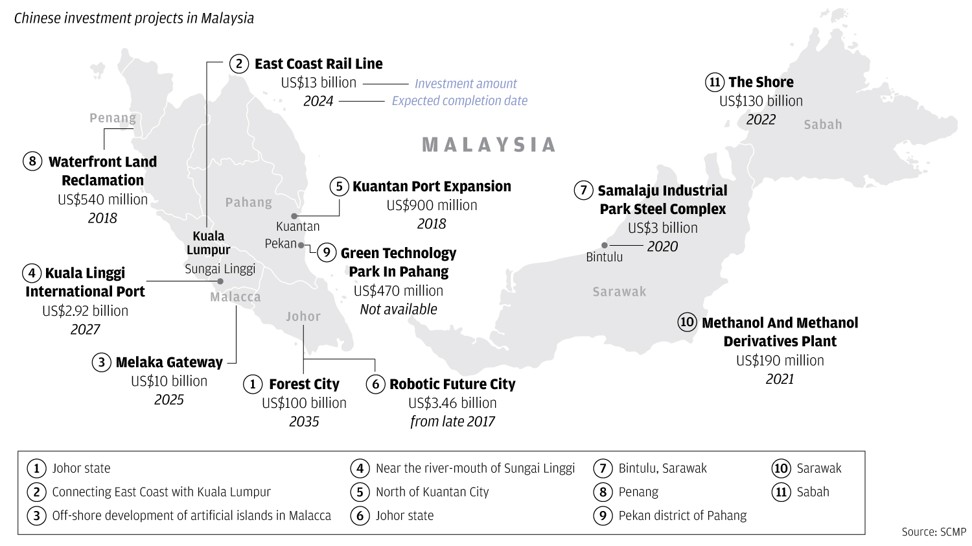

The Malaysian government is considering cancelling the East Coast Rail Link (estimated to cost close to US$20 billion when operations cost kick in), currently under construction by the state-owned China Communications Construction Company, as well as a pipeline construction agreement with a subsidiary of the China National Petroleum Corporation (worth US$2.5 billion).

It is also reconsidering the expansion of the Malaysia-China Kuantan Industrial Park as well as the Melaka Gateway mega-project, a US$10 billion development initiative based on a partnership between PowerChina International, two Chinese port developers and their Malaysian counterpart, KAJ Development.

The Mahathir government is seemingly willing to take the case to international arbitration if necessary, if Beijing were to challenge the cancellation of contracts.

Malaysia is also considering placing restrictions on purchases of residential units by Chinese and other foreigners at the US$100 billion Forest City project. The effect of such regulatory uncertainty and possible shifting on Chinese investment plans in Malaysia is likely to be significant.

That does not mean Malaysia isn’t open to Chinese investments. As Senator and Deputy Defence Minister Liew Chin Tong told me, the new government remains interested in “employment-generating” and “high-value-added” investments, especially in the realm of manufacturing, robotics and information technology.

What Malaysia wants, he said, is to be integrated into the broader China-driven regional production network as an equal partner on mutually beneficial terms. In short, Malaysia seeks an upgrade, rather than severance, of bilateral economic relations.