China needs market-driven interest rate system to help yuan become global currency: economists

Improvements to China’s financial market, such as a market-driven interest rate system, are needed to help the yuan’s continued push towards becoming a global currency, senior economists say.

Jin Zhongxia, a former director general of the People’s Bank of China’s Research Institute, who is now China’s executive director at the International Monetary Fund, told a forum on Wednesday that bold moves were needed so that the value of the yuan could move more freely.

There also needed to be a more open-minded approach regarding capital outflow, he told the forum, organised jointly by the National School of Development of Peking University and China Business News.

However, Beijing’s global plans for the yuan suffered a setback last year after market fears caused by a hefty depreciation in the value of the currency, massive capital transfers and a tightening of financial controls by officials to try to control the yuan’s value and halt the outflows.

Li Yang, a former deputy director of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the forum that last year’s exchange-rate turmoil involving the yuan“was rooted in a non-market-based interest-rate system at home”.

He said China had removed the minimum price level on lending rates and the upper limit on deposit rates, but the authorities had yet to work out unified and broadly accepted interest-rate benchmarks, he said at the forum.

He also said the measures to manage liquidity conditions were “redistribution instruments rather than market-decided adjustment”.

Efforts were needed to introduce market forces, which would reduce distortion and risks involving interest rates and increase a willingness among people abroad to hold yuan assets, he said.

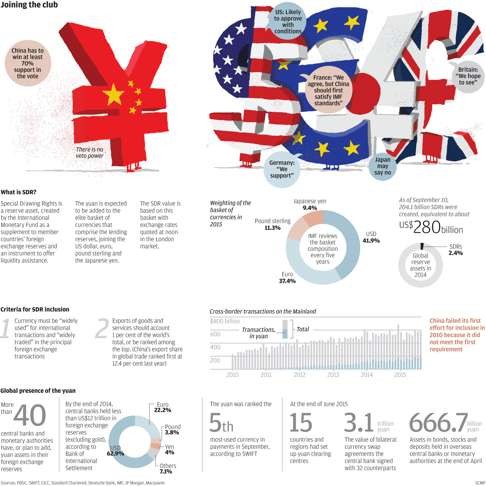

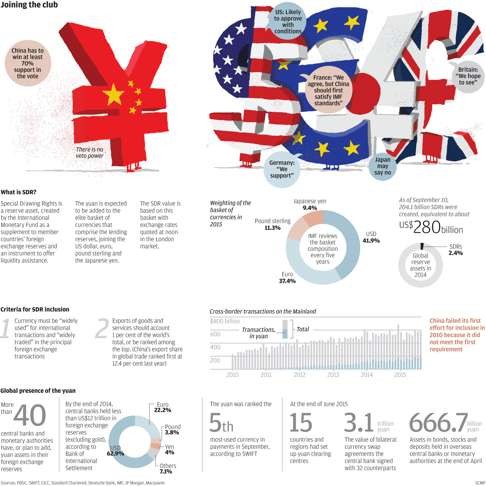

In December the International Monetary Fund’s Executive Board, which represents the fund’s 188 member nations, agreed to include the yuan as the fifth currency, along with the US dollar, euro, Japanese yen and pound sterling, making up its Special Drawing Right (SDR) – an international reserve asset that supplements the official reserves of its member countries.

Christine Lagarde, the IMF’s managing director, said in December: “The Executive Board’s decision to include the [yuan] in the SDR basket is an important milestone in the integration of the Chinese economy into the global financial system.

The [IMF] Executive Board’s decision to include the [yuan] ... is an important milestone in the integration of the Chinese economy into the global financial system. It is also a recognition of the progress that the Chinese authorities have made in the past years in reforming China’s monetary and financial systems

“It is also a recognition of the progress that the Chinese authorities have made in the past years in reforming China’s monetary and financial systems.”

Any change to the basket will take effect on October 1, with the yuan having a 10.92 per cent weighting in the basket, the IMF said.

Huang Yiping, a professor of economics at Peking University’s National School of Development, and a member of the People’s Bank of China’s (PBOC) Monetary Policy Committee, said it was important to address domestic problems in interest rates and financial defaults in order to reduce risks when opening a capital account.

“The direction of the yuan’s globalisation won’t change,” Huang said. “But a lot of work has to do at home when the yuan goes global.”

The PBOC, China’s central bank, ended its soft peg to the dollar last August 11, by devaluing the yuan nearly 3 per cent and reforming the yuan to fluctuate against a basket of currencies.

However, the panicked reaction of the market, amid a hefty deprecation in the yuan, forced the central bank back into a de facto peg to the dollar.

Later concerns about an economic slowdown in China and expectations about the US Federal Reserve introducing interest rates exacerbated capital outflows from the mainland and triggered an offshore depreciation in the yuan.

The central bank intervened heavily in the offshore market to defend the currency, such as draining offshore yuan levels and tightening outflows.

Jin said a change of mindset was needed regarding capital transfers out of the mainland. “There is no need to be too sensitive about outflows,” he said.

“Fear is caused by the lack of understanding – not just among ourselves, but others as well,” he said.

He cited the experiences in Russia, Brazil and India, adding that “the best way to manage capital outflow is to allow a flexible exchange rate”.

China has the instruments to manage the exchange rate and interest rate, and that is one important consideration for the IMF to include the yuan in its Special Drawing Right’s currency basket

“China has the instruments to manage the exchange rate and interest rate, and that is one important consideration for the IMF to include the yuan in its Special Drawing Right’s currency basket.”

Premier Li Keqiang reiterated this week that China was not intending to launch a currency war and was able to keep a stable yuan at a “reasonable and balanced” level. But there may be a few clues about how the central bank will do this.

Ma Jun, chief economist at the central bank’s research bureau, said the PBOC might allow the yuan to depreciate or appreciate against the basket of currencies over the long run while reducing short-term volatility.

Jin called for a full assessment of China’s current exchange rate policy, at a time when its counterparts in the eurozone and Japan had adopted a policy of negative interest rates to shore up their economies. Such policies had weakened the euro and Japanese yen, which had, therefore, pushed up the strngth of the yuan.

He said that in the past China had kept its promise not to devalue the yuan to show its support for the region during the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 and 1998, but that China had then suffered severe deflation in later years and struggled with pressure for reforms and massive lay-offs.

“That was connected to exchange rate policy,” Jin said.

Currently, deflation in China’s producer price index (PPI) – measuring the average change in selling prices of domestic producers of goods and services – has last 51 consecutive months.

Along with the high debt burden, the negative PPI has pushed up the real interest rate for enterprises, which will face more difficulties during the country’s efforts at deleveraging.