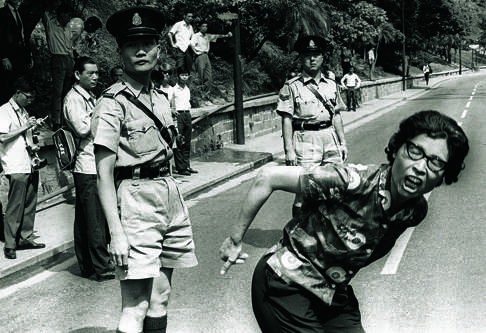

When the Cultural Revolution spilled over into riots in Hong Kong – and changed lives forever

A labour dispute at an artificial flower factory in San Po Kong triggered riots which claimed 51 lives, 15 through bomb attacks on the streets

Shortly after the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution in May 1966, some junior cadres at the Hong Kong branch of the Xinhua News Agency posted “big-character posters” inside the office and vowed to launch the Cultural Revolution within the branch.

Then Chinese premier Zhou Enlai emphasised that the practice of the Cultural Revolution would not be copied in the city, so the news agency’s leader in Hong Kong then looked for opportunities to instigate an anti-British struggle.

After the left wing in Macau claimed victory in the struggle against the colonial government in the then Portuguese enclave in December 1966, members of leftist organisations in Hong Kong went to learn from the experience.

Ho Ming-sze, an official with the United Front Work Department in Xinhua’s Hong Kong branch at the time, also went to Macau to learn from the “struggle experience”.

“Xinhua officials became restless after returning from Macau,” he said.

Ho, now 94, was promoted to head of the United Front Work Department at Xinhua’s Hong Kong branch in 1978 and retired in 1988.

The incident escalated quickly after the leftist camp and mainland officials stationed in Hong Kong seized the opportunity to mobilise their followers to protest against the colonial government.

The left wing was inspired by Beijing’s support for the “anti-British struggle” and called a general strike at the end of June, but the colonial administration stood firm against attempts to topple it.

The stand-off escalated when extremists planted bombs on the streets. The situation only calmed down in December 1967, when premier Zhou Enlai expressed Beijing’s official disapproval. By then the riots had claimed 51 lives, 15 in bomb attacks.

He joined a strike organised by the Anti-British Struggle Committee, founded by the leftist camp, which caused him to lose his lucrative job and be detained for 13 months at Victoria Road Detention Centre. Some 52 leaders of leftist organisations, including Lau, were detained at the centre during the riots, many for more than a year without trial.

On his release, Lau, now 87, held odd jobs such as truck driver. He said he felt abandoned by the leftist camp after the riots. Lau managed to acquire professional qualifications after working as a manual labourer for many years.

“Some rank-and-file members in leftist organisations were killed during the disturbances because of the false instructions from leaders of those organisations, who called on their followers to defend the premises of unions and schools at all costs,” he said.

“Their deaths could have been avoided if their leaders ordered retreats from the premises,” Lau said.

He was a Form Five pupil at the pro-Beijing Heung To Middle School in Kowloon Tong when he and 51 schoolmates were arrested on their way home from school on November 1, 1967.

They were stopped by a team of police officers near Somerset Road and were arrested for attending an unlawful and “intimidating” assembly in a public place under the emergency law in force at the time. Three of them had rejected police demands to search their schoolbags.

“We were arrested just because we were students from a left-wing school ... A month later, we were taken to the court without lawyers representing us,” Tsang said.

He was sentenced to a year in jail for attending an unlawful assembly. Another 20 schoolmates and the teacher were given jail terms from 12 to 20 months. In August 1968, his school threw him a welcome party when he was released.

But Tsang could not get a job as a schoolteacher after graduating from Baptist College, now Baptist University. He later found work as a nursing teacher and worked in nursing for the rest of his career, retiring as a manager at the North District Hospital in 2011.

Tsang, now 65, said he hoped Beijing could recognise what they had done in 1967.

“But our alma mater seldom mentioned what happened to us in the past decades,” he said.

Zhang asked a senior official from the liaison office to meet Tsang after the former student wrote to him to appreciate his recognition of what they did 49 years ago.

Beijing has seldom mentioned the 1967 riots in the past few decades, because of its disapproval of the disturbances, and because the riots reinforced the anti-Communist mentality among some Hongkongers.

Ho, who quit the Communist Party in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, lamented that Beijing had still failed to win the hearts and minds of many Hongkongers because at times the political movements launched by the Communist Party scared them off.