How China’s billion savers embarked on a household debt binge

With property the only reliable investment channel, leverage and risk are growing

Bonnie Cao, a PR worker for an investment company, used to be a typical Chinese saver, putting half her monthly income into a bank deposit account.

But that all changed at the start of this year when Cao and her army officer husband decided to buy a flat in Beijing.

The studio flat in downtown Beijing emptied the couple’s 400,000 yuan (US$59,000) life savings and they also incurred a debt of 1.35 million yuan to parents, colleagues and classmates to muster the remainder of the 35 per cent down payment. The rest of the purchase was financed by bank loans, with monthly mortgage repayments of about 20,000 yuan for 30 years.

But Cao said she felt lucky they bought their own flat in the Chinese capital because just a few days after their deal was completed, the city government imposed more restrictions on property purchases.

“Home prices rose so scarily in the past year that we are afraid we could never afford a unit in Beijing,” the 30-year-old said, explaining their decision to take on so much debt.

Hundreds of millions of Chinese households like Cao and her husband have fundamentally changed China’s economic and financial landscape over the past decade. The rising wealth of urban residents, based upon an almost uninterrupted property boom, and the growing debt levels in Chinese households are also set to shift the global economic balance.

Shortly after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 brought the global financial crisis to a peak, US economists including Harvard professor Kenneth Rogoff began to ask how things had gone so wrong. A key finding was that emerging markets, led by China, had “saved too much”, making it possible for the United States to borrow cheaply.

That was contested by the Chinese government, which argued there were historical and cultural reasons for China’s high savings rate. In a speech in 2009, central bank governor Zhou Xiaochuan said Chinese “valued thrift” and opposed extravagance, and that Chinese families had to save a lot because the health care and pension systems were underdeveloped.

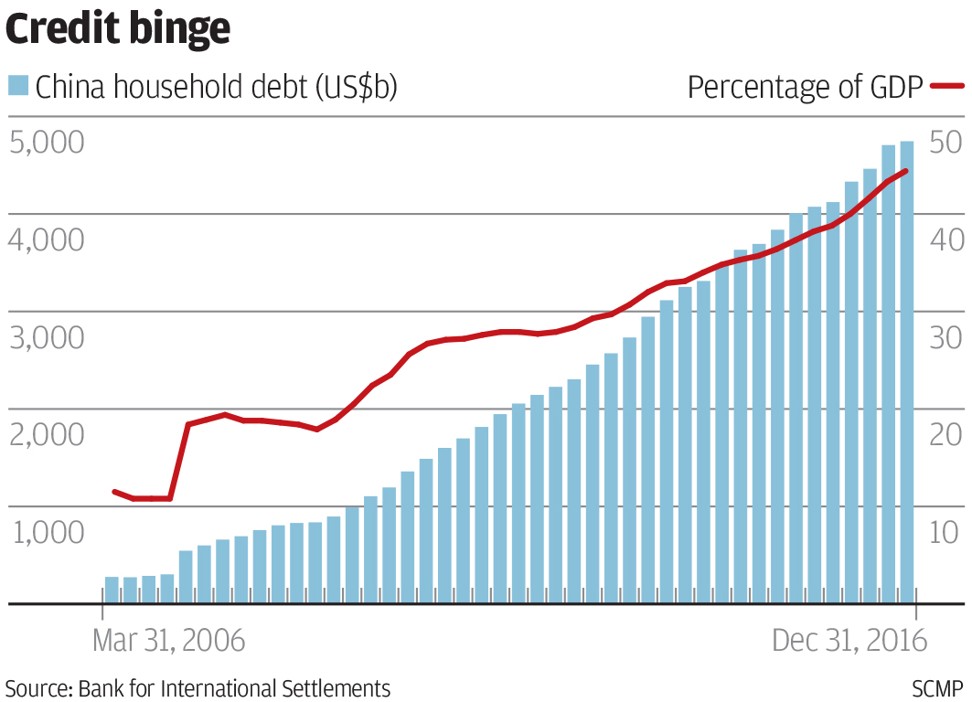

Since then, however, China’s massive money supply, urbanisation and a mortgage loan boom have resulted in a hefty rise in household debt, which is now equivalent to 44.4 per cent of national gross domestic product, triple the level in 2008, according to the Bank for International Settlements.

The net savings of Chinese households, defined as total outstanding deposits minus total outstanding loans, have stagnated or even begun to fall, showing that Chinese people are saving less and borrowing more.

Although China’s household debt level is still low compared to the 79.5 per cent of GDP in the US and 62.5 per cent in Japan, it has risen too steeply to be safe, according to a research report by the Institute for Advanced Research at Shanghai University of Finance and Economics which was published last month and led by former central bank statistics chief Sheng Songcheng.

“The speed of China’s household debt accumulation ... has exceeded that of US household debt accumulation before the subprime crisis,” it said, warning that the rapid growth would squeeze consumer spending and might lead to dangerous scenarios.

“As early as in 2020, the ratio of mortgage payments and disposable incomes in China will match the peak level in the US before the financial crisis,” it concluded, adding that the rising debt burden would “restrict China’s economic growth to some extent”.

Cao and her husband are rich on paper: their flat is now worth more than 5 million yuan, but they still live in a frugal life. They’ve let the flat out 6,000 yuan a month and she lived with her husband at his army quarters. To make sure they can repay their debts and make ends meet, she has minimised discretionary spending on restaurant meals, clothing and travel.

The impact of rising household debt has been most obvious in China’s major, tier-one cities, where property prices are chasing those in Hong Kong, London and New York. Uniqlo, a mass-market Japanese casual wear brand, is now a favourite of middle class Chinese, who also shop online in search of bargains.

Meanwhile, property has become the only reliable investment channel in China.

“Property has become a de facto carrier of wealth in China ... and the ultimate choice for investors given its high return in the past decades,” said Jin Li, deputy dean of Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management.

That’s lifted China’s rate of private property ownership to 89.68 per cent according to a survey by Chengdu’s Southwestern University of Finance and Economics – among the highest in the world and up from close to zero two decades ago. By way of comparison the rate in the US is only 65 per cent and that in Japan just 60 per cent.

More than half of Chinese family wealth is now held in the form of property and, according to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, residential mortgages comprise 60.3 per cent of household debt.

The rapid rise of leverage and household debt has sparked concerns China could be galloping down the same road to ruin followed by Japan in the early 1990s and the US in 2008.

President Xi Jinping warned against property speculation late last year, telling hundreds of economic officials at an annual work conference: “properties are for living, rather than speculation.”

Lu Zhe, a macroeconomic analyst at Tianfeng Securities, said the situation in China was “quite similar” to that in the US in 2004-2005, when signs of an impending crisis were beginning to emerge.

The property loan to value ratio had reached 50 per cent by the end of last year, he said, approaching the pre-crisis level of American households. That meant any substantial correction of home prices would have a catastrophic impact on household wealth and the banking system.

Tianfeng Securities estimates the mortgage instalment to monthly income ratio, a measure of borrowers’ repayment capability, has reached 67 per cent, well over the 50 per cent red line set by the banking regulator.

But Beijing will find it a challenge to defuse the debt bomb without upsetting homeowners.

“Property prices cannot and shall not collapse. That’s my guess or my best wish,” Cao said. “Government must jump to the rescue if that really happens. After all, it’s such an important part of government revenue and the national economy.”