US-China trade war hits Africa’s cobalt and copper mines with 4,400 jobs expected to vanish

- Mining giant Glencore’s plan to shut a cobalt mine in Democratic Republic of Congo and two copper mining shafts in Zambia is due to weakening demand

- Tariff tit-for-tat between world’s two largest economies seen as one cause of weakening demand for African commodities used in a range of hi-tech products

The US-China trade war is partly to blame for Anglo-Swiss mining giant Glencore’s move to shut a cobalt mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo and copper mining shafts in Zambia, with the probable loss of about 4,400 jobs, analysts say.

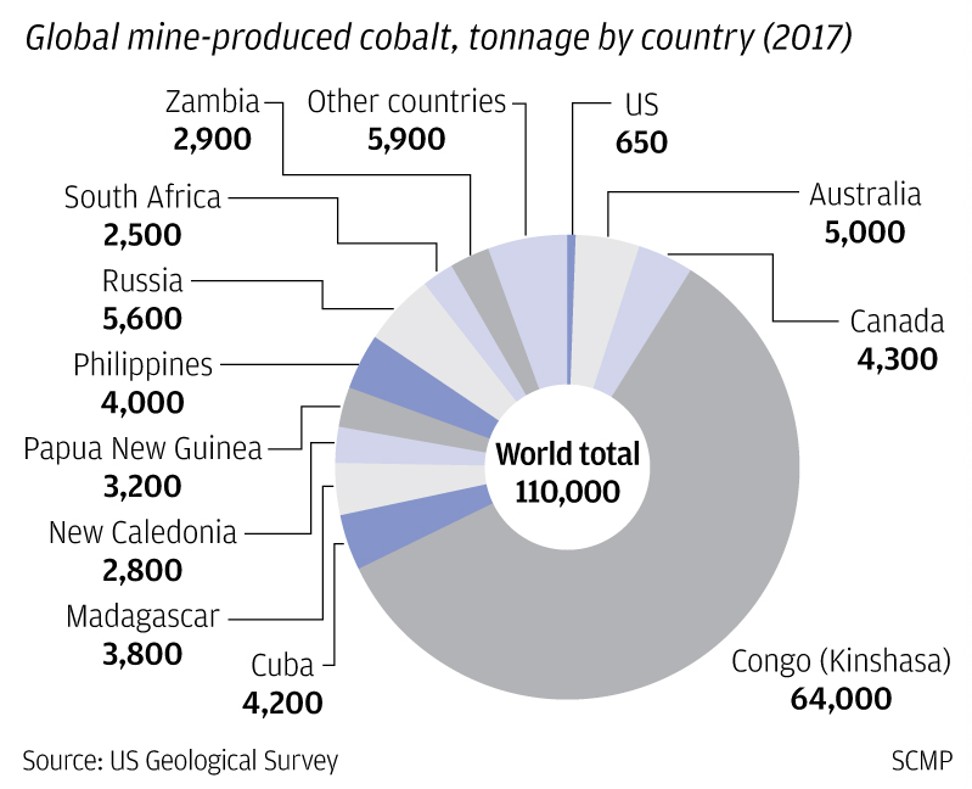

Glencore, which also is a commodity trading juggernaut, is placing its Mutanda mine in Congo – the world’s largest cobalt producer and one of the world’s poorest countries – on care and maintenance because of a slump in cobalt prices.

The mine, which produces about one-fifth of the metal used to make batteries for mobile phones and electric cars, provides about 3,000 jobs. It paid US$600 million in taxes last year, or one-tenth of the Congolese government’s budget.

Glencore’s Zambian unit, Mopani Copper Mines, is also shutting two copper mining shafts at its Nkana facility, probably putting 1,400 people out of work. Copper accounts for more than two-thirds of the country’s export revenue and a fifth of tax revenue.

The actions are a big blow for two countries whose economic and employment landscapes depend heavily on revenue from the copper and cobalt markets. Other African economies are also reeling from the slowdown in industries that consume the commodities they sell.

The 13-month trade war is partly responsible for weakening demand for the commodities the mines produce, according to analysts.

US President Donald Trump’s levying of 25 per cent tariffs on US$250 billion of Chinese products, and Beijing’s retaliatory taxes on US$110 billion of US goods are weighing on commodity prices and particularly on those for copper and cobalt.

The price of cobalt, an essential material in the rechargeable batteries that power smartphones and electric cars, has plunged from more than US$90,000 per tonne early last year to about US$28,000 per tonne, according to the London Metal Exchange.

John Ashbourne, a senior emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, a London-based economic research consultancy, said falling copper and cobalt prices were “adding yet another headwind to an economy that was already facing a drought and a worsening public debt crisis”.

“We’ve recently cut our growth forecast for Zambia to just 2 per cent, suggesting that income per capita will fall this year,” said Ashbourne, whose research focuses on Sub-Saharan Africa.

Lower-than-expected sales of electric cars in 2018 also have hurt demand for cobalt, resulting in electronics firms putting off purchases of the element.

Copper prices have also tumbled from a high of US$6,555 per tonne in February to about US$5,700.

But analysts say that while countries that export cobalt, copper and iron ore will be hardest hit as Beijing – the major buyer of Africa’s hard commodities – diversifies the sourcing of its imports during the trade war, opportunities are opening up for exporters of soft commodities, such as agricultural products.

The African Development Bank (AfDB) predicts that the trade war could lead to a 2.5 per cent drop in the gross domestic product of resource-rich African countries in three years.

