Why China’s eyeing of bankrupt Philippine shipyard sets off alarms in maritime Southeast Asia

- Richard Heydarian writes that China’s interest in giant Subic Bay shipyard, a former US naval base, triggers anxiety over Beijing’s growing influence

- At its peak, the world’s fifth largest shipyard had employed as many as 10,000 Filipinos

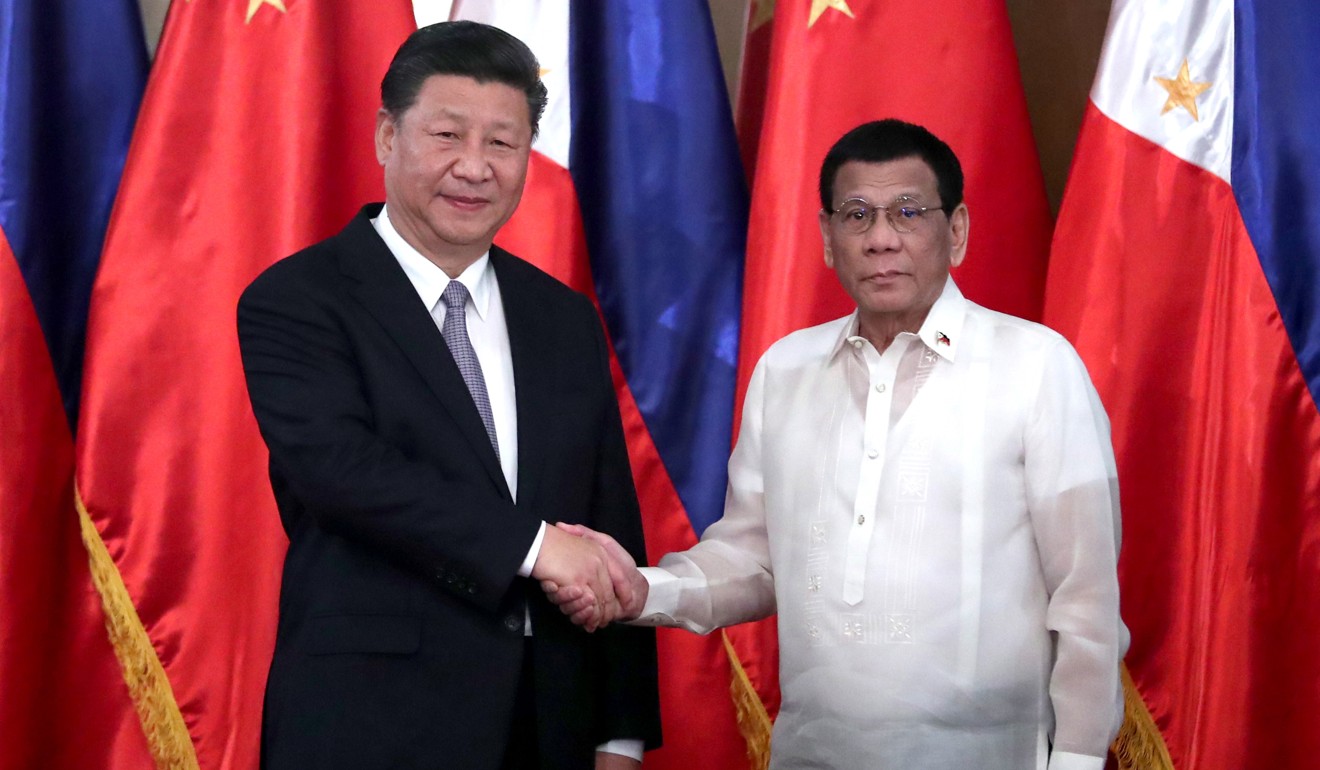

Since Rodrigo Duterte’s ascent to presidency, Philippine-China relations have undergone a strategic renaissance.

The Philippine president has assiduously downplayed South China Sea disputes in favour of warmer economic ties with China, an Asian juggernaut. Meanwhile, he has consciously downgraded the Philippines’ strategic ties with Western powers.

The prospective entry of state-affiliated Chinese companies into Philippine strategic sectors and locations, however, has sparked a backlash among the defence establishment, mainstream political elite and the broader public.

The most prominent manifestation of this trend is the nationwide uproar over China’s potential purchase of a large-scale shipyard in Subic Bay, the former site of the largest US overseas naval base.

Two Chinese companies have expressed interest in taking over the operation of the 300-hectare (741-acre) shipyard now run by the troubled Philippine subsidiary of South Korean shipbuilding giant Hanjin Heavy Industries and Construction.