Any commodity-exporting economy’s growth model has been underpinned by China’s demand in the last generation

The AfDB’s African Economic Outlook 2019 report noted that Africa’s chances of being hurt by the trade war were high, given that over 60 per cent of Africa’s exports go to the US, China and Europe, and more than 70 per cent of Africa’s imports originate from these countries.

“So, a decline in demand for Africa’s exports due to a slowdown in the global economy prompted by tariffs is an important channel that could affect Africa,” the AfDB wrote.

Analysts also blame the sluggish marketplace on new taxes that have raised the cost of doing business in those countries at a time of falling commodity prices.

A decelerating construction boom in China also has led to a decline in demand for copper while Beijing’s move to raise standards for electric vehicles qualifying for subsidies is depressing the market for cobalt.

An economic slowdown in some African countries is seen as tied to China’s economic slowdown, accelerated by the tariff battle.

The world’s second-largest economy grew at its slowest rate in 27 years in the second quarter, by 6.2 per cent, according to China’s Statistics office. The growth rate was 6.4 per cent in the first quarter.

Martyn Davies, managing director of emerging markets and Africa at Deloitte, said China’s demand for commodities has underpinned Africa’s growth for 20 years.

“Any commodity-exporting economy’s growth model has been underpinned by China’s demand for commodities in the last generation,” Davies said.

“This in itself has resulted in complacency in many commodity exporting countries because if you had China growing at 7 or 8 per cent, you don’t need to struggle.

“Unfortunately,” Davies said, “the world has changed. China is becoming more services driven, [so] countries now have to work hard to grow. The ones able to wean off this commodity-driven model will succeed”.

Charles Robertson, Renaissance Capital’s global chief economist who is an emerging-markets specialist, calls the US-China trade war a double-edged sword for African countries.

On the one hand, countries that sell hard commodities like oil, cobalt, copper or iron ore, including Angola, Zambia, Congo, Sudan and Nigeria, will be hurt, Robertson said, adding the countries’ currencies may be pressured to weaken.

On the other hand, he said, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Uganda and Rwanda – sellers of soft commodities such as tea, cocoa and coffee, as well as of gold, which has reached its highest price level in six years – may benefit from the trade war.

“Their external borrowing costs go down,” Robertson said. “The yield on one Kenyan euro bond has fallen from 8.5 per cent to 5.2 per cent in the last few months.”

Development Reimagined, a Beijing-based consultancy building Africa-China links, said that in 2017, eight African countries exported more than half their products (minerals or otherwise) to China compared with other members of the group of 20 leading industrial countries.

The analysis of Africa-G20 trade also said the most exposed country was South Sudan, which – with 15 of its oil operators now under US sanctions – exported 95 per cent of its oil to China.

It was followed by the Republic of Congo (63 per cent), Angola (61 per cent), Eritrea (60 per cent), Zambia (58 per cent), the Democratic Republic of Congo (56 per cent), Gambia (54 per cent) and Guinea (51 per cent).

By contrast, no African country exported more than half its products to the US, Development Reimagined’s chief executive Hannah Ryder said. Djibouti was the biggest African exporter to the US, sending 45 per cent of its products to America.

“Thus, any impact from the trade war is likely to come in terms of changes from the China side, versus changes from the US side, as the US either does not demand these products at all or gets them from elsewhere in the world,” Ryder said.

Ryder said mineral exports are relatively small compared with China’s overall imports. South Africa accounts for 32 per cent of all African products exported to China in 2017.

She said oil and mineral-exporting African countries will be affected by China’s demand for their products as the trade war stretches on.

Generally, China’s ongoing economic slowdown will have the greatest impact on commodity exports, according to Jeremy Stevens, Standard Bank’s chief China economist, who is based in Beijing.

China is “relatively less focused” on Africa, amid the trade war, a slowdown in infrastructure [projects] and real estate investment and other matters, Stevens said.

He said although China will continue to be a constructive force in global commodity markets, it is incapable of continuing to consume 40 per cent of the world’s resources and account for 20 per cent of its GDP.

“Increasingly, China, instead of being a demand story driving commodity prices higher, China’s largest impact on raw materials (and prices) will come from supply adjustments,” Stevens said.

African countries, however, still could turn the trade tensions into an opportunity by improving their competitiveness and deepening intraregional integration, according to AfDB.

“One way is to take advantage of the dislocation and trade diversion caused by the tensions to become the new supplier of goods previously supplied, for example, by China to the United States,” AfDB economists said in their report.

“Capturing even a small portion of the dislocation from increasing trade protectionism could benefit Africa.”

A growing number of African countries including Kenya, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Namibia, South Africa and Botswana have lately signed deals to export agricultural products into China.

Kenya recently got the green light to export avocados, tea, cut flowers and vegetables into China.

Beijing is looking to countries such as Ethiopia as a source of soybeans after China slapped a retaliatory 25 per cent tariff on US soybeans last year.

Development Reimagined’s Ryder said China is looking to expand imports from other sources aside from the US and diversify its imports – so that it is not dependent on a few countries.

“That could be positive for African countries as a whole if they can ensure high-quality, reliable supplies of key products. On the other hand, if China’s economy experiences a slowdown (especially on the manufacturing side), demand for raw materials, in particular, will fall,” she said.

For countries like South Sudan, however, which have guaranteed offtake agreements with China, the price is fixed for their oil, making them more immune to a slowdown in the Chinese economy, Ryder said.