Hanjin’s Philippine unit declared bankruptcy early this year after failing to service up to US$1.3 billion in accumulated debt. It sought the Philippine government’s help in finding new investors to protect the jobs of the 3,000 employees who still work at the site, on the island of Luzon in the Philippines, about 100km northwest of Manila Bay.

At one point, the Subic facility, the world’s fifth largest shipyard and a producer of some of the largest and most sophisticated vessels on the globe, had employed as many as 10,000 Filipinos.

More importantly, however, the shipyard is located near the industrial heartland of the Philippines and just over 100 nautical miles from the Scarborough Shoal.

The contested land mass was at the centre of an arbitral tribunal’s 2016 ruling that found no basis for Beijing’s claim over most of the South China Sea, home to some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

Under the Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement, a five-year-old US-Philippine pact designed to bolster the countries’ alliance, Manila and Washington initially had considered establishing semi-permanent American bases in Subic; the plan was shelved under Duterte’s presidency.

The US Navy, however, still enjoys regular access to Subic’s state-of-the-art deep water port facilities. Warships from other traditional Philippine allies, such as Japan and Australia, also regularly visit the area.

The greater Subic area also hosts annual Philippine-US Balikatan joint military exercises, which often showcase war games such as amphibious landing drills, with the South China Sea disputes in mind. (Balikatan is a Tagalog word meaning “shoulder to shoulder”.)

It’s precisely for these reasons that the Philippine defence establishment and prominent leaders have shown extreme sensitivity to China’s potential acquisition of the shipyard.

No less than Philippine Defence Secretary Delfin Lorenzana has openly opposed any Chinese takeover of the Hanjin facility.

He has instead advocated for the Philippine Navy to take over the facility for domestic warship production, especially as the Southeast Asian country embarks on a multibillion-dollar military modernisation programme increasingly focused on enhancing Philippine naval and air force capabilities.

“[W]e see the possibility of having our own shipbuilding capacity in the Philippines, especially large ships like what is being built by Hanjin shipyard in Subic,” the defence chief said in January.

Prominent political leaders such as Senator Grace Poe have also joined the chorus of opposition to any Chinese takeover in Subic. In a senate resolution, Poe described the facility as a “critical and strategic national asset” that should be kept out of the control of potentially hostile foreign entities.

The senator maintained that “security and control over Subic Bay are paramount to the security of the [South China Sea]” and to the Philippines’ “sovereign rights and jurisdiction” over contested area land features.

Citing the issue’s sensitivity, Philippine officials have refused to reveal the Chinese bidders’ identities, though they have disclosed that one is a state-affiliated company.

Chinese companies already operate a wide range of strategic port facilities, from Piraeus in Greece to Darwin in Australia. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ambitious infrastructure plan, the “Belt and Road Initiative”, Chinese companies have been involved in the construction and operation of 42 ports across more than 30 nations.

Chinese companies, such as China Merchants Group and China Ocean Shipping Company, have been at the centre of this “going global” strategy, which is transforming international maritime commerce.

Ahead of midterm elections, a referendum on Duterte’s controversial presidency, China’s growing investment footprint in the Philippines has come under closer scrutiny

Following Xi’s state visit to the Philippines in November, the two sides agreed to step up their cooperation under the belt and road umbrella. Thus, the Chinese takeover of a major shipyard in Subic should be seen as part of this bigger project.

Many Philippine officials, especially in Subic, hope that foreign investors will provide much-needed capital and logistical expertise to save the shipyard.

But fears persist, especially among China hawks in the Philippines, of a potential repeat of Sri Lanka’s experience, in which the state-affiliated China Harbour Engineering secured a 99-year lease over the Hambantota port as part of an equity-for-debt arrangement.

Others fear that Chinese operation of the shipyard will serve as a Trojan horse allowing Beijing to monitor the movement of US and other rival navies in the area.

Ahead of crucial midterm elections, which have quickly turned into a referendum on Duterte’s controversial presidency, China’s growing investment footprint in the Philippines has come under closer scrutiny.

The Philippine senate has conducted hearings on China Telecom’s entry into the Philippines’ telecommunication industry, citing potential threats to national security.

Last month, several senators, led by deputy Senate president Ralph Recto, blocked a US$400 million project between Philippine security agencies and China International Telecommunication Construction, a major surveillance technology company, by invoking national security considerations.

These actions have gone hand in hand with regular senate hearings and round-the-clock media coverage of the influx of Chinese illegal workers and Chinese gambling operations buying into the Philippine real estate market, squeezing out Filipino buyers and creating relatively few opportunities for local workers.

The ongoing Philippine-China rapprochement seems to have only exposed lingering anxieties over Beijing’s growing influence and investment reach.

Richard Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author